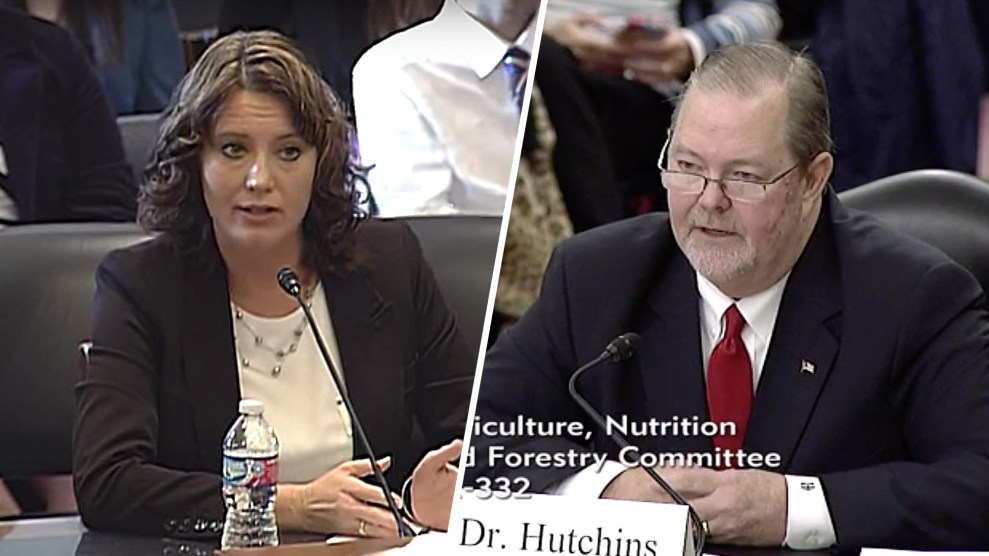

Mindy Brashears and Scott HutchinsagriAgriculture.senate.gov; YouTube

A presidential administration already shot through with corporate execs, lobbyists, and retainers just got two more.

On Tuesday, US Agriculture Department chief Sonny Perdue appointed Scott Hutchins, who once directed global pesticide R&D for Dow AgroSciences (now Corteva), as the department’s deputy undersecretary for research, education, and economics, and named Mindy Brashears, a Texas Tech professor who, over the last six years, has earned $320,000 in income from consulting and research work for the meat industry, as deputy undersecretary for food safety.

In the same announcement, Perdue named Naomi Earp as deputy assistant secretary for the USDA’s civil rights division.

Perdue’s decision to directly appoint the three to deputy posts—without Senate confirmation—was a highly unusual move. Each of them had been nominated to undersecretary posts last year, roles that would have put them in charge of important agencies within USDA. But such management positions require confirmation in the Senate, and all three saw their appointments languish without a vote before the 115th Congress ended.

Perdue’s fix: give them non-management job titles, which allow them to work within the USDA without gaining Senate approval. “In their deputy roles as selected by Perdue, they will not be serving in ‘acting’ capacities for the positions for which they have been nominated,” the USDA wrote in a statement. “As a result, they will not be able to exercise the functions or powers expressly delegated to the Senate-confirmed positions.” They have all been re-nominated to the full positions, but no date for a vote has been set. They started working in their deputy roles on January 29.

Here’s what to know about them:

Scott Hutchins: The undersecretary for research, education, and economics is also known as the department’s chief scientist. Back in 2017, President Donald Trump made a mockery of the title when he tried to hand it to Sam Clovis, a former right-wing radio host and business professor with no scientific credentials. Clovis ultimately withdrew his nomination over revelations that he played a role in the Russia scandal while working as an operative for the Trump campaign.

Hutchins, by contrast, holds a Ph.D. in entomology from Iowa State University, where he graduated in 1987. He joined Dow AgroSciences soon after, which later morphed into Corteva after Dow’s merger with DuPont.

So Hutchins is a scientist, at least. But his nomination is the latest step in what has emerged as a remarkably active relationship between Team Trump and the company formerly known as Dow Chemical. Months before its merger won the approval of US antitrust authorities, Dow donated $1 million to Trump’s inaugural committee. And Hutchins is the third former player from Dow Chemical’s pesticide/seed division to hold a high post in Trump’s USDA. Back in April, the administration tapped Ken Isley, a 30-year Dow AgroSciences/Corteva veteran, to lead the USDA’s Foreign Agricultural Service. In October 2017, another former Dow man, Ted McKinney, was confirmed by the Senate as undersecretary for trade and foreign agricultural affairs. McKinney had served for 19 years on Dow AgroSciences’ “US Food chain & state government relations” (read: lobbying) team.

More on Hutchins here.

Mindy Brashears: If the Senate confirms her to the undersecretary for food safety title, Brashears will oversee the Food Safety and Inspection Service, which operates a staff of 7,800 inspectors in more than 6,200 slaughterhouses nationwide. She is a professor at Texas Tech University, where she directs the International Center for Food Industry Excellence.

Brashears brought in at least $320,000 from five meat-related companies for research and consulting work between 2013 and 2018, the Texas Observer‘s Christopher Collins reported in September, citing ethics documents he obtained from Texas Tech. Clients included meat giant Cargill, pharmaceutical behemoth Merck, and chicken titan Perdue Farms. She gained national attention when she served as the star witness for South Dakota meat processor Beef Products Inc. in its “pink slime” defamation suit against ABC News in 2017, Collins reports. “BPI paid Brashears $100,000 to testify and to run tests on its products at a Texas Tech laboratory,” he wrote.

Naomi Earp: The USDA’s civil rights division sits on fraught ground. As historian Pete Daniel showed in his 2013 book, Dispossession: Discrimination Against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights, the USDA systematically discriminated against black farmers in the post-war years, often denying them loans and subsidies readily available to white farmers. In 2010, the USDA settled a long-standing discrimination suit brought by black farmers for $1.5 billion, on top of a 1997 settlement that paid out $1 billion.

Earp, who is black, has a tangled history as an administrator in federal civil rights enforcement posts, as this 2002 NAACP report shows. She got her start in civil rights enforcement in the 1980s when she worked as an adviser to Clarence Thomas, then the chairman of the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, a post he was appointed to in 1982 by former President Ronald Reagan. In 1987, the New Food Economy‘s Nathan Rosenberg reports, Earp left the EEOC to take over the civil rights division of the USDA—the same post she’s up for now. Here’s Rosenberg on how it went:

According to a subsequent investigation conducted by the House Committee on Government Operations, as well as numerous reports and committee hearings, however, she merely presided over an office designed to give the appearance that USDA was addressing discrimination—as required by federal law—without actually doing so. Discrimination against minority farmers and employees continued unabated during her tenure at USDA.

After a two-year stint at the USDA, she then took over the civil rights office at the National Institutes of Health for a couple of years. In 2002, former President George W. Bush nominated her to be chair of the EEOC. The NAACP staunchly opposed the choice, issuing a blunt report about her treatment of employees in the federal government during her time at the USDA and the NIH.

“Senate Democrats successfully blocked Earp’s nomination to the EEOC” in response to the NAACP’s concerns, but Bush “appointed her vice chair in 2003 after the Democrats lost control of the Senate,” Rosenberg reports. “She later chaired the EEOC from 2006 to 2009.”

Last February, the Trump administration nominated her to be an assistant secretary of agriculture in charge of civil rights, calling her a “retired career civil servant with more than 20 years of experience in Federal equal opportunity policy.” At her confirmation hearing with the Senate Agriculture Committee in November, she generated controversy by seeming to downplay the issue of sexual harassment. In response to a question about complaints of widespread sexual misconduct at the USDA’s Forest Service division, Earp expressed the need to “triage” workplace sexual misconduct cases “in a way to separate sexual assault from the silliness that goes on as a part of harassment.”

Later in the same testimony, she walked back the “silliness” remark (see this video, starting at 1:05), stating, “I probably shouldn’t have described sexual harassment as ‘silliness,’ although it is on a continuum.”