Manny Crisostomo/Sacramento Bee/Zuma

About two years ago, Joel Leon, 23, was applying for a server position at a restaurant in Ventura, California. He was proud of his resume—he had previously worked his way up to assistant manager at a fast food restaurant—and he felt good about how the interview went. But as he waited on a bench outside, he heard the white man who interviewed after him get offered the job on the spot, despite being less qualified. “He had little to no experience, and he got the job,” Leon says. “I really needed that job.”

It wasn’t the first time something like this had happened. Leon, whose parents immigrated here from Mexico, moved from working in farm fields alongside his mom as a teen to working in all types of restaurants to help pay the bills. He hoped to snag a front-of-house job like serving because of the better wages and tips. But, “it was really hard for me to get into those positions,” he says. “I’ve only been offered dish washer and busser positions, which is really unfortunate.”

The restaurant industry is one of the largest and fastest growing private-sector employers in the country, and almost half of its workers are people of color. But as the industry continues to grow, its non-white workers continue to be underrepresented in higher paying positions.

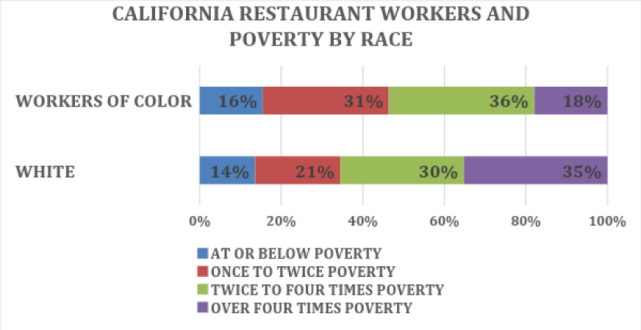

This trend is all too apparent in California, where restaurants employ nearly 1.6 million workers, or just over 9 percent of the state’s workforce. According to data compiled by researchers at the advocacy group Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) United and the racial justice nonprofit Race Forward, even though workers of color make up more than 70 percent of California’s restaurant workforce, fewer than 18 percent of them make $31 dollars an hour or more, or four times the poverty level (what ROC considers a living wage in the state), compared to 35 percent of white restaurant workers.

Poverty by race among restaurant workers in California (Data from: American Community Survey, 2013-2017).

In the culinary hub of the Bay Area, where the restaurant industry employs more than 300,000 of the area’s 3.5 million people, 45 percent of white restaurant workers make a living wage as servers, while only 28 percent of workers of color do. At the national level, those percentages are 22 percent and 19 percent, respectively. The Bay Area’s fine dining restaurants, which offer patrons their pick of sophisticated cuisine from India, Morocco, and Japan, sometimes within a one-block radius, pay white workers six dollars more an hour, on average, than workers of color.

“We are diverse but not equitable,” ROC United president Saru Jayaraman said at a press conference for the release of the group’s new report on racial equity in the Bay Area’s restaurant industry.

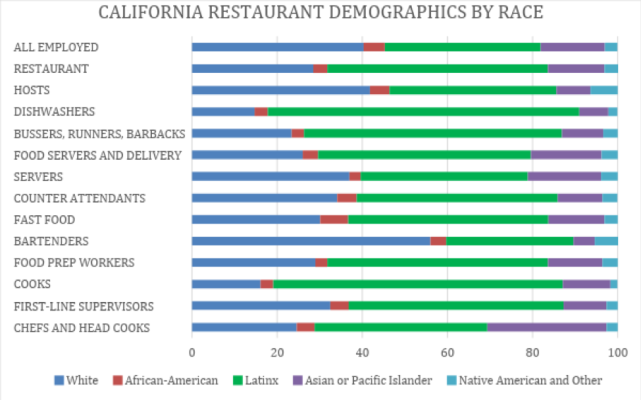

The reason for the imbalance is in part due to the fact that workers of color are concentrated in fast food or family style restaurants and lower paying restaurants positions, and in the back-of-house (or kitchen). People of color make up about 85 percent of dishwashers and more than 75 percent of runners, bussers, and barbacks in California, according to information pulled from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. By comparison, they are underrepresented in higher paying and more visible positions, accounting for under 45 percent of bartenders.

Demographics of the restaurant workforce by race in California (Data from: American Community Survey, 2013-2017).

Daniel Patterson, an award-winning San Francisco-based chef whose restaurants include the two-Michelin star Coi and several others in his Alta Restaurant Group portfolio, didn’t used to spend too much time focused on the racial makeup of his staff. But that changed about eight years ago after he started a nonprofit geared towards teaching resource-strapped young people cooking skills. The experience sparked “an awareness of responsibility,” Patterson told Mother Jones.

In 2017, Patterson and his team signed up for a pilot program developed by ROC United and Race Forward to reduce implicit bias and improve racial equity in Bay Area restaurants. They agreed to look under the hood of hiring practices and staff diversity at his restaurant Alta, a casual fine dining spot in San Francisco that has now re-opened as Kaya. The initial evaluation revealed some startling truths. Ninety-two percent of Alta’s white employees had front-of-house positions (85 percent of whom were in top-tier positions like servers, maitre’d, and bartenders), compared with 31 percent of its employees of color. Conversely, while almost 40 percent of the restaurant’s minority workers occupied lower-tier kitchen jobs like prep cooking or washing dishes, only 8 percent of the white workers had these types of roles. “We were like ‘Wow—it’s worse than we thought it was,'” Patterson says.

Ninety-two percent of Alta’s white employees had front-of-house positions, compared with 31 percent of its employees of color.

While undergoing an implicit bias training, even staff members who had already been aware of the racial divides around them found that they had been susceptible to unconscious biases, and may have been helping to perpetuate them. “I was doing the things that led to segregation, and I’m a person of color,” says Gabriel Barba, Alta Group’s director of learning and development. “I’m an immigrant. I’m a gay person,” he adds. When Barba worked as a manager, and was hiring for new positions, for instance, he would usually ask current servers for referrals. That practice increased the likelihood that new hires would come from the same socioeconomic and racial—usually white—circles.

Through the pilot program, Alta’s management implemented a number of new practices. At the core of their transformation, Barba says, was standardizing the hiring, advancement, and training processes. Managers at all the Alta Group restaurants now stall the hiring process until they have a diverse pool of candidates for a position. And during interviews, they use the same questions and answer scoring system specially researched and developed to reduce bias. A similar process is used for all advancement evaluations.

“That one thing alone will allow the applicant to reveal themselves in a multi-faceted way and in the same way person to person so you can make better decisions about who to hire based on their actual character, skills, experience,” Patterson says. Post-intervention, the percentages of white employees and employees of color at Alta were much more evenly distributed. Eighty percent of white workers are still in front-of-house jobs, but now so are 62 percent of the restaurant’s workers of color (and 49 percent of them work in the higher-level dining room positions). Still, none of the lowest tier kitchen jobs were held by white workers by the end of the six-month pilot.

At the mac-and-cheese restaurant Homeroom in Oakland, which also went through pilot program, tools like racial equity training and requiring hiring teams to include people of color yielded similarly encouraging results. In the spring, ROC United partnered with the business school at University of California, Berkeley, to develop a paid online version of its training program.

But, especially in a tough industry with limited resources and slim margins, many restaurants won’t be able or willing to dedicate the time or money to the process Alta Group went through, despite the prospect of longer-term benefits like less turnover and higher staff satisfaction. “It can be challenging to change your work practices when you’re trying to meet your day-to-day operations,” says ROC’s Teófilo Reyes, the report’s author. Patterson is quick to acknowledge that few free-standing restaurants would develop these processes from scratch, but “could they take what we’ve already developed and implement them? I think the answer is yes,” he says. “Everyone wants to do things a little bit differently, but still, to have a starting point was our goal.” And asking job candidates the same questions takes minimal additional resources, he points out.

ROC and Race Forward advocates have been working with California legislators and the City of Oakland to encourage the adoption of legislative incentives to address segregation, like offering restaurants who are willing to engage with the issue tax breaks or expedited permits, licenses, and certifications. Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf signaled support for these measures during the report’s press conference on Tuesday.

“This is an industry that has roots in slavery, that has roots in systemic racism, and while we evolved, that history and those foundations are still impacting this huge industry today,” she said, noting that she’d witnessed racial segregation firsthand during her time spent bussing, waitressing, and hosting. “We would love to serve as a model and hopefully inspiration to other cities.” What steps Oakland will take remains to be seen.

Changing a restaurant’s structure isn’t easy, Alta Group’s Barba notes, but after the pilot program, workers at his restaurant are more satisfied now, meaning they are more likely to stick around. “It’s going to be challenging, but it’s going to be worth it,” he says. “Everyone should want non-segregated restaurants. It’s going to be a good thing not just for the employees, but for businesses.”