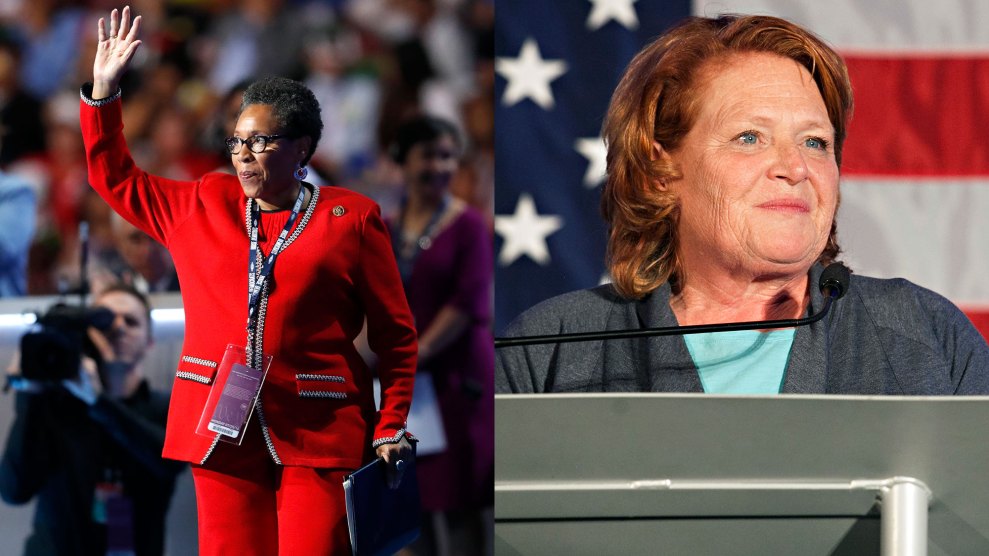

Ohio Rep. Marcia Fudge (left); former North Dakota Senator Heidi Heitkamp (right)Paul Sancya/AP; Ann Arbor Miller/AP

As the Biden-Harris transition pushes forward, without cooperation from the defeated incumbent, speculation is swirling over future leadership of the US Department of Agriculture, which executes food and farm policy. Sonny Perdue, the USDA secretary under President Donald Trump, made headlines during his tenure for showering cash on large-scale commodity farmers—disproportionately in his home state of Georgia—to buffer them from his boss’ trade wars; and for publicly pining to cut wages for migrant farm workers. President-elect Joe Biden’s pick for the next USDA chief will signal a lot about the kind of administration he seeks to run.

Various publications have released short lists for agriculture secretary that include Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), Rep. Cheri Bustos (D-Ill.), Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-Maine), and Karen Ross, secretary of the California Department of Food and Agriculture. But several sources tell me that the Biden team has narrowed the search to two leading contenders: former North Dakota Senator Heidi Heitkamp and Rep. Marcia Fudge (D-Ohio).

Last week, Politico called Heitkamp the “top pick” among Biden’s prospects. She champions the food policy status quo of supplying farmers with direct payments and subsidized crop insurance to convince them to maximize production of corn, soybeans, cotton and a few other commodities. She has the backing of Tom Vilsack, the dairy-industry executive who led the USDA during the Obama Administration, and who has emerged as Biden’s top informal adviser on rural and agriculture policy.

Heitkamp is tightly allied with her state’s massive oil and coal interests, and has consistently opposed action to cut greenhouse gas emissions to fight climate change. After losing her senate seat in the 2018 mid-terms, she launched the One Country Project, a group that tries to help the Democratic Party engage rural voters.

Heitkamp’s politics are so non-threatening to agribusiness interests that when Donald Trump was forming his cabinet after the 2016 election, he temporarily placed her at the top of the shortlist for his USDA pick, before ultimately settling on the pro-agribusiness stalwart Sonny Perdue, a Republican former governor of Georgia.

She’s thus a unicorn: the only person to be shortlisted for a top cabinet post in both the Trump and incoming Biden administrations.

Fudge, for her part, represents the majority-Black precincts of Cleveland, as well as parts of nearby Akron. If she gets the USDA nod from Biden, Fudge would be a kind of unicorn, too—the first urban-centered politician to lead the agency, as well as the first Black woman to take its reins.

In a Politico story published Nov. 11, Fudge declared her desire for the job—and made a case for herself that will be hard for Team Biden to ignore. “When you look at what African-American women did in particular in this election, you will see that a major part of the reason that this Biden-Harris team won was because of African-American women,” Fudge told the outlet, adding that she would not be satisfied with the cabinet post often reserved for Black politicians from cities: secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Like Heitkamp, Fudge has backers who have potent sway within Biden world. Democratic Majority Whip Jim Clyburn (D-S.C.) helped save Biden’s campaign in early 2020 by backing him in the South Carolina Democratic primary, helping propel him to the nomination. “Clyburn has spoken to the Biden camp about a Fudge USDA post, according to an aide,” Politico reported. The Congressional Black Caucus has also rallied around the pick—a potent endorsement, given what the president-elect told Black voters at his victory speech on Nov. 7: “You’ve always had my back, and I’ll have yours.”

Fudge has strong food-policy chops—she’s a longtime member of the House Agriculture Committee, and chairs its Nutrition, Oversight, and Department Operations Subcommittee, which oversees anti-hunger programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as food stamps) as well as USDA operations. She has been a fountain of policy proposals to defend front-line food workers and fight hunger during the pandemic. She co-sponsored a bill that would stop the USDA from allowing meat companies to speed up slaughterhouse kill lines, a factor in the extraordinary burden COVID-19 has placed on the industry’s workers; and another that would make school lunches free to all students during the pandemic.

Meanwhile, several grassroots farm, environmental, and anti-hunger groups have risen to support Fudge. “First of all, it’s time for an individual of color to lead the USDA,” said Joe Maxwell, executive director of Family Farm Action, citing the agency’s lavishly documented history of discrimination against Black farmers. Since the USDA’s founding under President Abraham Lincoln, only one Black person, Mississippi politician Mike Espy, has led the agency, a post he held for one year.

Even the Obama USDA left a checkered legacy on race. Vilsack infamously fired the veteran Georgia farmer and civil rights leader Shirley Sherrod from an appointed USDA post after the right-wing website Breitbart released doctored footage falsely portraying Sherrod as lashing out at white people. Vilsack ultimately apologized for the episode. And a 2019 investigation by the food-news site the Counter found that while the Obama-era USDA “came to enjoy a reputation among policymakers and the press as a steady force for good in the lives of historically marginalized farmers, Vilsack and others in the department made cosmetic changes, and little else.”

As a result, Maxwell said, “there’s still a cloud hanging over the USDA on race, and Fudge is perfectly qualified to make long-overdue progress on that front—as well as move the agency forward in other areas as well,” including preparing farmers for climate change and reducing the power of agribusiness companies exert over them. Family Farm Action is part of coalition of 16 groups—including Friends of the Earth, the Humane Society of the United States, and the Open Markets Institute—who have endorsed Fudge’s bid to be USDA secretary.

Those groups were among 160 sustainable-farming, food justice, and environmental organizations to sign a scathing Nov. 17 letter to the Biden transition opposing Heitkamp as the next USDA chief. “Tapping Heitkamp for this position in the Biden Administration would enable the continuation of disastrous Trump-era food and farm policies, jeopardize President-Elect Biden’s climate goals, and boost corporate agribusiness at the expense of family farmers, frontline communities, the environment, hungry families, and animal welfare,” the letter stated.

Early in his campaign for president, Biden presented himself as a restoration candidate—he promised to wipe away the stain of Trumpism and revive the status quo he helped establish in the Obama era. Then came 2020, with its oft-resurgent pandemic, the related economic and hunger crises, and a barrage of climate-related catastrophes, from California’s fires to hurricanes lashing the Gulf and East coasts. Biden won the Democratic nomination and ultimately the presidency after refashioning himself as transformational figure with an ambitious agenda for confronting the mounting challenges we face.

But Heitkamp’s emergence soon after the election as the favorite for the position hints that Biden remains pulled to the centrist, corporate-friendly policies that have characterized his whole career. Whereas choosing Fudge would show an openness to making good on the transformational promises that propelled him to the job he has coveted for decades.