Mother Jones illustration

Cooking helps keep me sane, so the lockdowns and restaurant closures of early spring didn’t shake up my food routine that much. Like millions of others, my household stocked up on pantry staples, less out of a hoarding impulse than to minimize shopping trips. Otherwise, we got busy in the kitchen, more or less like we always do.

But as the pandemic dragged on for months with no end in sight, the longing for restaurants—not fully salved by occasional takeout—began to grind on me, as did the vanishing of dinner parties. The tedium of daily cooking began to overwhelm the pleasure. In her recent essay on pandemic-induced kitchen fatigue, The New Yorker’s Helen Rosner captured my exhaustion. The phrase “I love cooking,” she wrote, emerged as a mantra she has to chant when “I clatter around in the cabinets in search of whatever skillet is inevitably at the very bottom of a teetering stack of pans, or ram the blade of a knife through the stalks of yet another head of celery, or fling a handful of salt resentfully at a wholly blameless chicken.” Rosner didn’t mention another associated curse: the stream of dirty dishes.

On top of the merciless repetition of tasks, my go-to kitchen moves, built up over decades, became a burden. Dishes that once reliably excited my palate suddenly became dull. The kitchen began to lose its status as a haven from the stresses of existence; the awfulness of 2020 had seeped in. I needed to shake things up, move in new directions, find ways to rebalance the ratio of drudgery to joy delivered by hands-on food preparation.

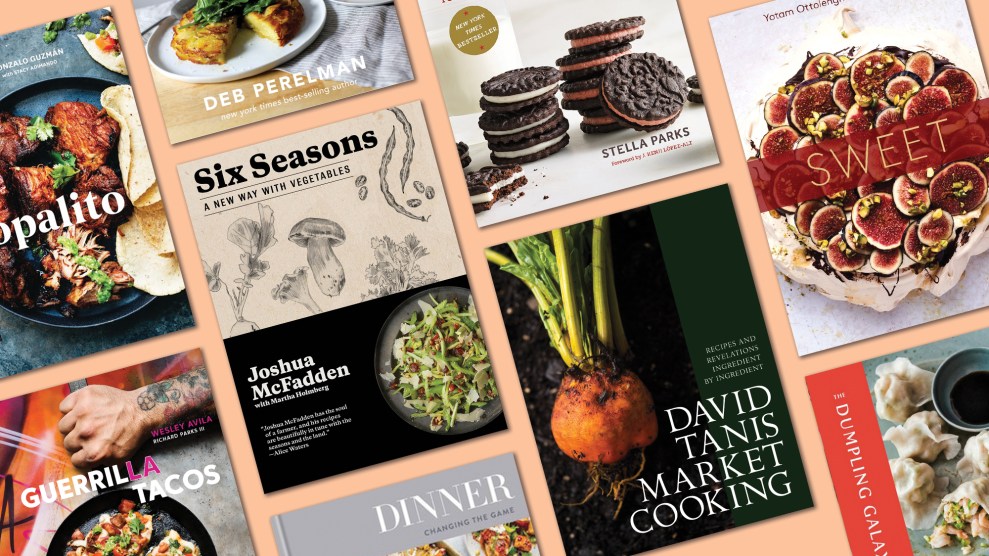

Here are some cookbooks and online ingredient shops—plus a food-media company—that helped knock me out of old ruts and re-enchant the kitchen, when I needed its consolations most.

Land of Plenty: A Treasury of Authentic Sichuan Cooking

I love Sichuan cuisine, with its emphasis on fresh vegetables, chili-pepper heat, and the tongue-tingling peppercorns that bear the region’s name (which are actually the seeds of a shrub in the citrus family). But for a long time, I only ever consumed it in restaurants. Land of Plenty (first published in 2003), by Fuchsia Dunlop, sat idle on my bookshelf for about a decade, as I failed to stock up on the pantry items required to cook these complex dishes. Early in the pandemic, I interviewed the chef/recipe developer J. Kenji López-Alt—author of The Food Lab cookbook—and he mentioned a classic Sichuanese dish called mapo tofu as a favorite quick family meal. That set off a powerful memory of enjoying mapo tofu in Manhattan’s Chinatown many years before, and an equally powerful craving for it. Mapo tofu emerged as a new weekly dish in our household. And it inspired me to open Dunlop’s masterpiece and dig in, conjuring up dishes that tasted nothing like anything that had previously emerged from my kitchen: loaded with umami and the deep, sour flavor of Shaoxing, the region’s famed rice wine. I don’t regret putting off my dive into Sichuan cooking for so long: in a sense, I had been saving it for the right time.

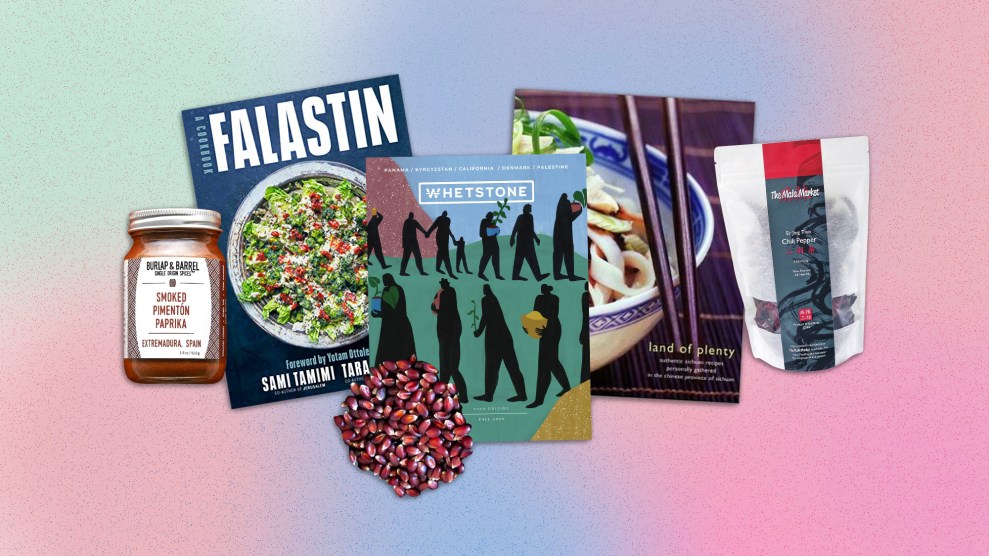

Mala Market

When you dig into the English-language Sichuan-cuisine internet, you quickly find references to Mala Market, an online retailer devoted to importing top-quality condiments straight from Chengdu and surrounding territory. The stuff I’ve been ordering from Mala has enlivened my cooking, and not just my forays into Sichuan fare. Pixian, also known as Doubanjiang, is a kind of mother sauce of the region’s food. A paste of fermented fava beans and fiery-hot chilis, it’s what gives mapo tofu its ineffable punch. It’s also shortcut for adding umami and fire to non-Sichuan dishes. I’ve stirred a lump of it into a pan sauce after searing steaks, and enriched a marinade for roasted chicken with it. Once, in a fit of Doubanjiang obsession, I melted some with butter and used it to dress popcorn. (It was really good.) Mala offers two grades, both of which I keep on hand: an everyday one and and a deluxe aged version. Other Mala gems: delicate, additive-free soy sauce; Chinese sesame paste (a darker, denser version of tahini, and a staple of Sichuan cooking), and a variety of dried chili peppers, which have sparked joy for me in the form of home-made chili oil and chili crisp.

Vietnamese Food Any Day: Simple Recipes for True, Fresh Flavors

Vietnamese is another beloved restaurant cuisine I had never focused heavily on in the home kitchen. Andrea Nguyen’s Vietnamese Food Any Day has been sitting on my shelf since it came out late last year. During the pandemic, I dug in. At its heart lies something central to the pandemic experience: food shopping. In the introduction, she teases out the “seeds of my supermarket obsession.” As a child in Saigon, she experienced an open-air market, “huge and noisy, with vendors hawking dry goods, vibrant produce, freshly butchered meats, and live seafood.” Not long after, in 1975, her family fled Vietnam and alighted in Southern California. The accessible market there was an Albertson’s, where the family found a narrowed palate of choices, bereft of staples like fish sauce. They lived on “rice, cheap chicken backs, onion, ginger, and celery,” creating familiar dishes by turning granulated sugar into bittersweet caramel sauce, a Vietnamese staple, and leaning on La Choy soy sauce, an American brand. In the intervening years since her family’s first Albertson’s encounter, fish sauce (like the great Red Boat brand) and good soy sauce are now easily available in the United States, and Nguyen has delivered an excellent guide for people who want to work Vietnam’s irresistible flavors into simple home cooking. Her roast chicken noodle soup is as healing as it sounds: a concoction of chicken, ginger, mushrooms, noodles (any kind), greens, and herbs (whatever’s on hand). I cooked through every part of the book. Her recipes are precise, flexible, and beautifully written. Nguyen repeatedly pulled my household out of pandemic malaise, and enticed us to put something fun and delicious on the table. This book has earned its place on our small shelf of everyday cookbooks.

Falastin: A Cookbook

Falastin, by Sami Tamimi and Tara Wigley, is an ode to the cooking of Palestine, combined with a clear-eyed, soulful travelogue. I cooked from it a bunch in preparation for my interview with Tamimi, a Palestinian-born chef and a leading light in London’s Ottolenghi cookbook and restaurant dynasty. His silky hummus, used not as a dip but rather as a backdrop for other savory delights like meatballs and fried eggplant, has become a household staple—even sometimes for breakfast, like they do it in Palestine. The book brims with new ways to dress up standbys like eggplant, turnips, and squash (both summer and winter), always served under a riot of chopped herbs and perked up with tart additions like lemon juice and sumac. And the book added a dead-easy, addictive condiment to my repertoire: sour, fiery-hot shatta (recipe at the bottom of this piece.)

Burlap & Barrel

I’d been hearing for a while from people in foodie circles that there was an enterprise that procures dried herbs and spices the way some roasters buy coffee beans—from small producers or co-ops paid a fair price for high quality. But I was stuck in the world of placeless commodity spices bought in bulk from my local natural food store. Then someone on Twitter mentioned Burlap & Barrel’s za’atar, the classic Palestinian herb-spice mix (wild thyme, oregano, sesame seeds, sumac, sea salt). I couldn’t resist ordering a jar, sourced from a women’s cooperative in Occupied Palestine. Bright, earthy, and herbal all at once, the za’atar (and its origin in Palestine) helped bring Tamimi’s recipes and stories to life on my plate. Since that initial order, I’ve gotten hooked on B&B’s wild mountain cumin (Afghanistan), smoked paprika (Spain), and Black Urfa chili (Turkey), and seasonally available dried ramps (northeastern United States). All add drama and zing to my standby dishes and point me in new directions. And all have found their way, at one time or another, onto…

Rancho Gordo Crimson Popping Corn

California-based Rancho Gordo is best known for its heirloom beans, celebrated by The New Yorker, CBS News, and me. Because they’ve emerged as a cult item during the pandemic, many varieties are currently sold out. But the company’s sublime popcorn remains available (as of mid-December) and it’s the best I’ve ever had. It pops into dense, crispy bombs of pure corn flavor, with a dark-crimson kernel at the center. The product shines with a classic dressing of melted butter, nutritional yeast, and salt; and moves toward the sublime when you add smoked paprika or za’atar or Doubanjiang. Sometimes, a big bowl of the stuff is just the right dinner.

Whetstone Magazine

Inspiration didn’t come only in the form of recipe books or ingredients. In early September, with the pandemic re-surging and election stress swirling, a fresh edition of Whetstone arrived in the mail. Lovingly produced on thick paper stock with gorgeous photos, the issue offers a series of vignettes from around the globe featuring people using food to make meaning in a world torn by colonialism and racism.

A piece by Ishay Govender takes us into the culinary heart of the African diaspora in Lisbon—metropole of the former Portuguese Empire, a major driver of the Atlantic slave trade, and a colonial force in Africa that violently clung to power there until the 1970s. Among the restaurateurs Govender profiles is Isabel Manuel Jacinto, a woman who was separated from her family as a two-year-old in Angola and brought to Portugal by a white military commander in 1965, amid the chaos of the Portuguese Colonial War. Jacinto, who grew up thinking her family abandoned her during the war, recently returned to Angola for the first time and found that her mother had never left her like Jacinto thought she had, but had instead died “from a broken heart” over her toddler daughter’s abduction.

Today, at her Lisbon restaurant Batata Doce, Jacinto offers “signature Angolan dishes like muamba de galinha (chicken and okra stew) with funge (dense cassava porridge).”

The issue also includes stories about the struggle to preserve the biodiversity of Mexico’s avocados from the forces of global capitalism; safeguarding Salvadoran foodways in Oakland; and on Philadelphia-born Palestinian Nader Muaddi’s quest to preserve the tradition of arak, “the world’s oldest spirit,” distilled from grapes and infused with anise.

In a July interview with Whetsone’s cofounder, Stephen Satterfield, I learned that his publication is currently the nation’s only Black-owned print food magazine, and that he had to fight to get it off the ground, amid serial rejections from white investors. Listen in here: