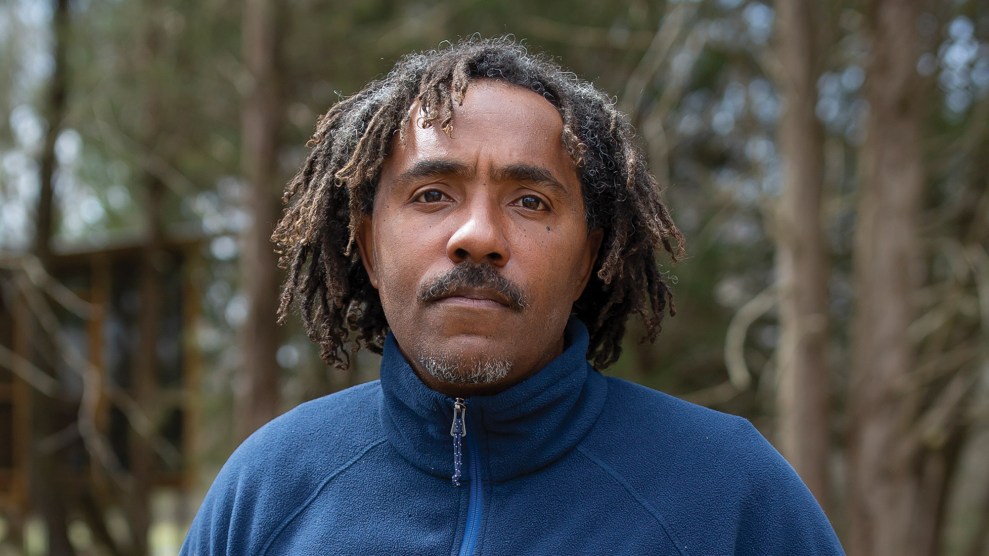

Tahz Walker stands on land that he and others own communally as part of Earthseed Land Collective in Durham, North Carolina on March 14, 2021. Walker and his partner Cristina Rivera-Chapman run Tierra Negra Farm which provides produce for farm shares as well as fresh vegetables to communities in downtown Durham.Madeline Gray

Agriculture was once a major source of wealth for Black American families. According to scholar Thomas Mitchell, by 1910, up to 80 percent of the Black middle and upper class owned farms. But over the course of a century, Black-owned farmland has diminished to the point of near extinction: Only 1.7 percent of farms were run by Black growers in 2017.

“We’re looking at about 98 percent of farmland ownership being in white hands today, and that’s more racially skewed than it’s ever been before,” Farming While Black author Leah Penniman told Bite podcast last year. “I think it says a lot about this nation, the fact that all the arable land is concentrated into the hands of one demographic group.”

The story of how that happened—from sharecropping, to anti-Black terrorism, to exclusionary USDA loans—is the focus of the latest episode of the Mother Jones Podcast. Tom Philpott, Mother Jones’ food and agriculture correspondent, joins Jamilah King on the show to talk about the racist history of Black farming and his recent cover story on a new movement to reclaim Black farmland.

Tahz Walker is part of a resurgent movement of Black farmers who are returning to the land. His farm cooperative, Tierra Negra, sits on land that was once part of a huge and notorious plantation in North Carolina called Stagville. Today, descendants of people who were enslaved at Stagville own shares in Tierra Negra and harvest food from there.

Walker is the descendant of sharecroppers, but for most of his life his father never talked about it because this was a piece of his family history that was laced with trauma. “They just weren’t able to own any land,” says Walker on the podcast. “The trauma of it gets passed down.”

Much of the farmland that was denied to Black farmers was transferred into white hands, and over the course of the 20th century, the price of farmland rose dramatically, leading to a loss of wealth that has been compounded by escalating real estate prices. Dania Francis, an economist at the University of Massachusetts Boston and a researcher with the Land Loss and Reparations Project, has calculated that the land that Black farmers lost between 1910 and 1970 is worth $300 billion today–and that’s a conservative estimate.

The value of farmland far exceeds the cost of the land, explained Francis. “There’s also the value it creates in being, for example, collateral. And the ability then to use that to finance education, finance the investment in other businesses or other ventures,” she explains. Losing access to those opportunities, she says, is part of why Black households today “have a median wealth of about $17,000, compared to white households, which have a median wealth of somewhere near $171,000. So almost tenfold.”

The campaign to reclaim Black farmland has received some political backing. Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ) introduced the Justice for Black Farmers Act in 2020, a bill that would attempt to reverse the discriminatory practices of the USDA by buying up farmland on the open market and giving it to Black farmers. The bill has received backing from high-profile on the left, including Senators Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Reverend Raphael Warnock (D-GA), though it is unlikely to get the votes it would need to override the filibuster and pass.

But the bill attempts to address a core issue at the heart of the loss of Black farmland: the Black-white wealth gap. When Tom asked Francis about how to redress the lost land, she answered without pause: “A direct way to address a wealth gap is to provide Black families with wealth.”