Open any page in Who Shot Rock & Roll? A Photographic History, 1955-Present, and you’re likely to run into a familiar face—if not an old friend: Bob Dylan, cigarette in mouth, walking keep-warm-close with a woman down a snow-covered street. John Lennon in sunglasses, arms folded across his New York City T-shirt. The Ramones in ripped jeans, lined-up against a grimy brick wall. Hendrix kneeling over his flaming guitar. Johnny Cash flipping off the camera at San Quentin.

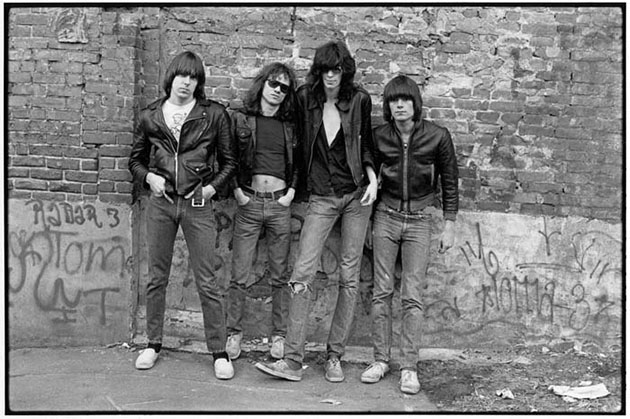

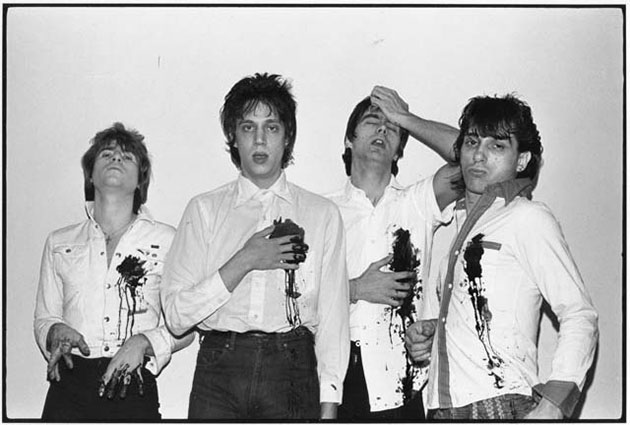

The Ramones (left to right: Johnny Ramone, Tommy Ramone, Joey Ramone, and DeeDee Ramone), New York City (1976) by Roberta Bayley

This photograph of the Ramones was used on their first album cover. It was originally shot for PUNK, the outrageous magazine edited by Legs McNeil and John Holstrom, with photographs by Bayley in each issue. This photo wasn’t supposed to be the cover for the Ramones’ first album. Their record company, Sire, had hired a professional photographer, but the group didn’t like the result. They had blown their photo budget and could pay Bayley only $124 for what has become the classic Ramones image.

From Who Shot Rock & Roll, by Gail Buckland

Gail Buckland’s new book introduces us to the photographers behind more than 200 iconic music photos, many of them already seared in our consciousness from the posters plastering our bedroom walls, album covers studied for hours, magazines thoroughly absorbed. These images, for better or worse, helped make us who we are.

Buckland champions the unsung hero in this part of our collective cultural cornerstone: the photographer. She tells the stories of the men and women who snapped the shots we’ve come to know so well. Some were budding photographers who happened to be in the right place at the right time. Others were artists working with photography and within music. And still others were hired hands, cranking out photos for record labels over the decades.

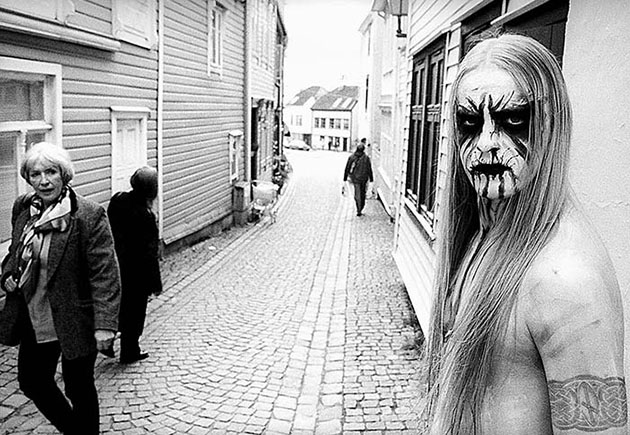

Kvitrafn of Wardruna, Bergen, Norway (2002) by Peter Beste

Photographer Peter Beste spent seven years photographing Norweigan black-metal musicians, men so extreme they have been accused of burning churches and committing murder. The musicians are visually exciting and, as Beste says, their concerts cannot be described in words. His photographs show Norweigan Black Metal’s deep connection with the forces of nature, Satanic ritual, Norse mythology and pagan religion.

Frank Zappa, “Himself,” New York City (1967) by Jerry Schatzberg

A wonderful straight portrait of a goofy, great rock-and-roll Dadaist. What perfect colors for the man whose final album would be called The Yellow Shark. What perfect colors considering Tom Wolfe’s The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streammline Baby was set, in part, in Jerry Schatzberg’s studio. The portrait doesn’t look into the soul of Zappa, it looks at what makes him unfathomable

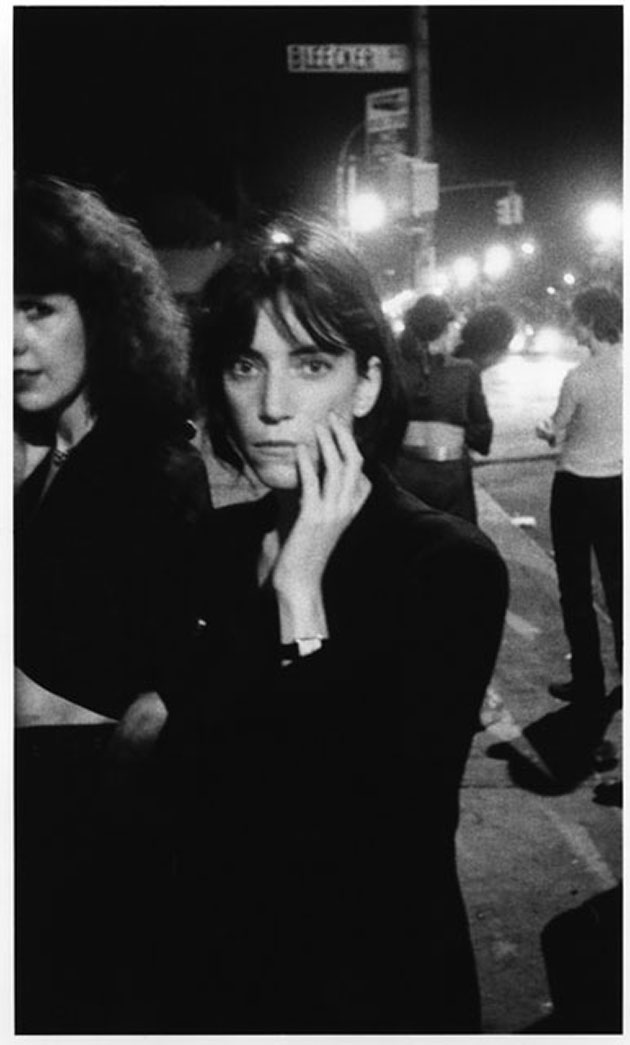

Patti Smith outside CBGB, Bowery and Bleecker Street, New York City (1976) by Godlis

Godlis was a young street photographer in New York. “I showed my photographs to [my art-school] friends who were very cutting edge. The snobbery of artists! They couldn’t even comment on it. How did he go [they wondered] from Winogrand and [Lee] Friedlander street photography to just making pictures of ‘musicians in a club?’ And then they said, ‘You are taking pictures of BAD musicians—the next level down.’ It wasn’t like taking pictures of good musicians like Miles Davis.”

The selection of images (and photographers) includes intimate, close-up portraits, backstage candids, private moments, and onstage antics by musicians you’ve no doubt heard of, shot by people you most likely haven’t. The book spans popular music from Buddy Holly and Elvis to the White Stripes to Puff Daddy and Jay-Z.

In certain circles, music photography is derided as mere “entertainment photography,” a step above shooting stills on a movie set. Buckland helps bury that notion. The reader gets a revealing look at what it takes to make photos like these. Of course, as many of the fotogs mention, getting this kind of access to rock stars is impossible today, what with all the overprotective agents, publicists, and label reps. You get a sense of that in the book, with most of the really cool candid shots ending around the late ’70s.

R.E.M., Walter’s BBQ, Athens, Georgia (1984) by Laura Levine

Laura Levine was friends with the band and toured with them. Her photos of R.E.M. range from Stipe bathing in an old four-legged bathtub to the band in motel rooms across the country to Stipe and the B-52s having fun in a great swimming hole near her (Levine’s) home.

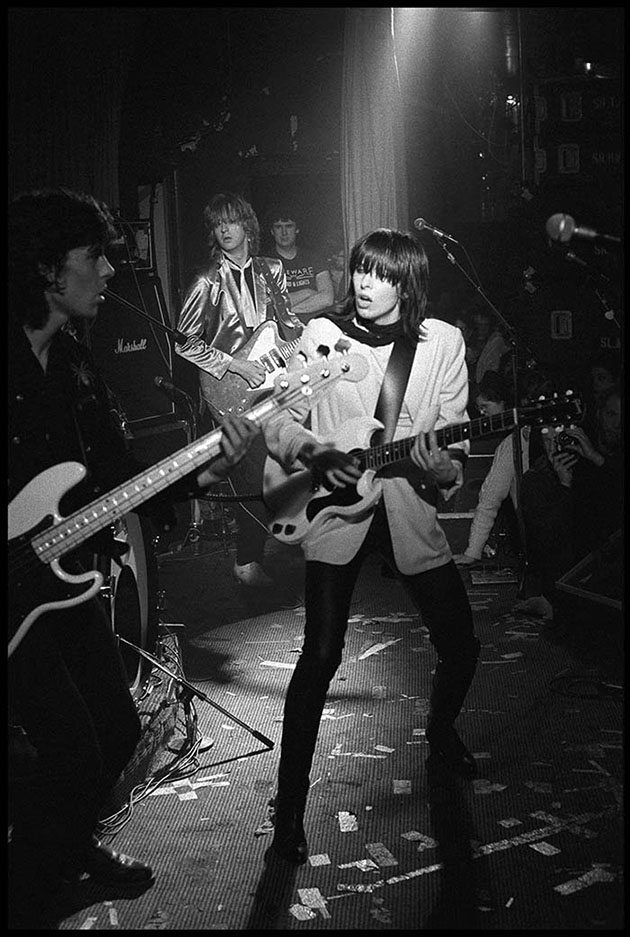

Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders, Nashville Rooms, London (March 9, 1979) by David Corio

In an interview with Jill Furmanovsky, Chrissie Hynde said, “Presentation is half it in rock and roll. It’s not just the music–there’s music and there’s attitude and there’s the image. It almost represents a way of looking at life.” (quote from The Moment, p. 166)

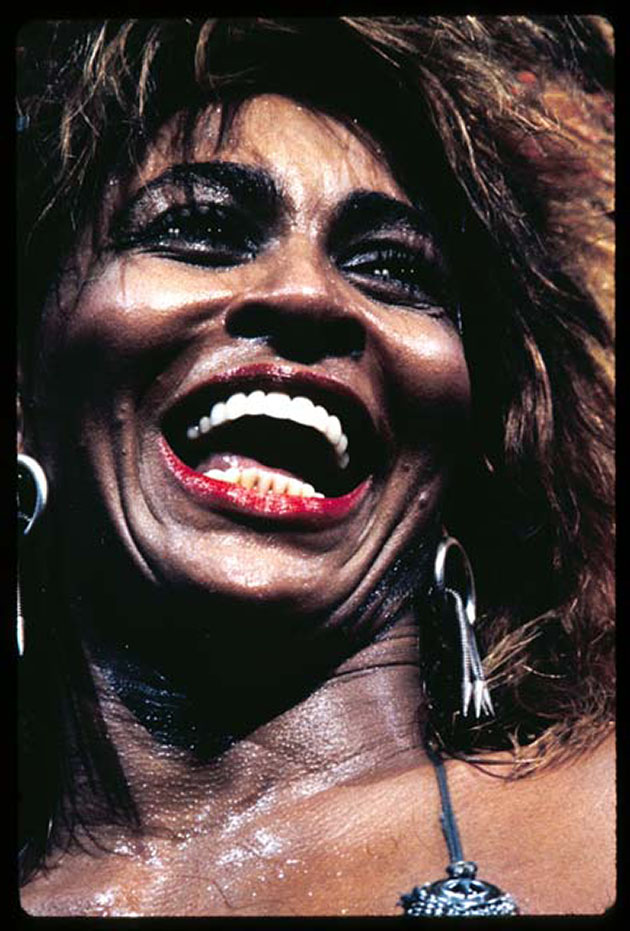

The book offers plenty of Beatles photos: the Fab Four as a five-piece back in Liverpool, stepping off the plane in San Francisco to play Candlestick, as solo artists in the ’70s and ’80s. Likewise, there’s no shortage of the Stones, Dylan, Madonna, and Elton John—all artists who not only know how to perform, but know the power of a strong image, and use it to their advantage.

Punk is well represented with photos by Bob Gruen (New York Dolls, Dead Boys), Stephanie Chernikowski (Blondie), Roberta Bayley (Ramones, Heartbreakers), Ian Dickson (Sex Pistols, Ramones), Jill Furmanovsky (Joy Division), Ed Colver (Minor Threat, Black Flag’s Damaged album cover shot), Ebet Roberts (Cramps), and more. Metal is not so well represented.

The Heartbreakers (1975) by Roberta Bayley

Bayley’s simple backgrounds highlight just how good she is in knowing exactly when to click the shutter to get the more deadpan moment out of each photo sessioon. Her photographs of punk groups are like police lineups, but totally compelling because the suspects are all so interesting. They are the perfect evocation of punk—the bodies slump, the smiles are nil, the clothes have holes, the eyes are shot and everyone is young.

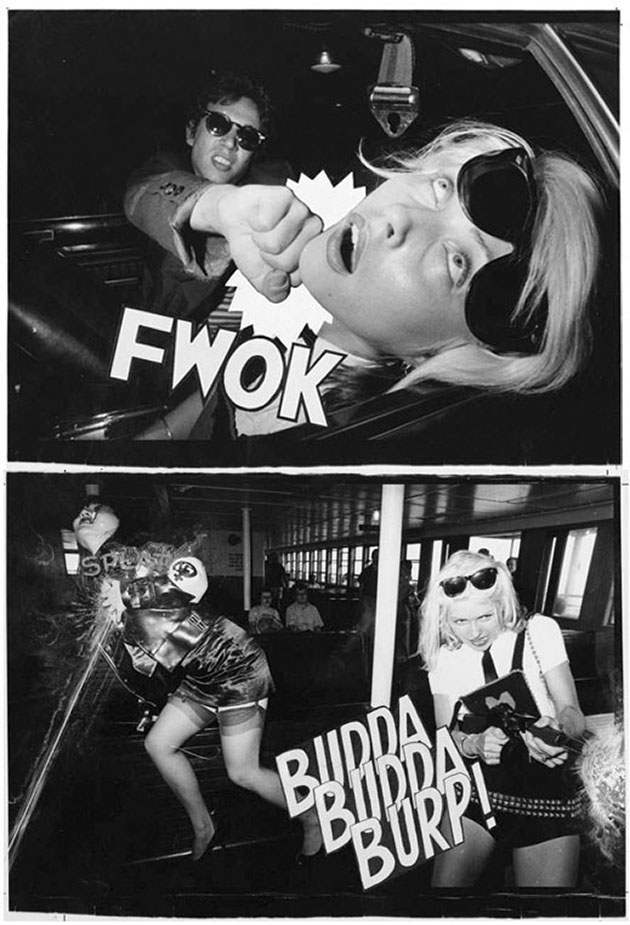

Richard Hell and Debbie Harry, Seventeenth Street, New York City / Anya Phillips and Debbie Harry, Staten Island ferry, New York. Photograph by Chris Stein, with graphics by John Holmstrom, “The Legend of Nick Detroit” PUNK #6 (October 1976)

Chris Stein, a founding member of Blondie, shot a number of photos for the irreverent 1970s New York magazine PUNK, including part of the “Legend of Nick Detroit” (PUNK #6). This fumetti was photo-directed by Roberta Bayley featured a who’s who of the mid-70s punk scene, including Debbie Harry and Anya Phillips as “Nazi Dykes” battling Nick Detroit (Richard Hell).

As cool as it is, especially for those who can’t get enough of behind-the-scenes action, the book isn’t without a few flaws. Despite an impressive and unexpectedly broad selection of images and photographers, the layout proves frustrating. Photographers who shot more than one iconic image have separate pages sprinkled about, each dedicated to the story of a specific image. It’s a good idea in theory, but the formatting is inconsistent—a few photographers have two or three images by different bands lumped together—and that makes it hard to follow a single photographer’s work throughout the book. Grouping by photographer would have made for a more cohesive experience.

A smaller but more frustrating layout quirk is how the text occasionally jumps to the back of the book—sometimes just a short paragraph. You’re getting into a story about Lew Allen shooting Buddy Holly on his tour bus and then have to fish around the back of the book for its conclusion. It’s an annoyance that starts out small and grows with each occurrence.

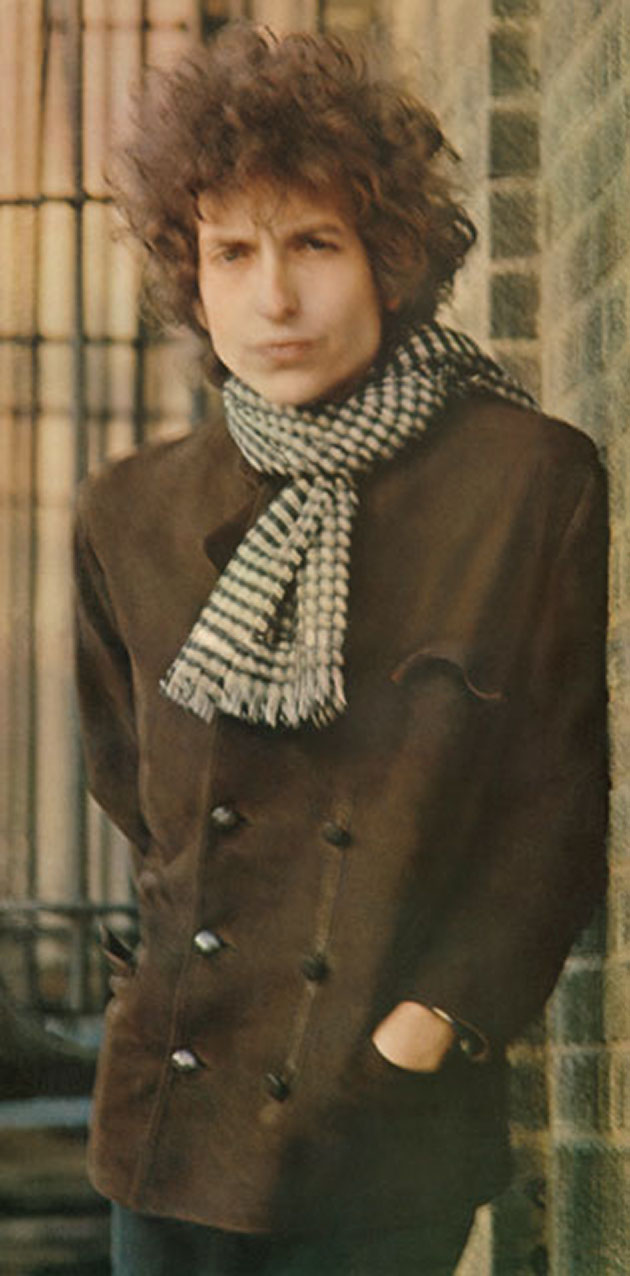

Bob Dylan, Blonde on Blonde, New York City (1966) by Jerry Schatzberg

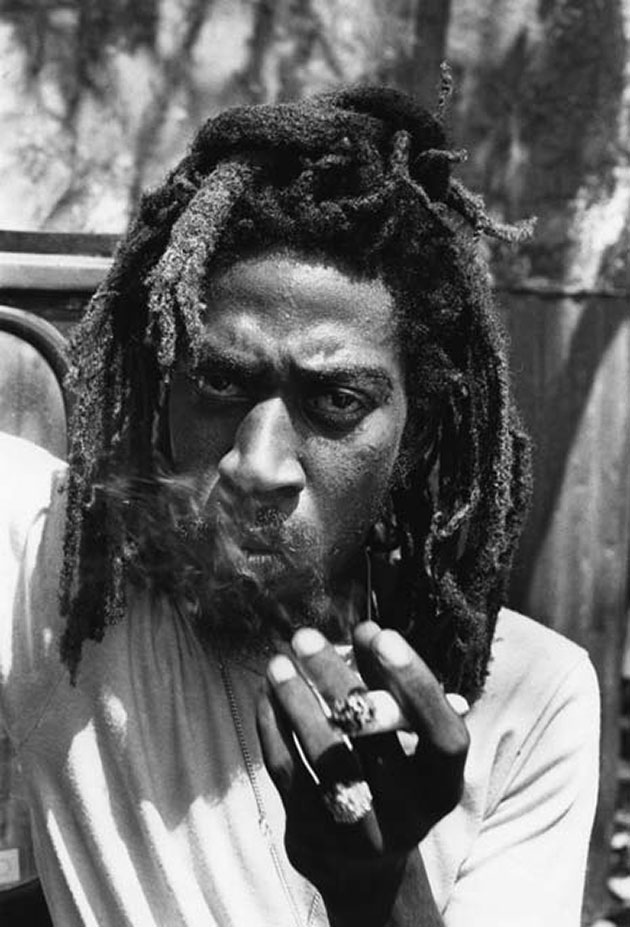

Bunny Wailer, Kingston, Jamaica (1976) by Kate Simon

“He was so intense, he could kill you with one glance,” Kate Simon says of Bunny Wailer. “I waited [in Jamaica] for a week for this session. I waited for him to come down from the hills and it was like the meeting at the O.K. Corral–I was ready and he was ready. It was a real meeting of the minds. How intense can you get? I enjoyed it. This man is serious business.”

“Musicians hate photo sessions, it is like going to the dentist. Especially if it is in a studio, the lights and all, and you have to stand there. We wouldn’t do that. We would say, ‘Let’s go up to Big Sur, lets go out to Joshua Tree, the desert, spend the night.’ That way you got the group away from all the girlfriends and the managers and you let things unfold and have a good time…We would have this adventure and photograph what happened and somewhere in there would be the image that was really these guys and it always worked out.” —Henry Diltz/p>

Formatting qualms aside, Who Shot Rock & Roll is an exhaustively researched, thoroughly captivating book, especially for people like me, whose love of music intersects with a love of photography. It takes the killer rock and roll photo book to the next level. The book also serves as a catalog for a traveling exhibit of the same name, opening October 30 at the Brooklyn Museum in New York.

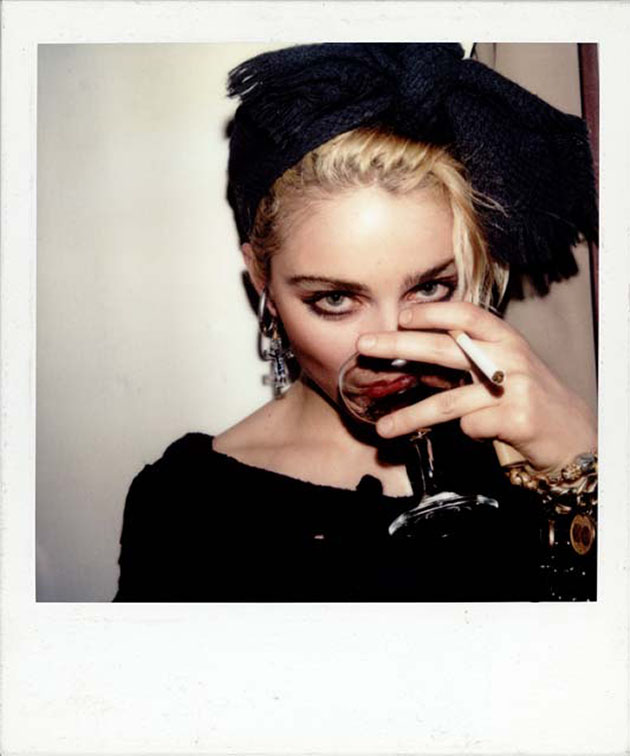

Maripol helped develop Madonna’s “look” during her “Boy Toy” and “Like a Virgin” phases—the crucifixes, jewelery, black rubber bracelets, skimpy skirts, and bodice-revealing blouses. They were friends, part of the same “downtown” scene in New York in the 1980s.