Image courtesy of WW Norton & Company

When I reach cartoonist David Shrigley at home in Glasgow, Scotland, he’s in the midst of cleaning up his computer desktop, which is cluttered with digital scans of his work. His routine involves filling notebook after notebook with sketches, so you can see how his desktop might feel overwhelmed. But he’s tidying up for his own sake. “The computer forgets things,” he quips. “Then it dies and takes your life with it.”

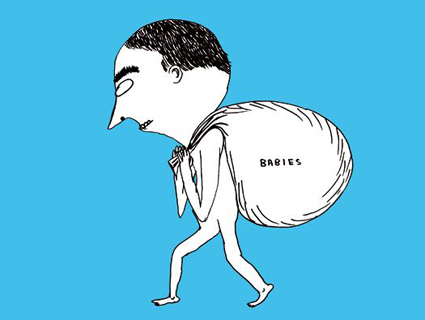

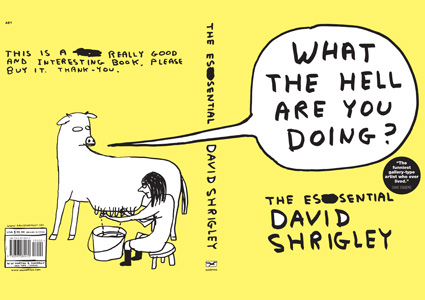

It’s an apt metaphor for an artist whose work is rife with perverse takes on death and dismemberment. But Shrigley, 44, isn’t morose: His approach to such topics, while not exactly lighthearted, is often hilarious, compelling Dave Eggers to call Shrigley “probably the funniest gallery-type artist who ever lived.”

As a kid, Shrigley was obsessed with the late ’70s British band Adam and The Ants. He started drawing in the hope of one day illustrating their record covers. While some critics might snark that his drawing skills haven’t improved since (his style is, um, pretty rough), Shrigley’s scope has expanded to include sculpture, photography, video (see below), and even opera—all of which take big acerbic swipes at the mundane conventions of everyday life.

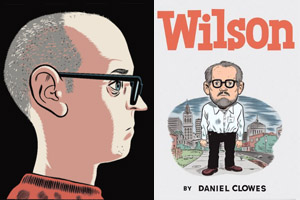

What The Hell Are You Doing: The Essential David Shrigley, out this week, is a thick compendium of Shrigley’s best cartoons, photography, and sculpture. You can check out our slideshow of selections from the book. (Warning: Bring a dark sense of humor.) Meanwhile, I grilled Shrigley on his unique style, his fixation with death, and his upcoming opera featuring, among other things, a banana, an egg, and a potato.

Mother Jones: Your work is sometimes called “childlike” and “deliberately limited.” Does that offend you?

David Shrigley: Well, I guess everybody can be offended by certain things. I think the work is what it is, you know? I don’t really get offended when people say something about the work that you don’t necessarily agree with. I guess the term that I think is slightly wrong, or where people misunderstand what the work is, is “faux naive.” I don’t think the work is faux naive. I think it’s just naive. It’s like, I’m not pretending to do anything in a really crude fashion, I just am doing it in a really crude fashion.

MJ: Umm, right.

DS: I’m not pretending to be somebody who’s got really limited craft skills. I just am a person who’s got really limited craft skills. Another term I take issue with is “outsider-ish.” I’m definitely not an outsider artist. I’m very much an insider artist, you know, because I show at fancy galleries in Chelsea in New York City, and I get written about in art magazines, and I’m not, like, in a mental institution. I’m a regular guy who went to art school.

MJ: How did you come to adopt your “really crude fashion”?

DS: I studied fine art at Glasgow School of Art many years ago. For four years, I made paintings and photographs and sculpture and basically stuff that would have required me to have a studio to continue that kind of practice when I left. I’d always made drawings in the way I do now, but I’d never really thought that they could be artwork. And I think when I left art school I thought, “Well, maybe I could just make this kind of art, these kinds of drawings, and that would be my artistic output, because I can’t afford to have a studio.”

MJ: So it was a practical decision?

DS: Yeah, it was just kind of an abbreviation of my artwork. I just decided to work in this medium, and I think I can say pretty much everything I want to say in a small black and white drawing. So it was kind of a practical decision, but it’s become what I’m known for, I guess, and that’s what’s made me a living for a long time. I feel like I could do something else. I mean, I do make work in a couple of different media.

MJ: Yeah, this book also has photography, and photographs of sculptures. Do you want to do more of that kind of thing?

DS: I sort of got caught up in the crossover between digital and film-based photography. Once that change-over happened, which was in the early ’90s, I suddenly didn’t want to make work in the photographic format anymore. I think it was to do with the paper element of photography. I felt like this black-and-white, chemical-based photography I kind of understood. But once it became a digital thing, I just didn’t really know what to do with them after I’d taken them, somehow. So I stopped doing that, and I also started making animated films around that time, so maybe it was a case of one-in-one-out as far as my media were concerned.

MJ: Right. It sounds like the course of your artwork has been guided by whichever media works for you at the time?

Courtesy WW Norton & CompanyDS: I think circumstance plays a big part in terms of what I do. For example, if I wasn’t ever able to show in an art gallery I probably wouldn’t really make very much sculpture. But I’ve had the opportunity to show in big spaces, so I want to fill up that space in the same way you might want to fill up a page. I’m never really that worried about doing something a little different, ’cause it always just seems to fit into what I want to do. Like I’m making an opera at the moment with a classical composer, and it’s a really strange project.

Courtesy WW Norton & CompanyDS: I think circumstance plays a big part in terms of what I do. For example, if I wasn’t ever able to show in an art gallery I probably wouldn’t really make very much sculpture. But I’ve had the opportunity to show in big spaces, so I want to fill up that space in the same way you might want to fill up a page. I’m never really that worried about doing something a little different, ’cause it always just seems to fit into what I want to do. Like I’m making an opera at the moment with a classical composer, and it’s a really strange project.

MJ: Are you writing the words for it, or doing the scenery, or what?

DS: Well, I’m writing the words, and I’m sort of the production designer in a way, so I’m designing all the costumes. But I’m not making them myself.

MJ: What’s the opera about?

DS: It’s about cookery. It’s classically scored, and all the words are sort of sung, but not really—they’re just scored, so the words are spoken or shouted or whatever in a certain place along with a chamber orchestra. It’s quite angular, not easy listening, quite modern classical music, which is really strange. It’s sort of like a faux TV cookery show, and these two main characters who are sort of the presenters of the show, they make this meal for a dinner guest that arrives at the end, who’s sort of this sinister-type scary character. The other characters are food, ingredients for the meals. So it’s pretty strange, but kind of funny.

MJ: The characters are ingredients?

DS: Well, yeah. There’s maybe 10 characters, and three are human beings and the rest of them are, like, one’s a banana, and a potato, and an egg, and other things.

MJ: Oh, I thought maybe you meant the human characters are being cooked.

DS: Well, there’s some questionable behavior at the end; some unsanitary things that happen—and illegal things. But yeah, you kind of need to see it to understand it. The composer is a guy whose work I really like, and I figure even if what I’ve written is a lot of rubbish it’ll still be really good, ’cause his music is really good.

MJ: You have a very edgy sense of humor. Where does that come from?

DS: I don’t know. It’s like asking somebody, “Where did you get your personality from?” Obviously I have quite a singular sense of humor that marks me out as a little bit, but I don’t know. I think it’s constantly changing. One of the things that I often think about is: If I spend all my time making art, then I’m never really having any experiences to make the work about. Am I just making it about things that I find on the internet or hear on the radio? I guess I just always want to surprise myself and say something that I’m not really quite sure where it came from, and it sort of makes sense and has a kind of profundity to it. Sometimes it happens, sometimes it doesn’t. I guess I’m trying to make something, but I’m not really quite sure what it is. I kind of know how to do it, but I’m not exactly sure what I’m doing.

MJ: Since some of your work is, well, kind of ridiculous, how do you feel about having it hanging in earnest galleries like the NYC MoMA or the Tate in London?

DS: Um, well, I guess it wasn’t something I ever aspired to, but I’m pretty proud of it. It’s not like I’m trying to take the piss out of anybody. I am a serious artist in my own right, in the sense that I’ve spent my entire life being an artist and trying to be an artist and making work. They’ve got to have some artwork in there, so it might as well be mine, as well as all the other crap that’s around. I don’t want to just spend my life ridiculing something that I find ridiculous, although there is an element of satire in my work. I like comedy but I guess I don’t think [my art] is that funny, either. It’s too dark and a bit weird in places to be genuinely, uniformly hilarious and function as comedy.

MJ: I can tell you take the process seriously, even when your subject matter is absurd.

DS: Yeah, in terms of editing it and wanting it to be a certain way, it can be a bit of a ball-busting exercise. You know, my life’s not one hilarious big joke. I have to be quite dedicated and I have to work at the weekends and, you know, I get bad posture from sitting at the drawing board all day.

MJ: Occupational hazards.

DS: Exactly.

MJ: Why so many of your drawings depict death or dismemberment?

DS: I suppose the big themes are the ones that interest me, and that ones that have the potential to be the most comic. I don’t really want to tell jokes about trivia; I’d kind of rather joke about things like life and death.

MJ: Is that a way of taking an abstract concept and making it more digestible?

DS: Yeah, but there’s not really a strategy. I never sat down and decided to make work about life and death. It just all comes out of my head like water pouring out of a jug. The work, I suppose, is made in the editing, whereby I make literally hundreds of drawings, and then a much smaller percentage of those become the finished work. I guess I must just be obsessed with death. Apparently you think about it a lot more as you get older. Maybe you could chart how when I was in my 20s I talked about sex all the time, and now I’m in my 40s and it’s just death.

To see some of Shrigley’s moribund illustrations, check out our slideshow here.