Enrique Metinides

William S. Burroughs once described Mexico City as “sinister and gloomy and chaotic, with the special chaos of a dream.” In fact, the sprawling megalopolis, home to 20 million people, is insistently literal—at once intensely alive and decaying, filled with bodies and odors and clangor.

For the last 50 years, photographer Enrique Metinides has cataloged Mexico City’s human calamities: murders, suicides, plane crashes, car wrecks, derailed trains, collapsed buildings, gas fires. His photographs—most of them published by the tabloids La Prensa and Alarma!—are Mexico’s answer to Weegee’s New York City crime scenes. Like Weegee, Metinides has an eye for cinematic detail and a kind of point-blank lyricism. His photos have a beginning, a middle, and an end; to look at one is to experience anew a tragedy that is eternally in media res.

Metinides began taking pictures at age 10 with a box Brownie camera his father gave him. By age 12 he was a prolific street photographer, documenting the city’s traffic accidents. He was such a fixture at these smash-ups that local police dubbed him El Niño (“the boy”), a nickname that has stuck over the years.

He launched his professional career with Mexico City tabloids in 1947. Taking cues from a shortwave radio, Metinides raced hell-for-leather to the latest scene of murder or suicide, one of many such press photographers vying for the most sensational shot. The images were meant to sell newspapers, but in Metinides’ case they also offered a statement about death in a modern city. In many of his most compelling photos, it’s the gaggle of spectators—variously shell-shocked or stoic or bemused—that stokes our curiosity. The crush of onlookers is a casebook of human types, and the beginning of an interaction—witnessing, looking, seeing—that erupts beyond the frame to implicate its viewers.

Like Boris Mikhailov, Luc Delahaye, Jacob Holdt, Diane Arbus, and other purveyors of “shocking” imagery, Metinides exploits the primal thrill of encountering a stranger’s catastrophe. This ethical conundrum is synonymous with his artistic agenda and is a statement about our common bond as witnesses. Why are we drawn to incidents of calamity and violence? Why is the “fascination of the abomination,” to quote Conrad, always so persuasive?

In the words of curator and filmmaker Trisha Ziff: “In describing the events and their participants, [Metinides’] commentaries are straightforward and without any hint of cynicism. He remembers in detail the names, characters, and narratives behind the photographs. It is this obsession with remembering that gives his images their humanity, and ensures that the sufferings of those who appear in them do not merely end up as statistics or yesterday’s news.”

The photographs and accompanying captions are excerpted from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, a retrospective newly published by Aperture.

The Regis hotel in downtown after the 1985 earthquake. Not only did the hotel collapse, but so did nearby stores, restaurants, and cabaret halls. The Torre Latinoamericano is in the background.

©

A young woman cries as she sits next to her boyfriend, who had been killed in a robbery that went badly wrong. He looks like he is asleep.

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)

Mexico City, April 29, 1979.

Adela Legarreta Rivas was a Mexican journalist. She had a press conference that day where she presented her latest book. She had been to the beauty parlor that morning where she had her hair and nails done. On the way home from the beauty parlor, she was hit and killed by a white Datsun on Avenida Chapultepec.

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)

North American kids surfing in a sudden flash flood on the corner of Horacio and Presidente Masaryk.

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)

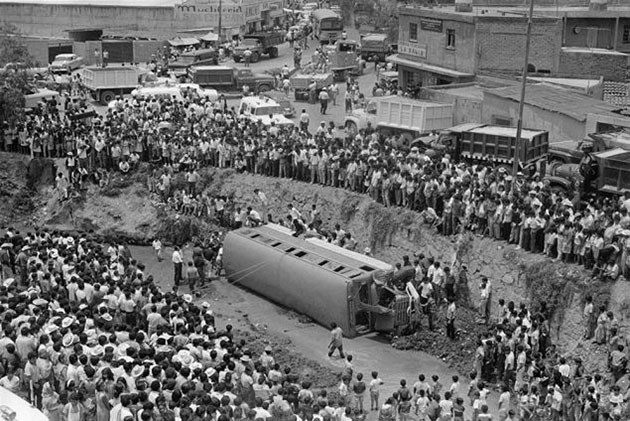

Extract from La Prensa, May 25, 1969.

“Hundreds of people gather to look at an overturned bus, which fell into the San Esteban river after its brakes failed on the route between Mexico City and Huixquilucan. Inside were 23 screaming children. When they turned the bus over, they discovered a dead child who had fallen through an open window.”

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)

Highway to Querétaro, September 1967.

Red Cross workers take a young woman, who was on her way to a party, from the scene of a crash.

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)

Colonia Doctores, Niños Héroes, Mexico City, 1966.

This woman did not have money to buy a coffin for her child, who had been killed when a bus ran over him. She went to a coffin shop near the hospital and started praying and begging. After some time, she was surrounded by people who asked what happened. Together, they each gave a little bit of money to help her. With that and a discount from the coffinmaker, she was able to bury her child. She walked nine kilometers with the coffin to her home.

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)

Someone dumped the body of a murdered man in the canal at Xochimilco. The lifeguard, attached to a cord for his own safety, swam out to the body. On the opposite bank you can see onlookers reflected in the water.

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)

Mexico City, 1977.

Bertha Ibarra Garcia, while walking through Chapultepec Park, asked a policeman to show her the oldest tree. Later that day, the same policeman found her hanging there. A note in her bag said that today was her daughter’s quinceañera (15th birthday). Her daughter had been taken from her when she was just nine years old. Bertha had wanted to go to her daughter’s party, but the girl’s father would not let her. Also in Bertha’s bag was a photo of her daughter at nine years old.

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)

With this story, La Prensa ran: “‘I wanted to know what death was like,’ said Antonio N., 45 years old, after two rescue workers persuaded him not to jump. The man had no work and a lot of worries.”

©Enrique Metinides, Courtesy 21BERLIN, from 101 Tragedies of Enrique Metinides, (Aperture, 2012)