Pipers, fictional (left) and real.Harel Rintzler/PatrickMcMullan.com/Sipa USA/AP

AT 24, PIPER KERMAN boarded a flight to Belgium wearing slacks and a nice jacket, carrying a suitcase full of cartel cash to be delivered to a West African kingpin by her heroin-dealing girlfriend. Kerman didn’t run with that crowd for long, but her crimes caught up with her; she ultimately pleaded guilty to a felony money-laundering charge.

Her 13-month stint in federal prison became the basis for her 2010 bestseller, Orange Is the New Black, which was adapted into an acclaimed Netflix series by Weeds creator Jenji Kohan. The show—whose second season is in the works—follows Piper Chapman (Taylor Schilling) as the Whole Foods-shopping Smith College alum bumbles her way through life on the inside. Orange has been hailed for its realism and its diverse and well-developed cast of female characters, but the show also has caught flak for its reliance on a privileged white protagonist. At the height of the hoopla, I caught up with Kerman, now 44, to talk about sadistic guards, crocheted phalluses, and her top three prison reforms.

Mother Jones: At what point did you decide to write about all of this?

Piper Kerman: The woman I shared a cube with for many months turned to me one day and said, “You go home and write a book about this, bunkie.” I was not necessarily planning on writing a book, but when I came home, almost every single person I knew wanted to hear about my experience. I had a sense that it would interest people who would not otherwise pick up a book about prison. I wasn’t writing for the choir.

MJ: Tell me a little bit about your upbringing.

PK: I come from a very ordinary, middle-class family. Both of my parents are teachers, they’re both retired now. I was incredibly fortunate to go to a great college like Smith, but I needed a lot of financial aid. Many of the privileges that are true for me and for my character are things that a lot of middle-class folks take for granted, but obviously are not available to a huge percentage of the American population. Where that plays out really sharply is access to counsel. If I had not been able to afford really good private lawyers, I would probably have served a lot more time.

MJ: How do you respond to the criticism that you had it easy in prison?

PK: If it bothered me, I wouldn’t have written a book. Access to counsel, the color of my skin, a good education, all of these things contribute to treatment that a person who does not have those privileges would not enjoy. I think it’s fantastic for those things to be discussed.

MJ: If you could dictate the three most crucial prison reforms, what would they be?

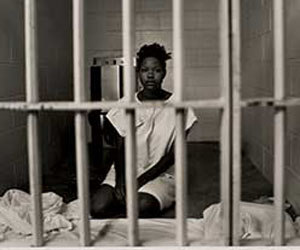

PK: I would reform sentencing guidelines. Eric Holder’s recent announcement will make some improvements, but really Congress and state legislatures have to reform sentencing at the front end. Also public defense reform: Eighty percent of criminal defendants are too poor to afford a lawyer. Eighty percent! If everybody accused of a crime received zealous defense—I don’t like the word adequate—we’d have a more fair and also a less costly system. And juvenile justice reform, because if we can make changes for young folks on the wrong path, that will have dividends for all of us. Juvenile justice systems are sometimes really, sickeningly horrifying.

MJ: I was blown away that you had to wait six years to start your sentence.

PK: I spent six years in pretrial, a year incarcerated, and two years of probation. It really seems like a dumb use of public resources because there was frankly not a threat of me committing new crimes during that entire time period.

MJ: What was it like having this hanging over you for so long?

PK: It was really hard. I was really scared and really didn’t want to go, of course, but after waiting six years you’re like, “Let me, no matter what, get this over.” I walked into prison 11 years after committing my crime. I was certainly much more emotionally mature and a much more thoughtful person than I had been. And I’m sure that I had the ability to draw on more within myself to contend with the experience.

MJ: What did you draw on?

PK: My family and my friends, their ability to visit. Receiving letters. Being able to make phone calls. All of these lifelines are incredibly important, not only in terms of the day-to-day emotional health, but in terms of whether folks keep their ties to the communities to which they’re gonna return. Some jails are getting rid of mail call. It just boggles the mind—to cut people off so completely from the world! It really stacks the deck against people. I also was able to draw on the strength of the other women I was locked up with. There’s a prison trope, “You walk in here alone and you walk outta here alone,” but the truth is that it is the relationships that allow us to survive the experience and change and come home successfully.

MJ: What aspects of prison life defied your expectations?

PK: For me, the big fear was violence. If you watch practically any television show about prisons, prisoners are often depicted as uncontrollably violent. I found a very different situation. Granted, I was in a minimum-security women’s prison.

MJ: And those perpetrating violence or discomfort are often the guards.

PK: I was much more scared of guards than the other women.

MJ: Was there a guard “type?”

PK: The system is dehumanizing to everyone within it. There was a small number of guards—three or four guys—whom you might describe as sadists, and then a huge number of people just trying to get through the day. There also were a small handful of staff who were thoughtful and pretty interested in the prisoners, and who would sometime expend simple and small acts of kindness, or just the way they talk to you. Everybody’s human. I’ll leave it at that.

MJ: What are the worst things you witnessed?

PK: Just capricious or irrational cruelties from the system, like a woman being denied permission at the very last minute to attend her brother’s funeral because her family came to pick her up in a car that was different than what was in her paperwork. And this was a woman who was due for release in like two weeks! That was just so cruel and stupid. The separation of women and their children, particularly small children, is so senseless. The vast majority of the women I did my time with were there for low-level drug offenses, or nonviolent financial crimes. Seeing the impact of those sentences on those children will break your heart.

MJ: What gave you hope?

PK: To see how, in their own unique and sometimes sly or clever ways, women were defiant and did all kinds of things to hold on to their humanity. Like celebrating a holiday or cooking in the microwave—or crocheting incredibly realistic penises! But it’s a lot easier to be resilient in a minimum-security setting.

MJ: Would you say this experience has changed you a lot?

PK: Yeah. I come from a family that I would describe as progressive. My parents are very different tha their depiction on the show. They’re both very committed to social justice. But the ideas of progressivism and equity and fairness for everybody take on an entirely different cast when you stand shoulder to shoulder with women you are friends with and you see how differently they are treated. That’s not something you can just forget.

MJ: Have you kept in touch with them?

PK: I do keep in touch with a number of the women depicted in the book. And in the process of the book and the show coming out, more and more people have gotten in touch, which is really great.

MJ: Are they still there at Danbury?

PK: Almost everyone has come home. Some are doing great things and living happy lives. Some have returned to prison, which is really tragic and makes me really sad. And there are women who have come home but are struggling because of all those collateral consequences that accompany going to prison.

MJ: When you got out, a friend created a job for you. How have your subsequent employers reacted to your conviction?

PK: I had an existing professional network and many years of professional experience, so I haven’t had to fill out a job application where you have to check the box and say, “Yes, I have a felony conviction.” Everybody who comes home needs to be able to tap into networks that will help them. Work, and access to work—the dignity of work—and folks being able to support themselves and their families is the number one thing I hear from other people with felony convictions—the number one problem.

MJ: So how did Jenji Kohan pitch the show to you?

PK: She didn’t really pitch me. She asked tons and tons of questions, and that actually was really reassuring—that she didn’t have a totally canned, preconceived idea about what it was she wanted to do. She had obviously read the book. And obviously she has an incredible track record.

MJ: What do you think of the show—and do you get any veto power?

PK: I think the series is fantastic. I am a consultant, which does not mean veto power. Basically, if Jenji or one of the writing team or the production team has questions, I answer them. I read the scripts and I give them feedback, and I try to keep it very narrowly focused on helping them create a world that reflects what life is like in a minimum-security women’s federal prison.

MJ: Any favorite characters or specific things you like about the show?

PK: The show has the opportunity to put many different women’s stories into the spotlight. That was sort of the most exciting thing. On the micro scale, I am so thrilled and so proud of Sophia Burset, the transgender character. I had a neighbor in my prison dorm who was transgender, and I eventually moved into her bunk when she went home. That character is fantastic, and Laverne Cox, who plays her, is fantastic. Also, I did not ever spend time in solitary, but they chose to make it an important part of the first season, and I was really happy to see that. There are a number of characters struggling with substance abuse or mental illness. Jenji and her writers deserve a ton of credit—the show has to entertain but it is tackling really important themes.

MJ: Are you involved in season two?

PK: I am still a consultant. We’re already shooting, here in New York where I live. It’s going to be good.

MJ: Sneak preview?

PK: I could tell you, but then they’d kill me!

MJ: Given that your imprisonment ultimately led to so much success for you, would you take it back now?

PK: In a heartbeat. Forget about me. Many women I was locked up with suffered from the ravages of drug addiction; those relationships made crystal clear to me the consequences of my actions. And the consequences for my family! Seven years of worry and sleepless nights for my parents. I would do anything to go back and erase that.