<a href="http://www.thinkstockphotos.com/search/#/f=PICHVX/A|OSTILL">OSTILL</a>/Thinkstock

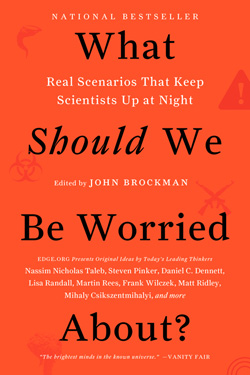

I’m kind of a worrier, so naturally I picked up this book called What Should We Be Worried About? Editor John Brockman, the curator of Edge.org, asked a bunch of really smart people—scientists, writers, journalists, tech gurus, folks like that—to write essays about what keeps them up at night. It’s that simple.

My wife commented that perhaps this wasn’t the sort of book I should be reading, but as a curmudgeon, I had to disagree. It’s actually sort of validating to read about all these other people’s worries. Plus, the writers keep ’em short—too short, in the case of Terry Gilliam—and the breadth of the worriers clues you in to a wide range of worries you never even knew you needed to worry about. How awesome is that?

They’re not all great, of course. A handful of the chapters are ponderous or predictable, but with 150 to choose from, you can pick out your faves. British neuroscientist Kate Jeffery worries interestingly about our rarely challenged scientific efforts to overcome natural death: “We are not Antarctic sponges or blue-green algae—we die for a reason.” Boing Boing editor Xeni Jardin, who has written much about her own struggles with breast cancer, worries that the war on cancer has failed miserably: “We’re still using the same brutal chemo drugs, the same barbaric surgeries, the same radiation blasts as our mother and grandmothers endured decades ago.”

Kevin Kelly, of Wired fame, warns us about the coming “unpopulation bomb.” Anthro-archeologist Timothy Taylor frets about Armageddon “not as a prelude to an imaginary divine Day of Judgment, but as a particular, maladaptive mindset that seems to be flourishing despite unparalleled access to scientific knowledge.” Indeed, more than a few writers worry we may be headed toward a new Anti-Enlightenment age, in which ideology trumps science. (I wonder where they get that idea?) And in an essay that, as a parent, I found particularly thoughtful, MIT’s Sherry Turkle explores why we need solitude, and how our shiny gadgets undermine our capacity to be comfortable with it.

I also really liked the following excerpt by the author Nicholas Carr, describing a phenomenon many of us have experienced personally. It’s one of a growing number of concerns that makes one wonder whether the cult of Steve Jobs had it wrong all along, and whether most of us will bother to look up from our phones for long enough to notice.

****

The Patience Deficit

By Nicholas G. Carr

I’m concerned about time—the way we’re warping it and it’s warping us. Human beings, like other animals, seem to have remarkably accurate internal clocks. Take away our wristwatches and our cell phones and we can still make pretty good estimates about time intervals. But that faculty can also be easily distorted. Our perception of time is subjective; it changes with our circumstances and our experiences. When things are happening quickly all around us, delays that would otherwise seem brief begin to seem interminable. Seconds stretch out. Minutes go on forever. “Our sense of time,” observed William James in his 1890 masterwork The Principles of Psychology, “seems subject to the law of contrast.”

In a 2009 article in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, the French psychologists Sylvie Droit-Volet and Sandrine Gil described what they call the paradox of time: “Although humans are able to accurately estimate time as if they possess a specific mechanism that allows them to measure time,” they wrote, “their representations of time are easily distorted by the context.” They describe how our sense of time changes with our emotional state. When we’re agitated or anxious, for example, time seems to crawl; we lose patience. Our social milieu, too, influences the way we experience time. Studies suggest, write Droit-Volet and Gil, “that individuals match their time with that of others.” The “activity rhythm” of those around us alters our own perception of the passing of time.

Given what we know about the variability of our time sense, it seems clear that information and communication technologies would have a particularly strong effect on personal time perception. After all, they often determine the pace of the events we experience, the speed with which we’re presented with new information and stimuli, and even the rhythm of our social interactions.

That’s long been true, but the influence must be particularly strong now that we carry powerful and extraordinarily fast computers around with us. Our gadgets train us to expect near instantaneous responses to our actions, and we quickly get frustrated and annoyed at even brief delays. I know that my own perception of time has been changed by technology. If I go from using a fast computer or Web connection to using even a slightly slower one, processes that take just a second or two longer—waking the machine from sleep, launching an application, opening a Web page—seem almost intolerably slow. Never before have I been so aware of, and annoyed by, the passage of mere seconds.

Research on Web users shows that this is a general phenomenon. Back in 2006, a famous study of online retailing found that a large percentage of online shoppers would abandon a retailing site if its pages took four seconds or longer to load. In the years since then, the so-called Four Second Rule has been repealed and replaced by the Quarter of a Second Rule. Studies by companies like Google and Microsoft now find it takes a delay of just 250 milliseconds in page-loading for people to start abandoning a site. “Two hundred fifty milliseconds, either slower or faster, is close to the magic number now for competitive advantage on the Web,” a top Microsoft engineer said in 2012. To put that into perspective, it takes about the same amount of time for you to blink an eye.

A recent study of online video viewing provides more evidence of how advances in media and networking technology reduce our patience. Shunmuga Krishnan and Ramesh Sitaraman studied a huge database that documented 23 million video views by nearly seven million people. They found that people start abandoning a video in droves after a two second delay. That won’t surprise anyone who has had to wait for a video to begin after clicking the Start button. More interesting is the study’s finding of a causal link between higher connection speeds and higher abandonment rates. Every time a network gets quicker, we become antsier. As we experience faster flows of information online, we become, in other words, less patient people.

But it’s not just a network effect. The phenomenon is amplified by the constant buzz of Facebook, Twitter, texting, and social networking in general. Society’s “activity rhythm” has never been so harried. Impatience is a contagion spread from gadget to gadget.

All of this has obvious importance to anyone involved in online media or in running data centers. But it also has implications for how all of us think, socialize, and in general live. If we assume that networks will continue to get faster—a pretty safe bet—then we can also conclude that we’ll become more and more impatient, more and more intolerant of even microseconds of delay between action and response. As a result, we’ll be less likely to experience anything that requires us to wait, that doesn’t provide us with instant gratification. That has cultural as well as personal consequences. The greatest of human works—in art, science, politics—tend to take time and patience both to create and to appreciate. The deepest experiences can’t be measured in fractions of seconds.

It’s not clear whether a technology-induced loss of patience persists even when we’re not using the technology. But I would hypothesize (based on what I see in myself and others) that our sense of time is indeed changing in a lasting way. Digital technologies are training us to be more conscious of and more antagonistic toward delays of all sorts—and perhaps more intolerant of moments of time that pass without the arrival of new stimuli. Because our experience of time is so important to our experience of life, it strikes me that these kinds of technology-induced changes in our perceptions can have broad consequences.

In any event, it seems like something worth worrying about, if you can spare the time.

Reprinted by permission of Harper Perennial. Copyright © 2014 by Edge Foundation Inc.