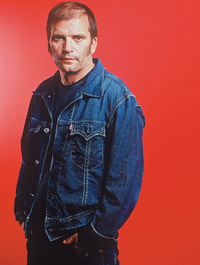

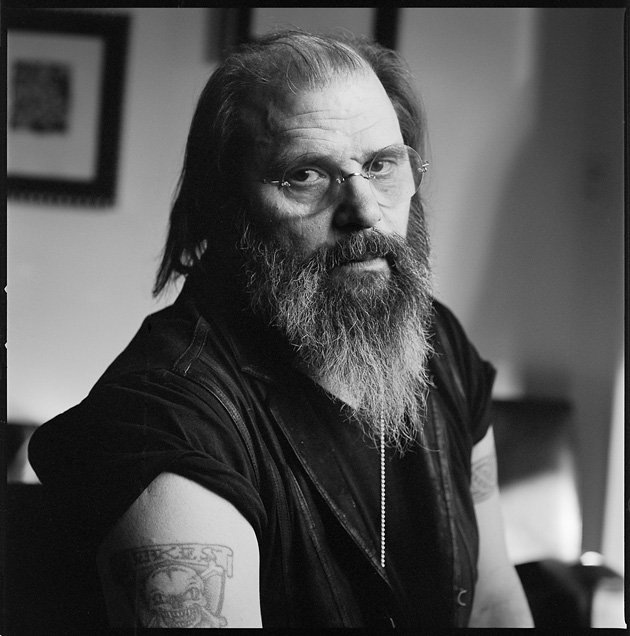

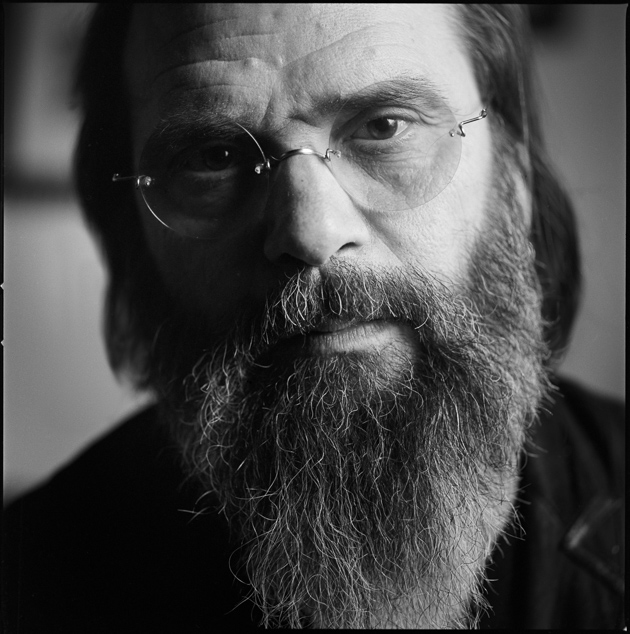

At the age of 60, songwriter Steve Earle has 1,000 stories, six ex-wives, and 16 studio albums recorded over nearly three decades. His latest, Terraplane, is a collection of blues-based songs he wrote during a difficult separation from his latest wife, songwriter Allison Moorer—with whom he has a five-year-old son. (His musician son, Justin Townes Earle, is from a previous marriage.)

Earle is one of the Great American Songwriters, an artist whose deft song structures juggle incisive character studies, personal confession, and passionate politics. His career was born of late-’70s Nashville, where his mentors Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark—along with the likes of Kris Kristofferson, Mickey Newbury, Waylon Jennings, and Willie Nelson—were pushing the creative, personal edge of songwriting, even as the Nashville establishment moved toward pop country.

After several years as a songwriter-for-hire, Earle found commercial success with his 1986 debut, Guitar Town, which soared to No. 1 on the Billboard Country charts. Successive albums Exit Zero and Copperhead Road also did well. But Earle lived turbulently and struggled with addiction. He was arrested twice in the 1990s for drug possession (heroin and cocaine) and sentenced to a year in jail, serving 60 days before being released and going into rehab. Now he’s clean and sober. Indeed, you may have spotted him on HBO’s The Wire—Earle has done a good bit of film and TV acting as well—as a 12-step mentor to the character Bubbles, who was trying to kick heroin. Earle also had a recurring role on Treme, the HBO drama set in post-Katrina New Orleans.

Since his recovery, Earle has maintained a steady output of albums supported by a passionate fan base. With his next one already formed in his mind, Earle is as restless as ever. I photographed him at home in Greenwich Village, where he’s lived for the past 10 years, but he just kicked off a 32-city American tour, so catch him if you can.

Mother Jones: Whenever I hear you speak about music, history, or anything, really, I’m always amazed by your encyclopedic recall.

Steve Earle: It’s just my job. I’m basically a folk singer, and that job is musicology to a certain extent. There is an academic quality to it—which is one of the things that people criticize.

MJ: At a recent show, you mentioned some of your historical influences for Terraplane. Would you call it a Texas blues-based album?

SE: No. Just a blues record. But I’m from Texas. There’s not a Los Angeles shuffle. There’s not a New York shuffle. There’s only a Chicago shuffle and a Texas shuffle. Chris Masterson, my guitarist, was born in Louisiana but he grew up in Houston, and his dad fixed everybody’s amps. He was out playing in pretty serious blues bands, sitting in at Antone’s in Austin when he was 14, 15. He was one of those guys.

MJ: Was there any element of your Texas upbringing you were trying to bring to the new album?

SE: Sure. I mean, I’m not saying it’s not a Texas blues record. I’m just saying that I didn’t set out to make a Texas record. I was in a blues band when I was 13. We moved to the South Side of San Antonio from the North Side, and everybody was a cowboy and greased their hair back, and I couldn’t find anybody like me, except for these three or four kids who were listening to Canned Heat and the Butterfield Blues Band. We started a band, and that’s one of the only bands I was in growing up. I was just a singer. I got kicked out for wanting to do a Donovan song—plus a guy that had a PA system came along and I didn’t have one. As for influences, Canned Heat had a lot to do with this record. And then ZZ Top comes along. ZZ Top played proms and shit where I grew up. So did the Moving Sidewalks, Billy Gibbon’s band before ZZ Top, and so did the 13th Floor Elevators.

MJ: Terraplane has these two songs right next to each other, “Ain’t Nobody’s Daddy Now” and “Better Off Alone.” It just struck me how they’re at totally opposite ends of the emotional spectrum of a breakup song. One is rambling and giddy. The other is wrenching, angry, and sad.

SE: They’re the same experience. They’re just, you know, different voices. They’re all me. I’m going through it right now with Allison. She’s heard some of the record and gotten pissed off about it. I don’t have any other experience to write about this year. I wish I did. But still, it makes me feel better. I don’t think there’s a mean moment on the record. I think, some stuff is just me basically puffing out my chest and trying to make myself feel better, a little less fucked over.

My therapist thinks that I really want to be alone so I choose relationships that are bound to fail. I’m not sure I buy that. I think I don’t want to be alone, just like anybody else doesn’t, but I’m okay alone. More and more as I get older I’m okay. Although I’m not really alone. The little boy is here often. If she takes him someplace else, I don’t know what I’ll do. Odds are that won’t happen. We’ll see.

MJ: Your albums tend to have an organizing theme.

SE: Sure, I think they always have had. Starting with Guitar Town, I convinced myself that I could make country records that were art and get on the charts. Dwight Yoakam and a few other people were doing that. George Jones said around that time, “We worked our butts off to keep from being called hillbillies and Dwight Yoakam and Steve Earle fucked that up in six months!” We wore it as a badge of honor.

I think I pissed Robert Christgau off. He was one of the first people to call us “New Traditionalists” and I never claimed to be that. I claimed to be a hillbilly singer at that moment. But I never hid where I came from. I was very adamant that my teachers were Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, who was actually a folk singer.

My whole group of people are post-Dylan, but, more importantly in our immediate environment of Nashville, post-Kris Kristofferson songwriters. We were one foot in the country mainstream and one foot not. And I thought, “I did do it!” I had a No. 1 country album. I pulled it off from ground zero. Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings did it with the outlaw thing, but they had already had some success.

Mickey Newbury is at the heart of it all. He was trying really hard to be taken seriously as an artist, and it was hard to do. He had a couple of hits, and one really big one with the First Edition—they were both from Houston and came to Nashville, bouncing back and forth together. Newbury was Townes’ first publisher and that’s how he got his publishing deal. It’s like how Paul Simon is the last Tin Pan Alley songwriter, but he had one foot in the Greenwich Village thing because of when he came along. No matter what you think about him—I teach him in my songwriting course because he can rhyme consonants—he’s one of the baddest motherfuckers I’ve ever seen. He’s also really interesting and really important, just by virtue of when he came along.

MJ: You’ve had a very consistent output, almost an album per year for the last dozen years.

SE: What else would I do? I don’t take drugs anymore. I don’t drink. I’d fish more if I lived someplace else, but I don’t. I love to fish with a fly rod, but it’s not worth living in Montana or Idaho or New Zealand for that matter, cause I’d go kinda nuts. I need to live in New York. It’s the cave of the sleeping sharks: They used to think that sharks didn’t sleep, but it turns out they found a cave off the coast of Mexico where the sharks found a current, and they just turn their heads toward the current and the oxygen comes to them. That’s what New York’s like: The oxygen comes to you. If I get my wings clipped and I can’t travel anymore, this is where I want to be.

MJ: Lot’s of creative people seem to be struggling here.

SE: Because of the money?

MJ: Yeah, and the drainage of culture from that.

SE: I don’t think there’s drainage of the culture. I think it’s just hard. The culture isn’t just the artist sitting around bitching about how great the old era was. The Nation does a cruise to raise money—I’ve done it two or three times as a musical guest. You host a table every night and usually people are disappointed to be with me, rather than, you know, Rachel Maddow. But there was a guy at our table one night. His name was Erving Wolf and he was 94 years old. He asked where we lived, and we said the Village. He said, “Oh, the Village, I lived there in 1922.” Allison said, “Wow, it must have been really cool then!” He goes, “Ah, we lived there in ’22, and everybody said, ‘You shoulda lived here 10 years ago when it was really the Village!'”

People ask me why I don’t live in Brooklyn and I say, “I didn’t wait until I was 50 to move to New York to live in Brooklyn!” It’s one of those things. I’m a New Yorker—I think I’ve earned that now. Patti Smith says I’m a New Yorker, so you know, that counts.

MJ: On the back cover of some of your early records, it says, “recorded digitally on a Mitsubishi.”

SE: I had no choice because Jimmy Bowen was a proponent of digital recording, and he ran MCA Nashville. That was Bowen’s deal with Mitsubishi that got him the machines for free: He had to record on the Mitsubishi machines. It was a hustle.

I didn’t know any better. I’d made one analog record, which came out as Early Tracks, and it sounded really good. Ray Kennedy, a friend of mine from before jail, was way into analog. I went over to his place to make some demos and realized that when I made The Hard Way I had wanted that record to sound like a Faces record or something, but it was so clean—everything in its proper place. That was the people I was working for, and the format I was working in. Those digital records sound the way they sound. It’s not terrible. And I’m not Steve Albini—I think he’s a fucking idiot about that shit.

MJ: You were really tight with Van Zandt, but I’ve heard you saying that his albums felt overproduced.

SE: I don’t think Townes ever made a great record. The closest he came was a record he meant to call Seven Come Eleven. And there’s about half of The Late Great Townes Van Zandt that I love. None of it I hate, but the earlier records have moments that are just painful to listen to. You know, he didn’t put up any kind of fight for it. I do understand it, because I sometimes didn’t put that much time into what my records sounded like. I did pay attention to the arrangements.

I know what my next record’s gonna be. I made the decision to make a blues record but I was writing other songs, and they have to have a home eventually. I just decided, well, maybe I’ll just make a country record. And by country record I mean what the record after Guitar Town might have been like if Jimmy Bowen hadn’t pissed me off.

I’ve never denied that the tension between us shoved me off into another direction. I ran off with a girl who had just signed Guns ‘n Roses. I spent a lot of time in LA. The time that I spent in England influenced me even more. I met the Pogues, and Billy Duffy and I were running around a bit in those days. I was a big Cult fan. He was a fan of ours too; he came out to our shows. I think “She Sells Sanctuary” is one of the best singles I’ve ever heard. That to me is like some Beatles singles and Monkees records, something that still bounces around my head from time to time.

I’m really kind of hard for people to get a handle on, because I come from the ’80s, but I was 31 when Guitar Town came out, so I really come from the ’70s. This next record will sound closer to Waylon’s Honky Tonk Heroes than it will probably anything else. We’ll see. There’s about half a record that already exists.

MJ: You keep a very busy touring schedule. Do you still experience alone-ness when you are around your band and your audience?

SE: Traveling with a band when you’re the boss, there’s not as much camaraderie as you’d think—especially if you’re sober. It’s one of those things. I used to travel with the band—Star coaches with the bedroom in the back—and me and Alison and the baby on that bus, and the band in another bus. I couldn’t really afford it, but it was the way we had to travel, trying to keep a family together on the road. As soon as Alison was gone, I went back to one bus. It’s extended the life of my touring drastically because it’s half the money.

MJ: Does being on the road also have a nourishing aspect for you?

SE: It’s part of the process. Guy Clark told me when I was 19, “Songs aren’t finished until you play them for the people.” As songwriters, were all into getting our songs cut, but all of us wanted to play for audiences. What I was part of was essentially a salon. We played songs for our publishers, but we didn’t really give a fuck about what they thought. I cared about what happened when me, Guy Clark, Dave Loggins, Mickey Newbury, Steve Young, sometimes maybe even Neil Young, were sitting in a circle passing a guitar. That’s what I cared about. When I impressed that audience, I felt like I had something.

In Close Contact is an independent documentary project on music, musicians, and creativity. Visit InCloseContact.com for extended interviews and more photography.