University of Texas Press

In 1991, Toni Tipton-Martin was riding high: She had just been named the first black food editor at a big metro daily, Cleveland’s Plain Dealer. While in Dallas for a conference, she nabbed an invite to a cocktail party at a swank hotel. She approached the venue “really feeling excited and privileged” until “the doors to the ballroom opened—and someone asked me to get them a drink.” To some of us, being mistaken for a waitress might seem like a trivial misunderstanding, but for Tipton-Martin it evoked the legacy of black servitude in the United States. She spent the rest of the conference in her hotel room.

Her mortification prompted something positive, though: She began looking into the written history of female African American cooks. It seemed scant at first—the literature on Southern food frequently failed to acknowledge them. Back in the 1800s, for instance, when white women began recording their family food traditions, they took credit for their slaves’ handiwork. “You owned Sally, you owned her recipe,” Tipton-Martin reflected on an episode of the podcast Gravy.

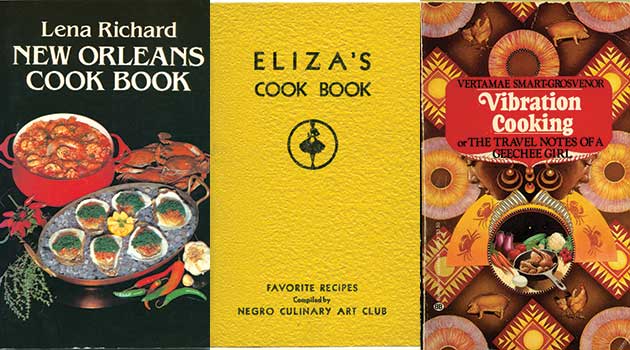

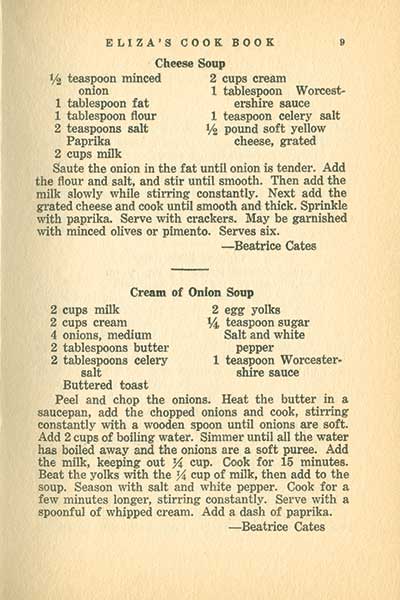

But black chefs eventually began self-publishing their own cookbooks, and Tipton-Martin has collected nearly 300 of them. There’s a sophisticated 1930s guide from the Los Angeles Negro Culinary Arts Club featuring new ingredients like oleo/margarine and Jell-O, a book by a radical 1970s chef who espoused using brown and black cookware, and a popular tome by Lena Richard on New Orleans cuisine—which Houghton Mifflin republished in 1940, but removed her name and portrait from the cover.

On the rare occasions that black chefs were credited, Tipton-Martin discovered, they were often portrayed as mammies “working out of a natural instinct or with some kind of voodoo mysterious magic,” she told me. Sure, they sometimes relied on quirky methods (measuring out ingredients by comparing their weights to that of an egg or a walnut) and folksy language (“putting vegetables up for the winter,” a.k.a. fermenting), but compare their acumen to the requirements of any culinary school syllabus, Tipton-Martin says, and you can start to “see the depth of knowledge” these chefs possessed.

In late 2009, Tipton-Martin’s research culminated in The Jemima Code, a blog and touring exhibition intended to shine “a spotlight on America’s invisible black cooks,” many of whom were skilled project managers, entrepreneurs, and creative masterminds. Now she’s made The Jemima Code the title of an appetizing new book out today from University of Texas Press, bursting with illustrations, how-tos, jingles, and rare archival photographs. Tipton-Martin, who’s twice been invited to the White House as a guest of the first lady, is already at work on a sequel, a collection of 500 recipes. She calls it The Joy of African American Cooking.