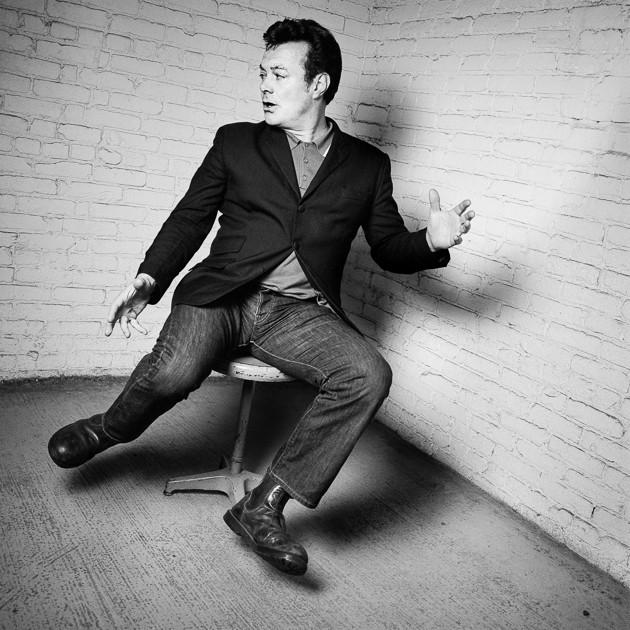

Making something real of an often-appropriated and mythologized musical style like soul or R&B is no easy task, but James Hunter has a unique ability to express himself through the sounds of the era, not just imitate them—and he only seems to get better at it over time. Hunter, 53, has been whittling away at the essence of these musical forms since his early 20s, when he migrated to London from his hometown of Colchester, England.

Hunter started off as the leader of Howlin’ Wilf and the Vee Jays, which played mostly covers and developed a fervent local following. In the mid-’90s he caught the attention of Van Morrison, who invited Hunter to join his band as a guitarist and back-up singer. As Hunter came into his own as a songwriter, Morrison made a guest appearance on Hunter’s 1996 debut album, Believe What I Say.

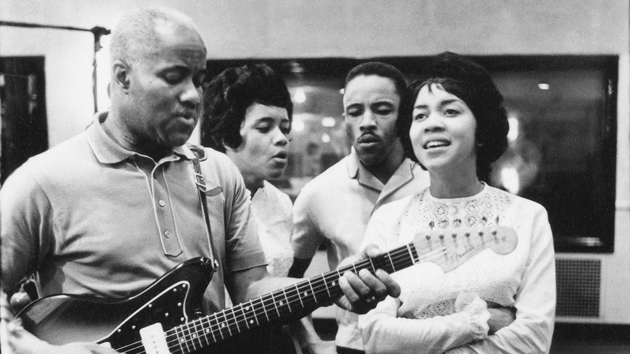

Hunter’s sound is rooted in the early soul era of the late 1950s and early 1960s—think Sam Cooke, Ray Charles, The Drifters, Bobby ‘Blue’ Bland—when pop, blues, gospel, jazz, and rock were all intermingling. He plays a game of refinement, borrowing sounds and themes from the past and giving them a contemporary perspective through his musical craft and wry humor.

Out last week, Hunter’s latest, Hold on! (read our review here), is his first release through Brooklyn’s Daptone Records, and the second produced with label co-founder Gabriel Roth.

Mother Jones: In the past, you’ve expressed the opinion that some soul artists invest the music with a mystique it doesn’t warrant.

James Hunter: That’s right, people are too reverential towards it. If you are approaching the music with more reverence than the original guys invested into it, you are effectively doing it a disservice. There’s this requirement of “authenticity,” whereas these fellas were just making records they just hoped would sell. And the people who were writing them were just doing it out of the love of it. It’s when you are trying to make something that is “authentic” as opposed to real—people who appreciate music for the wrong reasons tend to compartmentalize stuff. They’re too in love with the categories and filing. It’s too much nuts and bolts and not enough spirit.

MJ: Apart from music of the ’50s and ’60s, do you have significant influences that might not be so apparent to the listener?

JH: I get influenced by stuff that isn’t even music. With a screenwriter like Billy Wilder, you’ll hear him recycle a joke in slightly different form from something at the beginning of a film, reusing it with an ironic twist later on. It’s a songwriting trick that I stole—a way of hammering something out.

MJ: Your songs have a kind of universal appeal. Is that a deliberate effort on your part?

JH: Because I’m English, I try not to make any purely American references, because I want to limit how much I’m pretending to be American. I’ve broken that rule sometimes, when something rhymes and just works well then fuck it, but I’m trying to be as neutral as possible so I could be from anywhere. I’m conscious enough that how I’m singing is not my own accent. Van Morrison has got those particular broad vowel sounds; he can sing in his own accent and do something in an American idiom convincingly. But if I sang the way I talk it would sound like “Tommy Steele sings Muddy Waters!”

MJ: Making music that sounds like it could have been made 60 years ago, how do you find newness in it?

JH: If I have any claim to originality, I do it by investing my own personality into it, so it’s coming from a slightly more sardonic, English point of view. Mine is a little bit more inspired by Spike Milligan. It’s a slightly different style but people over here get it.

MJ: “Something’s Calling” stands out as an example of a song that puts a new twist on an old theme. It might have been written as a gospel tune in the style of the Soul Stirrers, but here it seems like it’s about something more personal and existential.

JH: It is a bit sneaky of me, but it is open to that religious interpretation. It’s vague enough that it doesn’t have to be strictly autobiographical, but it is based on that time I was about to move to London from Colchester and the job that wasn’t taking me anywhere. It was a poignant thing; I was shaking off the dust and making a start at something, a better life. The day I left, I visited three people who had been holding me down. I meant to tell each of them what I thought of them, but none of them were there. It was also the day of my grandmother’s funeral, so it was bittersweet. I was 23.

MJ: I gather you worked for the railroad before pursuing music.

JH: I joined in 1979. On my 17th birthday I got the letter giving that I had passed the interview and I’d be going to Liverpool Street station to have the medical. It’s just like the army. They do the “cough and drop” where the doctor grabs you and tells you to cough. I’d never experienced that before or since. I didn’t have a hernia so they accepted me for the next seven years.

MJ: What that life like?

JH: Not bad. I knew I wasn’t where I wanted to end up. I was an apprentice and I knew I wasn’t going to pass all the stuff they put me through. They put me with the maintenance unit at Clacton-on-Sea, these three old guys in their 60s, knocking retirement age. They were the kind of old men I wanted to be like when I grew up.

MJ: So those weren’t the three you went to tell off?

JH: No! That was a girlfriend, an ex-flatmate, and the landlord—who cowardly sent his wife to give me back my deposit. The railroad guys were my heroes. Like most old carrot crunchers they could be daft in their own ways.

MJ: “Carrot cruncher?”

JH: That’s like a country bumpkin, or a bit of a hayseed. It was very much that carrot cruncher thing, always asking, “How you getting on, boy?”

MJ: How did your music career in London come together?

JH: I had a little trio in Colchester, in Essex, 50 miles northeast of London. Howlin’ Wilf and, I think, the Detours. We stole “the Detours” from what The Who used to be called early on. I sent a demo to Ted Carroll at Ace Records—they did a lot of blues reissues. He didn’t do anything with it but he played it for Dot and Tony. They were a couple, she played the guitar and he played the double bass. They had a band called the Hatchet Men that had all split up and they got in touch with me and asked if I fancied going to London. So that was quite exciting, I thought it might be a step to something, so I’d knock off from the railway, pack my suitcase and nip up to London on the train, stay with them over the weekend. We’d cobble together a little busking set of old obscure blues songs and go out with a couple of battery powered amps. We got such a following that we got invited indoors to play, and suddenly we had a full diary. The new version of the band was called Howlin’ Wilf and the Vee Jays.

MJ: Compared to your last record, Minute By Minute, the new one has more space and quiet moments. Does this reflect any personal changes, or changes in your approach?

JH: I was just trying to make it better—more personal, maybe a bit more grown up, less pastiche-y. My absolute favorite song I’ve ever written is “This Is Where We Came In.” It’s a nudge at younger listeners, cause at one time you could go into a cinema halfway through a film and then stay through and pick up where you left off. That was an analogy that was begging to be used to describe a relationship that was going tits up.

Andy Kingslow, the keyboard player, put this really classy cocktail-y piano on the recording. As an afterthought, he evoked the precurtain music of the Saturday morning pictures with the organ intro. It’s a little cheeky; I wanted to rub people’s noses in the analogy. It could have been cheesy, but it worked.

MJ: For Hold On!, I notice you’re going by “the James Hunter Six,” rather than simply your own name.

JH: I wanted them included, and I wanted us to sound more like a unit. If people didn’t know us already I didn’t want them to expect a singer-songwriter. We had tried to think of a name ages ago and anything you think of sounds as corny as hell. It’s like a tattoo; once you’ve done it you’re stuck with it. We got the idea in a dressing room in San Diego, there were some album covers on the wall and we saw “Ramsey Lewis Trio” and realized, “Fuck, why not just name the band after how many there are of us?” People ask, “why the James Hunter Six?” and I pull their leg and say, “Well, stylistically we fall somewhere between the Dave Clark Five and the John Barry Seven.”

MJ: From what I’ve read, you enjoy being on the road, and prefer to take a few years between records.

JH: It’s a lifestyle that suits me because I do like having a lot of time off. But it does work against me. I am quite a slow writer. I can only work under pressure; I wait until the last minute. It’s a fear of anything that smacks of academia. For me, hearing the term “apply yourself” was like a crucifix to Bella Lugosi’s Dracula. “Ahhh, it burns!” Some people can write 10 songs before breakfast. But sometimes you can see where the lack of effort went.

This profile is part of In Close Contact, an independently produced series highlighting leading creative musicians.