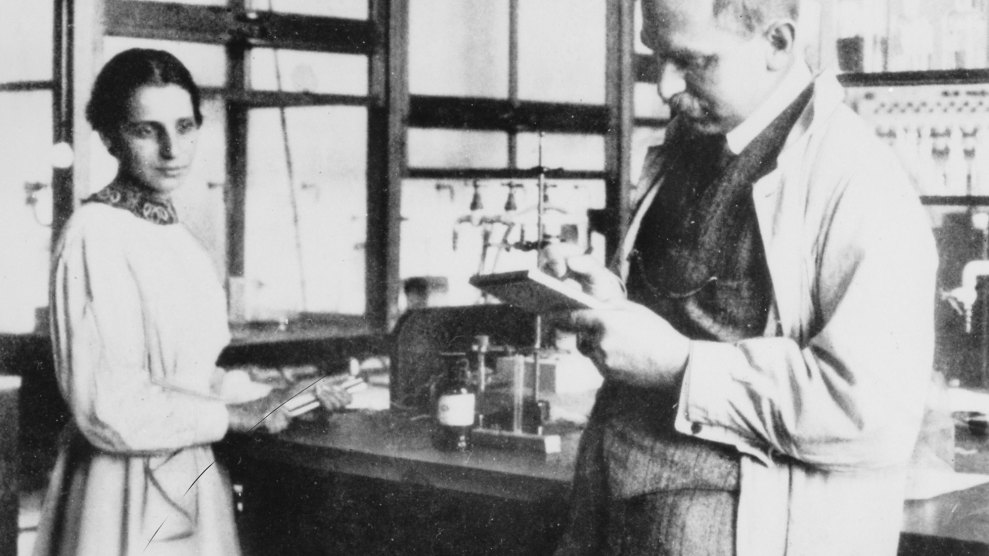

Lise Meitner and Otto Hahn, Germany, 1913.Smithsonian Institution Archives

In Donald Trump’s 2011 book Time to Get Tough: Making America #1 Again, the president-to-be made an astonishing claim: Lady Gaga likely owed her international fame to none other than…Donald Trump. “She became a big star and maybe she became a star because I put her on the Miss Universe pageant,” he wrote. “It’s very possible, who knows what would have happened without it, because she caused a sensation.”

The problem goes beyond Trump, of course. Women, especially women of color, are routinely denied credit for their ideas, creativity, genius, and success (not to mention they’re paid less than men for full-time work). So, in honor of Women’s History Month, I’ve put together this woefully incomplete timeline of the lowlights:

- Paleolithic era

- Pre-European cave paintings are attributed to male hunters up until 2013, when an anthropologist shows that hand tracings found alongside the art at 10 famous sites were likely done by women.

- 12th c.

- “Trota of Salerno” authors a gynecology handbook, On the Sufferings of Women. For centuries, scholars falsely assume Trota was a man.

- 1806

- At the close of the Lewis and Clark expedition, Sacagawea is paid nothing for her year and a half of work as an interpreter and guide. Her husband, a white trapper who married her after she was taken captive, receives $500.

- 1818

- Mary Shelley publishes Frankenstein anonymously. Her husband pens the preface and people assume he was behind it.

- 1843

- Mathematician Ada Lovelace shows how Charles Babbage’s Analytical Engine (a theoretical computer) could be induced to perform complex math. Her contribution, considered the first software, was dismissed by many male historians: “It is no exaggeration to say that she was a manic-depressive with the most amazing delusions.”

Ada Lovelace/Wikimedia

Ada Lovelace/Wikimedia - 1840s

- The Brontë sisters take male pen names. “Authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice,” notes Charlotte, author of Jane Eyre. Mary Ann Evans later writes Middlemarch as George Eliot, probably to avoid “being treated as ‘just’ a female writer,” one expert notes.

- 1859

- After 10 years working with engineers to design signal flares, Martha Coston is listed as “administratrix” on the patent. Her long-dead husband is listed as the inventor.

- 1888

- Ellen Eglin sells the rights to the clothes wringer she invented to an agent. The invention brings “great financial success” to the buyer, who paid her $18. “If it was known that a negro woman patented the invention, white ladies would not buy the wringer,” she explains.

- 1904

- Elizabeth Magie creates The Landlord’s Game. Player Charles Darrow later patents a modified version: Monopoly.

Jens Buettner/DPA via ZUMA

Jens Buettner/DPA via ZUMA - 1905

- Nettie Stevens publishes a paper establishing that chromosomes, not environmental factors or diet, determine the sex of an organism. The same year, E.B. Wilson, a more celebrated male colleague, independently arrives at a similar conclusion and gets most of the credit.

- 1908

- Henrietta Leavitt, a “human computer” at the Harvard College Observatory, discovers the period-luminosity relationship (the brighter the star, the more slowly it appears to pulse). Her work is key to calculating interstellar distances, but male astronomers snag the credit—Leavitt dies in obscurity.

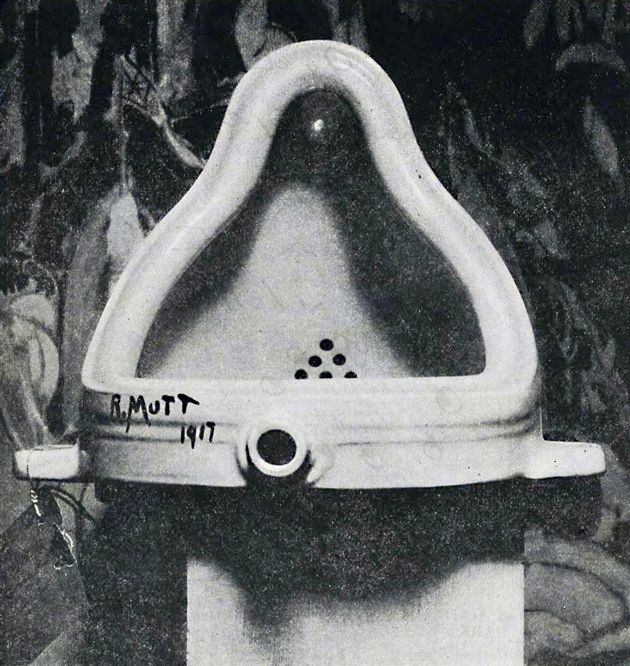

- 1917

- “Fountain” (a urinal) is submitted to a New York City exhibition. Art critics later cite evidence that Marcel Duchamp’s infamous piece was sent to him by a “female friend”—possibly Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven—under the pseudonym R. Mutt.

Alfred Stieglitz/Wikimedia

Alfred Stieglitz/Wikimedia - 1938

- Based on observations by her German colleague Otto Hahn, Jewish physicist Lise Meitner works out the first model of nuclear fission. Hahn publishes the work and accepts the Nobel Prize, portraying Meitner as his assistant. A new element, Meitnerium, is named in her honor—60 years later.

- 1939

- The British government hires Joan Clarke as a codebreaker on Alan Turing’s team during World War II. Years later, she is immortalized on screen by Kiera Knightly—but remembered mainly for her doomed engagement with Turing.

- 1946

- “Government and scientific men” hold a dinner gala to celebrate the first electronic computer, the New York Times reports. None of the women responsible for programming it are invited.

- 1952

- R&B singer Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton is the first to record “Hound Dog,” a country blues tune written especially for her. Elvis Presley’s vastly more famous version is later featured by the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame as “the most illustrative example of the white appropriation of African-American music.”

- 1953

- James Watson and Francis Crick’s discovery of DNA’s structure hinges on Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray diffraction studies, but she’s excluded from their Nobel Prize-winning paper. “Rosy might have been quite stunning had she taken even a mild interest in clothes,” Watson notes in his memoir, The Double Helix.

Rosalind Franklin Cold Spring Laboratory Harbor Archives

Rosalind Franklin Cold Spring Laboratory Harbor Archives - 1957

- The Nobel Committee for Physics passes over Chien-Shiung Wu—a Manhattan Project scientist who designed an experiment that overturned the so-called parity law of physics—in favor of the two male scientists who had recruited her to work on the topic.

- 1961

- Male NASA scientists rely on math whiz Katherine Johnson and her fellow Hidden Figures to send men into space. “Woe unto thee if they shall make thee a computer,” a NASA newsletter preached to female employees. “For the Project Engineer will take credit for whatsoever thou doth that is clever and full of glory.”

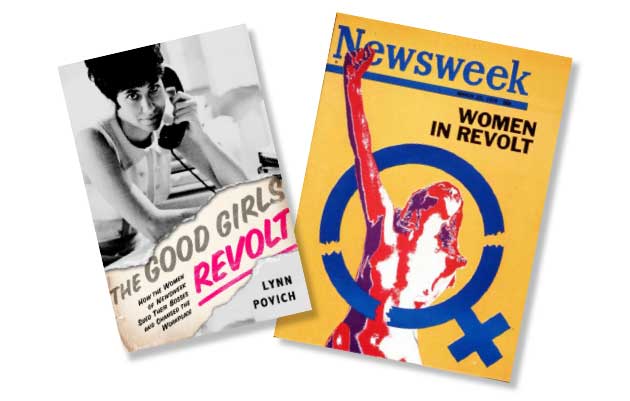

- 1970

- Forty-six female researchers sue Newsweek, alleging that male writers and editors took all the credit for their efforts.

- 1986

- Margaret Keane sues ex-husband Walter Keane, claiming she created the paintings of big-eyed children and animals that made him famous. The case drags on for many years. By the time Margaret prevails, Walter is too broke to pay the award.

- 1993

- Historian Margaret Rossiter coins the phrase “Matilda effect” (after a suffragette who claimed a woman was behind Eli Whitney’s cotton gin) to refer to the undervaluing of women’s contributions in science.

- 2006

- Truman Capote’s letter praising a draft of his childhood friend Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird turns up, putting to rest decades of speculation (which Capote made little attempt to dispel) that he was the true author.

- 2007

- M.I.A. vents about male reporters crediting her ex, who contributed to a few songs on her debut album, as its mastermind: “I just find it kind of insulting that I can’t have any ideas on my own because I’m a female.”

- 2008

- After know-nothing guys try to school essayist Rebecca Solnit on topics in which she happens to be an expert, she pens an essay titled “Men Explain Things to Me.” The word “mansplain” enters the lexicon.

- 2014

- Whitney Wolfe sues Tinder, claiming a fellow exec stripped away her title because “having a young female co-founder makes the company seem like a joke.” The case is settled privately.

- 2015

- In a study of the tenure process at top economics programs, Harvard Ph.D. student Heather Sarsons finds that women aren’t getting credit for papers they co-author with men.

- 2016

- Just after Hungarian swimmer Katinka Hosszú shatters a world record at the Rio Olympics, NBC cuts to her volatile coach/husband in the stands. “And there’s the man responsible!” a male commentator proclaims.

Hosszú and hubby. Hosszú: David Gray/Reuters; Husband: Dominic Ebenbichler/Reuters/Zuma

Hosszú and hubby. Hosszú: David Gray/Reuters; Husband: Dominic Ebenbichler/Reuters/Zuma - 2016

- Kanye West raps, “I feel like me and Taylor [Swift] might still have sex. Why? I made that bitch famous. (God damn) I made that bitch famous.”

This article has been updated.