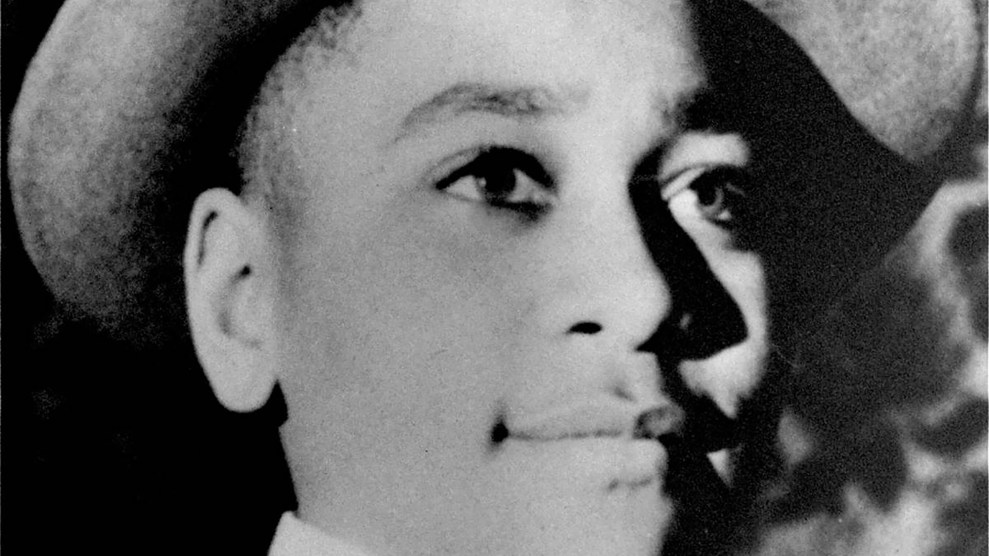

Portia Wiggins Portraiture

When Kwame Alexander talks, you can sense something irrepressible just under the surface—laughter, maybe, or swagger—dying to burst forth. It’s the same vibe the 12-year-old protagonist of his Newbery Medal-winning 2014 novel-in-verse, The Crossover, exudes on the basketball court. Alexander, 48, was a baller himself: “I was No. 1 on the tennis team,” he says. “I beat everybody.”

Raised in New York City and later Virginia by literary types—publisher dad, English teacher mom—Alexander has produced two dozen titles to date, from a collection of Tupac essays he edited to poetry volumes and children’s picture books. Solo, out August 1, is a young-adult novel co-written with the children’s author and editor Mary Rand Hess. Using poems as their vehicle, Alexander and Hess follow the travails of 17-year-old Blade Morrison, the scion of a profligate Los Angeles rock star, as he stumbles along a path of self-discovery that takes him to Ghana—to the same remote village, in fact, where Alexander co-founded a real-life nonprofit that provides books, teacher training, and literacy programs for children.

Mother Jones: Many Americans these days think of poems as something to pull out for birthdays, weddings, and funerals. Were you surprised The Crossover was such a slam dunk?

Kwame Alexander: I wasn’t. I spent the last 20 to 30 years reciting poetry in schools or performing at open mics in churches and universities. I got firsthand feedback in the form of standing ovations, or fourth-graders asking me to autograph their hands, or people in church saying, “Amen. Hallelujah!” I courted my girlfriend back in 1998 by writing her a poem a day for a year—and she married me!

MJ: She’d better have!

KA: Right? So I knew poetry worked. I figured I was gonna be the guy to remind us that we all love it.

MJ: Solo could be a hit, too. It’s hard to put down. It actually kind of made me cry.

KA: Thank you, man. I’ve been so unsure about this novel because Young Adult is such a different space than Middle Grade. You’ve got to be a little bit edgier—you gotta get deep.

MJ: I actually thought my son would reject The Crossover because of the poetic form, but he ended up liking it. Do you hear that a lot?

KA: All the time. We expect kids to go straight from Shel Silverstein to William Shakespeare. There needs to be a bridge of relatable, fun, rhythmic verse that gets kids to cross over, so to speak, so they can appreciate Mary Oliver and Naomi Shihab Nye and Langston Hughes and e. e. Cummings.

MJ: Are you a musician?

KA: I don’t play, but I consider myself a music aficionado. I listen to instrumental jazz when I’m writing. Before I’m headed to do a reading or a talk or a keynote, I’m listening to hip-hop or bossanova to get me in that cool mindset. If I’m on the beach, on a road trip, maybe I’m listening to some country music.

MJ: Wait, country?

KA: Yeah, man! [Laughs.] Country music is a story. I’m a storyteller.

MJ: Do you think hip-hop has helped make poetry cool again?

KA: Or poetry helped make hip-hop an art form. Poetry and hip-hop are cousins. They’re trying to do different things. If you put some Lil Wayne lyrics down on a page, am I gonna be able to read that and say, “Oh, wow, there’s some sort of transformation that’s happening in my soul?” I think the answer is no. But I don’t think that makes hip-hop any less than poetry.

MJ: Judging from Solo, you also know a bit about rock and roll.

KA: In the mid-to-late ’80s, man, I was a tennis star. The soundtrack for my tennis tournaments and road trips with my buddies was Genesis and the Police and Tears for Fears—that whole ’80s rock and new wave stuff really spoke to us. I knew I wanted to pay tribute to that part of my life, the love and the loss and everything that I experienced during those teenage years.

MJ: Did your black friends give you shit about the tennis and the rock music?

KA: Of course! But I had been raised to be confident in my own space. I could move in and out of circles. [The poet] Nikki Giovanni says, “You gotta dance naked on the floor, and people will watch you or they’ll go home, but you gotta be confident in it.” If I was playing tennis, I was wearing my high-top Chuck Taylors and my corduroy shorts and my cutoff T-shirts while everyone else had white shorts, white shirts, white socks, white sneakers. You gotta be who you are wherever you are. I think that’s what Blade is trying to discover.

MJ: Blade’s rocker dad is named Rutherford Morrison. Is that an amalgam of Mike Rutherford and Jim Morrison?

KA: Exactly.

MJ: Mike Rutherford stole my name for his stupid band, Mike and the Mechanics. I may never forgive him.

KA: There you go! We went through so many names that sort of epitomized rock, and Morrison was the one that had the right syllabic count. Mary came up with Rutherford.

MJ: I’ll have to have a talk with her. In any case, Blade and his sister, Storm, are both named after comic book characters. Were you a comic geek, too?

KA: I wasn’t. But I am working on Rebound, the prequel to The Crossover. The main character is the father from The Crossover when he was 12. He’s a Fantastic Four and a Black Panther fanatic. So I’ve been immersed.

MJ: You come from a bookish family. Give me the dinner table scene.

KA: Literature was at the forefront of our dinner table conversation, our vacations, our chores—my father owned a publishing company and I was in charge of licking envelopes with catalogs to send out. Every Thanksgiving, we traveled back to New York City and my father held a book fair in Harlem the day after. We all worked this fair, selling books. We went to the same Chinese restaurant every Thanksgiving. As the oldest kid, who was forced to read books like Pedagogy of the Oppressed at age 11, I hated books! All these books ended up being good, but I wanted nothing to do with it. The thing that brought me back to a love of literature was I was nerdy and shy when it came to girls, so I began to write poems for them. All of a sudden I was the cool guy.

MJ: How did your dad make you read these books?

KA: If your father, who is known for carrying around a belt, told you to read a book, you went and did it. I’ve never spanked my kid—I think because in my household you were afraid. If you did something wrong and got caught, you were getting spanked.

MJ: So your muse was the belt.

KA: Exactly. But during my middle and high school years it was the music—the classic rock, the gospel my parents sometimes played, and eventually jazz. I came home from college and discovered in my attic three crates of jazz: Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Ornette Coleman, Miles Davis—records my father had purchased when he was my age or a bit older. I discovered that he used to listen to “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” and John Coltrane’s “Naima.” That was when I sort of fell in love with my dad.

MJ: Yeah, I did notice a sort of “coming to dad” element in your books.

KA: One of my editors says I have daddy issues because I’m always trying to get rid of the dads, or they’re not functioning at a very positive level. My dad likes to say he deserves royalties!

MJ: What kinds of books did your father publish?

KA: Boring educational tomes that no kid wants to read. Books about history and education, and books that were gonna change the world in a way that he saw fit. Now I go back and look at them, and at the work I’m doing in schools and in Ghana, and I realize I am essentially taking what my father did to another level. How ironic is that?

MJ: When you first went to Ghana, were you kind of thinking, “Hmm, this would make a good setting?”

KA: No. In fact, in the first draft, [that part of Solo] took place in Kenya. Neither one of us had been to Kenya, but I knew Ghana intimately. I’d been hiking there. I’d been in the village trying to build a library. I’d been in the rainforest. Mary said, “Well, Kwame, maybe we’re not in Kenya. Maybe we’re in Ghana.” I sort of pinched myself, like, “Why didn’t you think of this before?”

MJ: So, how does one write this kind of book with another person?

KA: We outline it completely. We know exactly what the beginning, middle, and end is. We write a couple poems and try to understand the style. We may write the same poem together, or we may go, “You go do that poem; I’m gonna do this one.” Months later, we’ve got hundreds of poems and we lay them all out on the floor and rearrange them. So the first draft is just like putting a puzzle together. Mary and I are very similar in our writing, and where we aren’t, we can channel each other.

MJ: I wanted to touch on race again. The Crossover is really about just being a kid, not about being a black kid. But those things can be hard to separate.

KA: There are places and spaces for black writers to write about race as a central thing. It’s important. We’re still dealing with the remnants of slavery. We’re still dealing with racism on a daily basis. For me, I choose to write books about black people where we are normal. I was raised to believe that I deserve to be in a room just like anybody else. I try to write books like that.

MJ: So what’s next for you, besides the Crossover prequel?

KA: Solo was dealing with rock. The next book, Swing, will be dealing with jazz. To complete the trilogy of my tribute to the music of my life, the third book will probably have something to do with hip-hop. [Laughs.] Or country.