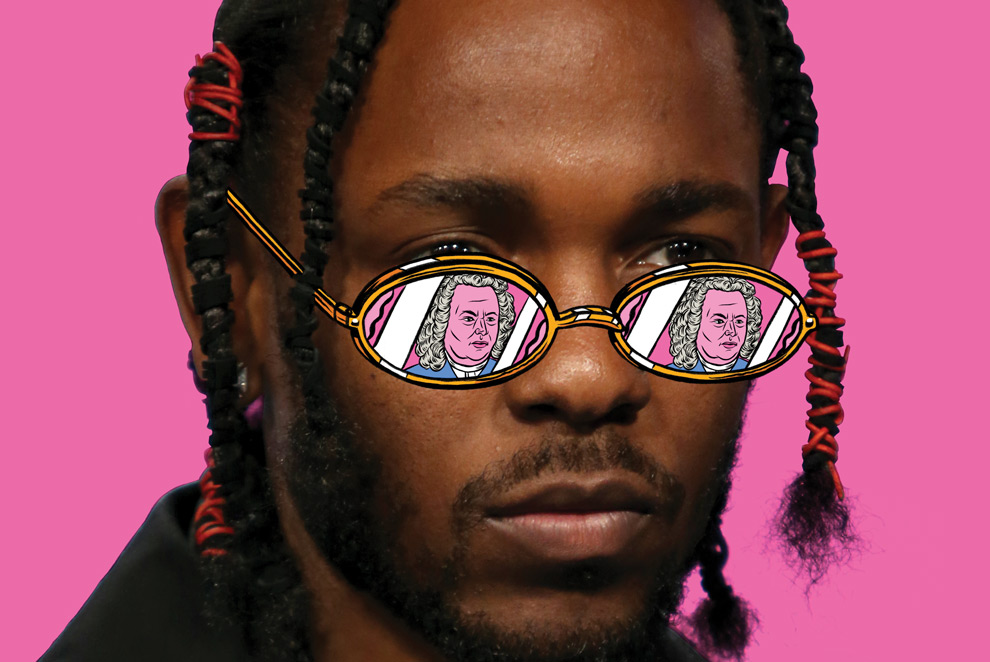

On March 15, 2015, Kendrick Lamar released To Pimp a Butterfly, a jazz-infused exploration of black culture, racial inequality, and personal transformation that went on to win several Grammys. Early the next morning in Sacramento, California, 33-year-old Cole Cuchna sat in a rocking chair calming his day-old daughter, Mabel. As the sky lightened, he donned his headphones to take in Lamar’s new work. “It was a very romantic moment,” he remembers.

The album made a deep initial impression, but Cuchna, who had a degree in composing, felt that he, as “a white kid from the suburbs,” couldn’t fully access Lamar’s storytelling without some serious music-nerd analysis: “I couldn’t just listen to it casually and understand everything he was trying to say.” Could the theoretical scrutiny his professors had used to deconstruct Gregorian chants and Mozart symphonies be applied to hip-hop? Cuchna decided to find out. The following year, between work shifts at a coffee company, he began recording Dissect, a podcast that unpacks in incredible detail the artistry, historical and cultural allusions, and symbolism in rap music. His goal: “to bridge the gap between classical and contemporary.” Over three seasons, Dissect has built a solid listener base, garnering critical acclaim and spots on iTunes charts and various best-podcast lists. Last year, deeming Cuchna a “rare talent,” Spotify acquired Dissect as part of its original podcast portfolio. In December, critic Wesley Morris included it in the New York Times’ “Five Great Podcasts From 2018,” likening Cuchna to a “scuba artist” deep-diving for “little bits of treasure.” Dissect, Morris wrote, “thrives as an achievement of contemplative audio.”

Hip-hop has surpassed rock as America’s pop music of choice, yet academic study of the genre is nascent and negative stereotypes persist—Cuchna’s Beatles-loving father once called it “rap crap.” But Cuchna knew superstars like Kanye West and Lamar, who last year became the first rapper to win a Pulitzer Prize, would “define our generation in 100 different ways.” He wanted to make rap “accessible to my mom, in a language that she’s going to understand. I wanted to make my mom a fan of Kendrick Lamar.”

When I meet Cuchna at Temple Coffee Roasters, the sleek Sacramento coffeehouse where he worked for six years, he’s dressed in a black T-shirt and sweats and spotless white sneakers, laces untied. His brown hair sticks up and swooshes dramatically to one side, and his voice is so soft I have to lean in to catch it. Cuchna spends roughly 400 hours doing research to produce a full season of the show, each of which focuses on a single album. So far, he’s deconstructed works by Lamar, West, and Frank Ocean, typically just one song per episode. His analysis follows the album’s narrative arc, but he’ll dig deeper, say, to provide a refresher on white flight and help listeners understand Lamar’s Compton childhood. He is quick to deploy his classical music knowledge: You might listen to West’s “Power” and intuit its message about the perils of fame, but without Cuchna’s nudge you probably wouldn’t notice it’s written in a key that the Great Composers often used to illustrate “the heroic struggle,” including in brooding works such as Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C Minor or Brahms’ Symphony No. 1.

Cuchna is hardly the first podcaster to tackle rap. Lawrence Ware, co-director of Oklahoma State University’s Center for Africana Studies, cites the late Reggie Ossé, whose Combat Jack Show was “a treasure trove of hip-hop interviews.” There’s also The Realness and Gimlet Media’s Mogul, which center on rap personalities. But Dissect is unique, Ware says, in that it focuses more on the music than on the artists.

It’s also the rare show in which rap is analyzed by a lone white guy. That worried Cuchna at first, “but the more I thought about it, it was like, ‘Well, why not someone like me?’” In the season-one finale, he pushed the point further: “I don’t think we get anywhere as a culture if we’re afraid to confront issues because they’re difficult or we feel like they don’t apply to us. In fact, because they’re issues understood primarily by the people they affect is perhaps one reason why they perpetuate.”

Ware, who is black, appreciates that Dissect touches on race, and he wishes Cuchna would go further. “Maybe invite someone on,” he suggests. But “there’s a certain generation of people who don’t look at hip-hop as being rigorous or having any kind of depth to it, so I do think there’s value in making work that’s geared toward a white audience.” Although, Ware adds, “I don’t know if Kendrick Lamar would want his work analyzed for the sake of white audiences.”

Cuchna says Lamar’s label is aware of Dissect, but it hasn’t offered any feedback. He did hear from a rep for Ocean, born Christopher Edwin Breaux. “I pronounced his given name wrong, so he corrected me,” Cuchna says. “He didn’t have anything bad to say—so that was cool. Reassuring.”

Season four, which launches this week, focuses on an artist Cuchna has yet to announce—thought he’s been dropping clues on social media for the past few weeks. In the fall, he tided his fans over with a miniseason on The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, whose gifted 23-year-old creator tackled motherhood, spirituality, and relationships before disappearing from the limelight. Hill’s album is two decades old but continues to reverberate, and Cuchna enjoyed exploring its influence on today’s musicians. Great art “gives and gives and gives,” he reminded his listeners. “But you have to make yourself available to it.”