If you buy a book using a Bookshop link on this page, a small share of the proceeds supports our journalism.

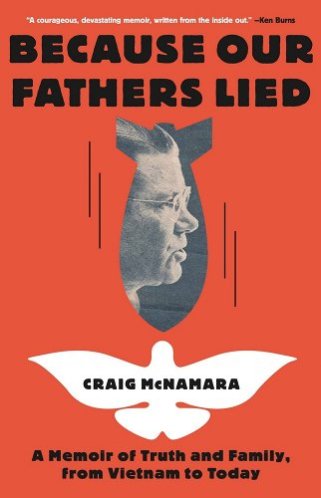

Because Our Fathers Lied: A Memoir of Truth and Family, from Vietnam to Today

Nonfiction Lots of people have daddy issues. But it’s not often you come across a memoir written by someone whose father was the primary architect of the Vietnam War. Craig McNamara, a walnut farmer, sustainable agricultural leader, and son of John F. Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, writes a brutal and intimate story about a son confronting his father’s legacy of destruction—a single relationship as unresolved as the infamous war. When I first picked up the book, I didn’t quite know what to expect. To my surprise, I learned that in addition to tearing apart a nation, Robert McNamara’s lies about Vietnam shattered the heart of his young, impressionable son. This book holds little in common with Errol Morris’ famous, Oscar-winning documentary, The Fog of War—Craig McNamara is much gentler in writing about being haunted by his father’s legacy, and trying to build a far-removed one of his own through farming. Instead, we find a Robert McNamara who loved the outdoors and took his son hiking and skiing; a family man who tried not to bring his work home to his children, but ultimately failed. The younger McNamara anchors the book in his father’s inability to have an honest conversation about his involvement in the war and why he couldn’t offer an apology. “Loyalty, for him, surpassed good judgment,” writes Craig about his father’s silent allegiance to the Kennedy and Johnson administrations and the values of the American empire. “It might have surpassed any other moral principle.” —Ruqaiyah Zarook

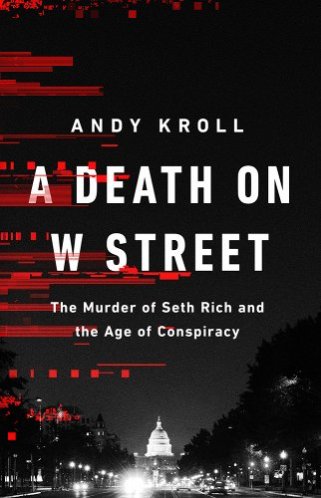

A Death on W Street: The Murder of Seth Rich and the Age of Conspiracy

Nonfiction Before QAnon. Before Donald Trump’s Big Lie. Before Proud Boys stormed the Capitol—there was the murder of Seth Rich. A young Democratic National Committee staffer, Rich died in 2016 during what was almost certainly a botched armed robbery. But conspiracy theorists insisted his death had been ordered by the Clintons as part of a plot to frame the Russian government for hacking Democratic emails. These falsehoods would set the stage for years of political chaos. “Seth’s story is a skeleton key to the past half-decade in America,” writes Kroll. It’s the story of “how the failure to find those who committed that crime opened a void into which the gullible, the dangerous, and the deluded poured their misbegotten ideas and political ambitions and so created a maelstrom of deception that undermined every important institution in the country.” Kroll, a MoJo alum, shows how deep dysfunction—in the DC police department, in conservative media, in the legal system—helped turn a violent tragedy into a lie that blanketed Fox News. But for all his insights into what Seth Rich has meant to American politics, Kroll never loses sight of Seth Rich the person, and the friends and family from whom he was taken. —Jeremy Schulman

Dirtbag, Massachusetts: A Confessional

Nonfiction “My parents were married when they had me, just to different people.” So begins Fitzgerald’s “confessional,” a lucid memoir brimming with stoic New Englanders, seedy bars, stifling Catholicism, and somehow, despite all that, so much heart. Fitzgerald grew up poor in a dysfunctional household, spending a childhood stint at a homeless shelter before being carted out to a depressed rural town. He took solace in books, landing a scholarship at a prep school where he leaned into his role as local ruffian amid a sea of elite super jocks (Ritalin proved the great equalizer). Eventually, he made his way to San Francisco, where the biker bar Zeitgeist became his church, and supported a budding literary career (full disclosure: I worked on the Rumpus with Fitzgerald back in the day) with jobs as varied as bouncer and Kink.com model. The essays in this collection are entertaining and brisk, but it’s their warmth and vulnerability that sets them apart. Fitzgerald holds a magnifying glass up to his own weaknesses, his tangos with toxic masculinity and his troubled relationship with his family, to reveal a generous soul who inspires camaraderie wherever he lands. —Maddie Oatman

Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else)

Nonfiction In a matter of years, Black Lives Matter went from being considered a fringe rallying cry to a hashtag and slogan that significant corporations weren’t afraid to associate with. Despite this, nothing for Black people, or any other nonwhite races, has gotten materially better. In Elite Capture, Georgetown assistant philosophy professor Táíwò deftly guides us through how, by isolating identity from class, the masters of society can pay lip service to racial and social injustice without ever doing anything that would actually resolve it. In what is maybe the clearest articulation of this “elite capture” phenomenon that I’ve read, Táíwò provides the start of a roadmap that can hopefully lead us beyond it. —Ali Breland

A Heart That Works

Nonfiction If you know anything about Delaney, you know that he is an American comedian and a recovering alcoholic who happens to be the star of the much-acclaimed Amazon prime series Catastrophe. He’s also the author of the 2013 memoir Mother. Wife. Sister. Human. Warrior. Falcon. Yardstick. Turban. Cabbage. Perhaps you also know that his happy and successful life—okay he struggled with depression but his was a deliriously fulfilling marriage—was demolished when his third son, Henry, an incandescent little boy, died in 2018 at only 2 and a half years old of a brain tumor after enduring nearly unimaginable suffering for more than half his life. There is always the question of when one knows the agonizing conclusion to a story: Why voluntarily subject oneself to this kind of pain when life tends to dish it out so lavishly anyway? In this case, the reason is that in Delaney’s remarkable memoir of that harrowing time, you will encounter a singular way of processing a grief so immense and an injustice so incalculable that it defies imagining. Someone told him that the London tabloid the Daily Mail “had called and were aware that I had a son…being treated for a brain tumor and wanted to know if I wished to comment. I told him to please tell the Daily Mail that if they printed anything about my son, I would kill the reporter and any editors who approved it, and then sit down in a puddle of their blood and wait for the police to come. No article ran.” When his father-in-law said through his own tears, “I wish it was me instead of Henry,” Delaney replied, “We do, too, Richard.” The immediacy of the love, the grief, the rage at the sheer breathtaking injustice of it all, recounted with humor and heart, makes this story, dare I say it, inspirational. Throughout are the scenes of a sturdy and tender marriage that refuses to be broken by the shit sandwich its participants have been served. Read this book not for Delaney’s celebrity nor even for a good cry but for something more: a rare picture of the family coping with the worst thing that can happen, with love and humor, all illuminated by a kind of costly grace. —Marianne Szegedy-Maszak

The High Sierra: A Love Story

Nonfiction Robinson, a two-time Hugo Award winner, is one of the world’s premier science-fiction writers. Or so I’m told; I’ve never read any of the novels he’s famous for, but I picked up his ode to the high peaks and passes of California on a whim after a week hiking somewhere else—hoping, in that familiar post-vacation comedown, to mentally extend my stay just a little while longer. Robinson’s book is part atlas and part memoir, a deep map that intersperses historical snapshots and geology lessons with stories from more than half a century ambling over rocks and snowfields. There is a personal story here, about friendship and family and growing up, but it is fundamentally just a dude writing about his hikes and how much they rule. This is not one of those books you can’t put down; it’s a book you’ll be tempted to close in a hurry—to get to the nearest trailhead yourself. —Tim Murphy

I Dream of Dinner (So You Don’t Have To)

Nonfiction It might seem a touch overblown to credit a cookbook with easing postpartum depression. But after spending months chained to a nursing chair, the opportunity to properly prepare a meal—and maybe even enjoy its contents—felt absurdly exhilarating. It was even more thrilling because I’m not a natural cook; I blend soggy leftover nachos as a topping on fresh tortilla chips; I didn’t know what a whisk was until some years after college, thanks to a friend, a former pastry chef at Jean-Georges. But with her debut cookbook—accessible but carrying hints of a more sophisticated life beyond baby spit-up—Slagle opened a sense of potential that didn’t feel remotely available to me at a moment in life when I really needed it. Consider the recipe Slagle affectionately refers to as a “stunt,” “Rice with Lots of Herbs & Seeds.” At once exceedingly easy to whip up—I personally skip the coconut chips—yet surprisingly complex thanks to a dash of lime and fish sauce, the dish is lovely either on its own or paired with leftover salmon. I eventually bailed on breastfeeding, a decision that took months to make peace with. But I take pleasure in knowing that years from now, when he’s ready to eat what I eat, I’ll be ready with some delightful recipes. —Inae Oh

I’m Glad My Mom Died

Nonfiction If you’re someone lucky enough to have a good relationship with your parents, you’ll probably be shocked by the title of this book. “How could anyone ever say this about their mother?” you’ll whisper to yourself. But, honestly, by the time you get to the end of this memoir, you’ll be glad that McCurdy’s mom died, too. McCurdy is a 30-year-old retired actress-turned-writer who rose to fame on a Nickelodeon sitcom as a teen. In this book, she details the abuse she endured from her mother, starting from her childhood living in poverty. Her mother, who had her own unfulfilled dreams of Hollywood stardom, forced McCurdy into performing regularly at only 6 years old. By the tender age of 11, McCurdy became the breadwinner for her entire family. After securing a leading role on the hit show iCarly as the fried-chicken-loving tomboy, Sam Puckett, she was thrust from obscurity into sudden stardom. She starred in six seasons of the show all while battling an eating disorder encouraged by her own mom, who consistently violated her boundaries, forcing her to share everything from her emails to the entirety of her income. She even showered McCurdy until she was 16 and made her succumb to full-body inspections. After her mother lost her battle to cancer in 2013, McCurdy was left adrift. The one person she lived her entire life to please was gone and now she had to deal with the complicated emotions on her own. This book isn’t your average fluffy celebrity tell-all. McCurdy explores grief, parental abuse, identity, mental illness, the dark sides of child acting, and religion all with a biting wit and raw vulnerability. If there’s only one book you read in 2023, make it this one. —Arianna Coghill

Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism

Nonfiction Yes, it is like the title. And tolerance levels will vary for a book with sentences like “The plasticity of nature does not negate its characteristics as a natural substratum of labour.” But Saito’s book is revelatory. Its first sentence—“The world is on fire.”—is more indicative of how jarring and powerful its ideas are, and how forcefully Saito argues for taking seriously radical new imaginings of Marxism, eco-socialism, and the taboo thought that we must stop growing. His argument is complicated and also simple. What if we misunderstood Marx’s ideas on the need to dominate nature? What if, instead, Marx was something like an eco-socialist? Saito reads Marx’s environmental work, often ignored, and finds a path forward. He can sound a bit like any scholar who wants sure footing here—aha, he seems to say, I’ve discovered what Marx really thought. Still, he does bridge a gap. Twentieth-century Communism was often described as the gray, materialist, smoke-filled image of dour Sovietism. Environmentalism was the verdant, sometimes spiritual, hope of freedom and trees. Can a socialist argue for something in tune with nature, especially amid climate catastrophe? The world makes us feel we must. But at the moment, green technology marches forward as the most acceptable answer to climate change among the powerful. Saito’s clear-eyedness amid that is a balm. “Today capital is no longer productive,” he writes, “but rather destructive and threatens human existence.” For all its discussions of Harvey, neo-Malthusianism, non-Cartesian dualism, and the Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (often called MEGA), this is a book about how we live our lives. It questions basic ideas of what is meaningful and what is desired. Do we really enjoy all that capitalism has offered? How do we actually want to exist? I was reminded of Svetlana Alexievich’s Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, an oral history about the lived reality of the fall of the USSR. “Happiness is here, huh?” one person rants to Alexievich of life after the fall. “Sure, there’s salami and bananas. We’re rolling around in shit and eating foreign food. Instead of a Motherland, we live in a huge supermarket. If this is freedom, I don’t need it.” —Jacob Rosenberg

No Choice: The Destruction of Roe v. Wade and the Fight to Protect a Fundamental American Right

Nonfiction This was a year saturated with writing about abortion, and rightly so, as it was also a year when the politics of abortion changed in the United States forever. So you might be forgiven for feeling like you’ve hit your abortion quota for a while. But the first sentence of this debut book by former Mother Jones staff reporter Becca Andrews tells you that it won’t be like anything else you’ve read on the subject. “For twenty-three years, I was vehemently antiabortion,” she writes. “As my world grew, as I learned to let in more people who were unlike me, I could no longer find reasons to justify my worldview as it had been formed.” What follows is a deeply empathetic examination of the place of abortion in society, starting in ancient Greece (did you know Socrates’ mother was a midwife and abortion provider?) and running through the fall of Roe. With heart-wrenching and powerful stories of abortion and family-building at its center, No Choice ultimately seeks to draw readers into the world that changed Andrews’ mind about reproductive choice. —Nina Liss-Schultz

The Storm Is Here: An American Crucible

Nonfiction There’s only one person, as far as I know, who was an eyewitness to the torching of Minneapolis’ Third Police Precinct in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder and the sacking of the United States Capitol in the attempted coup of January 6. We’re lucky that it was a writer and reporter of the caliber of Mogelson. As the New Yorker’s war correspondent for the United States’ wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria, Mogelson was troubled by the “disconnect between our careless belligerence abroad and peace and prosperity at home.” So in 2020, he returned to his home country to survey how the chickens had come home to roost. Building on his magazine dispatches, the book is something of a dystopian travelog, as Mogelson takes us from the anti-lockdown protests at the Michigan statehouse to the George Floyd uprising in Minneapolis, from anti-fascists clashing with Proud Boys on the streets of Portland and Washington, DC, all the way to the floor of the Senate chamber on January 6. The scenes are so vivid you can practically hear the QAnon Shaman roar. Mogelson doesn’t hide that he finds some grievances to be far more legitimate than others, but he also has a sincere and deeply probing interest in what is happening in the hearts and minds of everyone who took to the streets in 2020. “Most of the Americans I’d met in 2020, no matter their politics, had one thing in common,” he writes. “A diminished faith in the government as a reliable authority, whether to administer justice or to ensure their safety.” In this book, Mogelson has crafted the definitive first draft of history of a year that will live in infamy, no matter what comes next. —Eamon Whalen

Strangers to Ourselves: Unsettled Minds and the Stories That Make Us

Nonfiction To read Aviv, a staff writer at the New Yorker, is to always wonder whether any other writer could have pulled off her dexterity and perceptive ability to navigate impossibly complex subjects—only to arrive at the conclusion that probably not. It’s no different with her debut book, Strangers to Ourselves, a thought-provoking and profound examination of the ways people experience mental health illness and the narratives they tell themselves (and are told) to make sense of their struggles. “There are stories that save us, and stories that trap us,” writes Aviv, recounting her hospitalization for anorexia at the age of 6 and her later journey with an antidepressant, “and in the midst of an illness it can be very hard to know which is which.” As Aviv reflects on her own childhood diagnosis and how her life could have turned out differently had her identity been claimed by it (what she describes as a “sense of narrow escape” from the illness becoming a “career”), she introduces us to five other people facing often conflicting frameworks and remedies for the pain afflicting their minds. Among them are a doctor torn between psychoanalysis and psychopharmacology; an Indian woman whose religious awakening was interpreted as schizophrenia; and a Black mother caught in a cycle of poverty whose feeling that “white people are out to get me” led her to jump off a bridge with her twins. Drawing from journals and interviews with family members, Aviv gives us not a single, definitive narrative about the mind, but instead several portraits “searching for the gap between people’s experiences and the stories that organize their suffering, sometimes defining the course of their lives.” —Isabela Dias

There Are No Accidents: The Deadly Rise of Injury and Disaster—Who Profits and Who Pays the Price

Nonfiction “At Three Mile Island, the decision to purchase a fragile reactor lined up with a routine shutdown lined up with a locked cooling system lined up with a control board that made it look like an open valve was closed—a tightly coupled, complex system.” Oh boy, as someone who grew up in the figurative shadow of TMI, I sure did not like that section one bit. That’s just one incident Singer lays out in her 250-page investigation into the complex web of government, corporate, and social systems that make us accept everything from the massive devastation of the Deepwater Horizon explosion to the pedestrian death at our local crosswalk as an “accident.” If you’re reading this in Mother Jones you’re likely already aware of the ways in which corporations evade responsibility every day for the deaths and injuries of workers and people on their watch—but even this thinking is too small, argues Singer. Around 170,000 people die from “accidents” each year that we know well how to prevent. As the climate changes and the gig economy expands, that number is only likely to grow. “Find the systems that led to an accident—the big and the small, the personal and the systemic, the design of the road and the racism of vehicular homicide prosecution as well. This is the only way to prevent accidents,” Singer challenges us. It’s an energetic, engaging read that will challenge your perception of our everyday world—basically the kind of reporting I want to do when I grow up. If you don’t have time to read Singer’s book (and even if you do), my colleague Abigail Weinberg has a great interview with the author here. —Emily Hofstaedter

What’s for Dessert: Simple Recipes for Dessert People

Nonfiction I am not, admittedly, a neutral newcomer to Saffitz’s work, but a bona fide fangirl. I’ve seen all of her YouTube videos and even used a recipe from her debut, Dessert Person, to make my homemade funfetti wedding cake. So it’s maybe no surprise that I quickly fell in love with her newest book, but I’d argue it’d be hard for any dessert lover not to. Compared with Dessert Person, the recipes in What’s for Dessert? feel much easier to approach on a whim, which is exactly the point. “Not only can every person find a dessert here to suit their tastes,” Saffitz writes in the introduction, “they can find one to match the time and energy they want to invest as well.” I found this to be exactly true one night when I was suddenly overwhelmed with a need for chocolate cake. Rather than rushing to the corner store for some plastic-wrapped sugar bomb to stifle the craving, I opened up What’s for Dessert? and in less than 45 minutes whipped up its Molten Chocolate Olive Oil Cakes, which were easy to make and decadent to eat. Saffitz’s recipes are accompanied by gorgeous, colorful photography that makes What’s for Dessert? feel more like a coffee table art book than a traditional cookbook, which is for the best, because as much as I’ve been enjoying it, I hardly want to put it away on a shelf. —Ruth Murai

When The Moon Turns to Blood: Lori Vallow, Chad Daybell, and a Story of Murder, Wild Faith, and End Times

Nonfiction In June 2020, I took my stir-crazy teenager and fled the claustrophobic DC lockdown for my home state of Utah, where malls were open and the vistas were wide. Even as the pandemic raged, the biggest local news stories there had been about something else entirely: two missing children in nearby Idaho. There’d been vigils for the kids and increasingly bizarre reports emerging about their mother, Lori Vallow Daybell, and her new husband, Chad Daybell, the author of a series of apocalyptic Mormon novels who some people followed like a prophet. We were driving through Idaho the day police found human remains on the Daybell property. The kids had been located. As we road-tripped through my old stomping grounds, the explosive story followed us for the next few weeks, as news accounts revealed disturbing details about the Daybells’ religious beliefs and the possible murders of their previous spouses. Eventually we went back to DC and I forgot all about the Daybells—until this summer, when Sottile published this gripping book that filled in all the details we’d missed. Host of the excellent podcast Bundyville, Sottile had previously taken a deep dive into the story of Cliven Bundy and his family, the Mormon ranchers whose beef with the federal government led to an armed standoff in Nevada in 2014 and a 41-day armed takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon in 2016. She unearthed fresh details about the Bundys’ unorthodox Mormon belief system and showed how it influenced their opposition to the federal government. The Daybell story felt like an extension of that work. Sottile deftly ties together a true crime narrative with one about a faith subculture that flourishes in both Utah and Idaho Mormon communities, despite the church’s efforts to squelch it. If you liked Jon Krakauer’s Under the Banner of Heaven, you’ll definitely want to pick up When the Moon Turns to Blood, which I found even more riveting. —Stephanie Mencimer

The Wild World of Barney Bubbles: Graphic Design and the Art of Music

Nonfiction As outrageous, brilliant, and impactful as his work was, Barney Bubbles (real name: Colin Fulcher) was something of a modest man. From the 1960s into the ’80s, the British graphic artist designed for cutting edge bands and record labels, often uncredited. You probably know his work, most likely on Elvis Costello’s early records. From the fantastical packaging of space rock pioneers Hawkwind to his stark, piercing covers for the earliest punk bands, created in collaboration with Stiff Records (Costello, The Damned, Wreckless Eric, DEVO, among many others), Bubbles’ impact not just on record design but on punk and rock music more broadly still reverberates like a long ringing guitar chord. In The Wild World of Barney Bubbles, Gorman pulls the curtain back on Bubbles’ process, the method to this madness. Heavily illustrated with paste-ups, works in progress, rough drafts of logos and posters, and unusual pieces (a square Ian Dury and the Blockheads watch!), it’s a fun, inspiring insight into a great designer who often lets his work speak for him, and for itself. —Mark Murrmann

Disorientation

Fiction You know that feeling in your 20s where you’re not quite sure what to do with your life, so you consider grad school? Well, in this biting satire of the world of higher academia, the main character is pursuing her PhD and still feeling lost. Ingrid is not quite connecting with the Chinese poet she’s doing her thesis on, which her white adviser insisted she take on as a topic. Despite not being Asian, he is the premier scholar for this poet and feels that Ingrid may be able to take over for him one day. After Ingrid discovers a note in her school’s archive that leads to questions about the famed Chinese poet, she launches an investigation and discovers things are not as they appear (think Rachel Dolezal). Aside from the rave reviews in major publications, Disorientation is also loved by Malala Yousafzai, whose production company is co-developing it for a movie. Between Ingrid’s boyfriend’s obsession with Asian culture, her dive into protests, and her adviser’s descent into full MAGA culture, this book is nothing short of one of the best examinations of grad programs and what it’s like to be a person of color in them. Chou would know—she was a Rona Jaffe Graduate Fellow at NYU in 2017. —Angelica Cabral

Sea of Tranquility

Fiction Readers familiar with Mandel’s previous work (she’s best known for Station Eleven and The Glass Hotel) will recognize in Sea of Tranquility her ability to describe grief and terror so quietly it almost feels serene. You might also recognize Mandel herself in the character of Olive, who like the author has written a hugely successful novel about a pandemic. Unlike Mandel, Olive was born and raised on the moon. Sea of Tranquility spans centuries and space, with characters unknown to each other but somehow connected. Even if the book did not explicitly mention Covid, which it does, it would be clear to anyone who has lived through this time that it was written in the pandemic’s shadow as the characters grapple with questions about what makes any of us real to each other, and to ourselves. When the world is falling apart, when it is ending, when it is just simply not what you imagined it to be—what makes a life worth living? This is the kind of book that is hard to stop thinking about when you’re finished with it. Even in the months since I last put it down, as the details of character and setting have faded from my memory, I have thought over and over again about Mandel’s description of a spaceship leaving Earth: “The atmosphere turned thin and blue, the blue shaded into indigo, and then—it was like slipping through the skin of a bubble—there was black space.” —R.M.

The Swimmers

Fiction I am a swimmer and my mom has dementia, so I felt like Otsuka had written this book specifically for my demographic of one. “If you swim for long enough you no longer know where your own body ends and the water begins and there is no boundary between you and the world,” she writes. “It’s nirvana.” In the delightfully funny first half of the book, Otsuka describes life at a pool, where the regulars have “real lives” above ground as “overeaters, underachievers, dog walkers, cross-dressers, compulsive knitters (Just one more row), secret hoarders, minor poets, trailing spouses, twins, vegans, ‘Mom.’ Above ground, they may be “ungainly and awkward,” but in the water, “we are only one of three things: fast-lane people, medium-lane people, or the slow.” There’s lane-two sidestroker Irene or dogged paddler Lilian in lane three, and those to watch out for, like the “aggressive lappers, determined thrashers, oblivious backstrokers, stealthy submariners, middle-aged men who insist upon speeding up the moment they sense they are about to be overtaken by a woman, tailgaters, lane Nazis, arm flailers, ankle yankers.” And then there’s Alice, a retired lab technician with dementia who can be spotted above ground with her hair disheveled and her pants on inside out. But “even though she may not remember the combination to her locker or where she put her towel, the moment she slips into the water she knows what to do,” the narrator observes. The swimmers paddle along contentedly in this chlorinated community until a crack appears in the bottom of the pool and things fall apart, especially for Alice and her prodigal daughter, who realizes only too late that her mother is slipping away. The Swimmers is a hard book to pigeonhole but at a slim 176 pages, it is a luminous and utterly original gem, and you don’t have to swim to appreciate its loveliness. —S.M.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow

Fiction I am a sucker for writing about writers, and films about filmmakers: stories about craft, about the blurred lines between art and life and what it takes out of a person to make something beautiful. Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is a vast, stunning story about storytellers. The storytellers at the heart of the book, Sadie Green and Sam Masur, are video game designers, and masters at their craft. But like many other successful artists, Sam and Sadie are nearly ruined by the work and their compulsion to continue it, no matter the cost to their minds, bodies, or, more importantly, friendship. This book is about love—romantic, platonic, unrequited, unconditional. Like a gamer glued to a screen all night, I couldn’t keep the promises I kept making to myself as I read this book that I’d put it down after “just one more chapter.” You don’t need to be into video games for this story to connect with you, but don’t be surprised if Zevin’s vivid and exciting writing has you picking up some game controllers yourself. —R.M.

America (1986)

Fiction About 20 years before the sparsely populated rural American heartland became the endpoint of a hajj for people who went to Dartmouth and then got jobs writing about politics in the national press corps, French philosopher Baudrillard did his own trip across America. Unlike national politics writers, Baudrillard spends equal time traversing the American arterial highway system as he does in LA and New York. A verbose, goofy French academic cavorting around America via its expansive freeways is funny, but it’s also instructive. Without realizing it, in 1986 Baudrillard gives an incisive snapshot of a moment in America that will define the next several decades—it is a loop that we never seem to escape. He, for example, describes an America embarrassed by a Vietnam War that has shaken its dominant status as global hegemon and that is desperate to reclaim it. Baudrillard also eerily writes about “The latest obsessions of American public opinion: the sexual abuse of children.” He doesn’t provide clear answers as to how we break any of this, but he does give us a way to look at it with fresh, foreign eyes, which is probably helpful. At the very least, it’s extremely fun. —A.B.

Cloud Cuckoo Land (2021)

Fiction I can’t remember if it was after finishing Matt Bell’s Appleseed or midway through Sequoia Nagamatsu’s How High We Go in the Dark that I noticed the trend: authors braiding together three or more narratives, flipping between characters from long ago, from a contemporary setting, and from far into the future. The structure appeared again and again in my fiction reading list, so much so that I began to think of it as the narrative flavor of the year. There it was in The Immortal King Rao, Vauhini Vara’s tale of an Indian farmer’s humble beginning, his rise to tech superstardom, and his granddaughter’s plight in a futuristic society. Emily St. John Mandel played with the format in Sea of Tranquility, bouncing us between early 20th century Vancouver, the pandemic-pocked 2100s, and the dark-skied space colonies of the distant future. But in my eyes, it was Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land that best harnessed this device. Doerr sticks with three eras: the 15th-century Byzantine Empire, present-day Idaho, and a spaceship in the 22nd century, threading them together with a codex that survives the ages. His characters, including an ambitious seamstress in Constantinople and an autistic teen who takes up with ecoterrorists, are fierce, focused, and inimitable, their predicaments urgent, making each narrative feel grounded and full of life. We are always flitting between nostalgia and our hopes and fears for the future. So why did 2021 and 2022’s speculative novelists turn en masse to this structure? I’m not sure reading so many novels with this triptych composition led me to any revelations. The constant hurtling through various eras was often disorienting and became somewhat tiresome after the third book. In the end, it was Doerr’s fully realized characters, the people who jumped off the page, who most held my attention, no matter their location in the space-time continuum. —M.O.

Daniels’ Running Formula, Fourth Edition (2021)

Nonfiction Running is the dumbest sport. All you have to do is move forward, repeatedly—at length. At least, that’s how it begins. Then, as you try to get better, as you train for races, the process becomes complex: paces, shoes, form, workouts, plans, gear. For about three or four years, I’ve run basically every day. I would log between 60 to 80 miles a week—throwing in track workouts, fartleks, long runs—but never really tried to race. Then, this year, I tried to be a serious runner. I bought this book, considered a bible of running, to follow a plan for once. The original book dates back to 1998. Daniels was famously dubbed the “world’s greatest coach” for a time. His formulas—paraded out here in half-scientific charts—are most well-known for popularizing a method of training focused on VO2Max. Let’s pause there. Do you even want me to explain that? Do you want to be trapped in a written version of a conversation with a person training for a marathon? Probably not. The reason I am recommending this book is because reading it in full I came back to my first conclusion about running: This is stupid. And that’s great. Humans are sad creatures, in need of games and hope. Let me follow a therapist’s advice, sorry: I am a stupid creature, in need of games and hope. All the tables, charts, and schematics to make the process of running faster into something scientific made me laugh out loud. They were genuinely helpful, sure. But, also, the idea of me—some guy trying to run a fast 5K who is not an athlete—using a graph to determine “lactate threshold” really tickled me. I got to play-act like an Olympian. I would keep a spreadsheet and obsess over paces. Then, in the end, I went back to my original thoughts about running—it’s just one foot in front of the other. The idea I had tried so hard to make it not this silly activity (and, in the races, just a painful shitshow) delighted me. Real dumb. Real fun. —J.R.

Gilgamesh: A New Translation of the Ancient Epic (2021)

Fiction Although the Mesopotamian epic about the adventures of a 17-foot-tall ancient king is one of the oldest written narratives in existence, we haven’t been reading it for very long. The first cuneiform tablets were translated in the late 19th century, and the text continues to change as researchers decipher new fragments. In 2018, researchers discovered that Gilgamesh’s buddy Enkidu, a wild man who becomes civilized after a marathon sex fest with a woman named Shamhat, had actually been going at it for twice as long as previously believed. (Two weeks, not seven nights.) The edition I read, a 2021 translation by Helle that was recommended by Defector, had long sections that were left blank—placeholders for the passages we haven’t found yet, and might never. But there is an echo between the story in Gilgamesh and the story of Gilgamesh, that I find deeply moving. The epic is, in part, about the power of knowledge. Gilgamesh, we are told, traveled to the end of the Earth following the death of his friend, and “brought home a story, from before the Flood.” (Yes, that flood.) He found some ancient kernel of knowledge—a lesson, incidentally, about immortality, from Utnapishtim, the Flood’s lone male survivor—and gave it a new life. And by engaging with the epic several millennia after it was lost, you can too. —T.M.

The Hare With Amber Eyes: A Hidden Inheritance (2010)

Nonfiction I’m not breaking any new ground here: De Waal’s bestselling memoir of the Ephrussi family—as told through a collection of Japanese netsuke that had passed through the generations into his possession—was such a magnificent achievement that it inspired its own exhibition, more than a decade later, at the Jewish Museum in New York. A ceramicist by trade, de Waal treats every page of his family’s story—from the birth of their fortune in Odessa, to the lives they made in Vienna and Paris, to their exodus to the UK and North America before and during the Second World War—with the thoughtfulness and care of a master craftsman. If you’ve read it, you already know all of this, of course. But if you haven’t, don’t waste another year. —T.M.

It Came From Something Awful: How a Toxic Troll Army Accidentally Memed Donald Trump into Office (2019)

Nonfiction I picked up this book expecting it to be a chore. Other contemporary histories of online phenomena I had read in the past were mostly boring slogs of internet tedium packed into a single physical book–useful documents for posterity, but not particularly interesting. A few pages in, I realized that Beran’s book was something else completely. From the origins of the mostly forgotten but influential forum Something Awful to 4chan’s efforts to help elect Trump to the alt-right’s ascent and implosion, Beran nimbly contextualizes internet history with the actual world, blending it with intellectual influences hiding in the background that influence the decision-makers who help shape the internet. To Beran, trolls are not reductively described malcontents reacting to technology that’s breaking their brains, nor are they simply young men who have turned to wreaking havoc on the internet in response to diminishing economic opportunities. Instead, Beran helps us understand how even people who hold views not worthy of absolution can still be products of forces larger than themselves. If you want to understand internet culture and how it intersects with politics, Beran’s book is one of the most thoughtful I’ve encountered. —A.B.

John Wayne’s America (1997)

Nonfiction If you’re a fan of Wills’ 1970 masterpiece of political analysis, Nixon Agonistes: The Crisis of the Self-Made Man, you might like his lesser-known cultural biography of one of the most well-known—and mythologized—20th-century movie icons, John Wayne. You might also appreciate it if you’re a fan of Westerns and have time to read someone psychoanalyzing our obsession with celebrities. The book is thoughtful, in-depth, and deeply researched, even though Wills occasionally finds it difficult to stick to his own thesis. He demonstrates how Wayne came to represent a “figment of other people’s imaginations,” a kind of “hollow triumph” for American audiences to attach themselves to. Wayne is also entrenched in some of the most fundamental myths of modern American history through his film roles. Wills writes: “Wayne was not just one type of Western hero. He is an innocently leering ladies’ man in his B films of the thirties, a naif in Stagecoach, an obsessed adolescent in Shepherd of the Hills, a frightened cattle capitalist in Red River, a crazed racist in The Searchers, a dutiful officer in cavalry pictures, the worldly-wise elder counselor in later movies.” When he reminds readers that Americans have not yet escaped “the myth of the frontier, the mystique of the gun, the resistance to institutions,” Wills may be talking about virtually any decade in this century, and undoubtedly about the foreseeable future. —R.Z.

The Last Samurai (2000)

Fiction Very rarely is domestic fiction done just right. Maybe that’s why DeWitt’s The Last Samurai—which temporarily went out of print in 2005—is still considered a cult classic. The book is about a single mother, Sibylla, who uses Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai to provide male role models for her intelligent, fatherless boy. In turn, Ludo, the child at the center of this novel, goes on a quest to find a “benevolent male” to look up to and begins a prolific journey of self-education in the process. The best part for me was how DeWitt unabashedly embellishes her story with all kinds of heavy symbolism: from Japanese syllabaries to Icelandic sagas, hieroglyphs, German phrases, and Homeric critique, she insists on writing with an intelligent, almost snobby style that perhaps only a polyglot writer with a PhD in Classics from Oxford could weave together. As a result, this book left me irrationally giddy and inspired. It’s long, endlessly erudite, and warm, and relishes in being intertextual. It provides a timely meditation on what it means to feel closely connected to what we read and watch, and fetishizes art in all its forms. But The Last Samurai isn’t about creating or being inspired by art. It’s about consuming it in a million strange and unceremonious ways. —R.Z.

The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois (2021)

Fiction This debut novel moves back and forth in time between the story of Ailey Pearl Garfield, a Black woman coming of age at the end of the 20th century, and that of her enslaved ancestors struggling to survive on a Georgia plantation. In both worlds, the characters struggle to overcome trauma and abuse. Slowly, we see how the present mirrors the past, and how the legacy of the past lingers in the present, particularly in small-town Georgia where Ailey spends her summers and attends an HBCU. To name every theme or plotline of this book would sound like a long list of bitter vegetables the reader must swallow, including addiction, abuse, and American slavery. But the novel is layered and poignant, never obligatory; a feast of story and character from which I never grew full. I picked up Jeffers’ novel as I made my way through lists of the best books of 2021. Love Songs was better than the sum of the rest, one of the best books I have ever read. It’s no small feat to write an 800-page page-turner. A poet, Jeffers does not sacrifice craft for plot. This book is sweeping, riveting, painful to the point of tears. Despite its length, I mourned when it ended. Ailey and her ancestors stayed with me, swirling in my mind long after the last page. —Pema Levy

Our Noise: The Story of Merge Records, the Indie Label That Got Big and Stayed Small (2009)

Nonfiction Maybe selling out used to matter because bands could actually do it. When, in 1993, Entertainment Weekly wondered if Chapel Hill, North Carolina, could be the “new Seattle,” it was not only because there was a specific scene or a specific sound but because “record-company execs” felt the Pacific Northwest city had “grown passé.” A new frontier was needed; corporations hoped to mine, and export, music for kids across America from these dingy college towns. And so A&R prospectors swooped in on underlooked cities looking for rumored deposits of loud guitars hidden in basements. It was the early 1990s. Nirvana lived. Rock mattered. Remember that? Well, sadly, I don’t. I was born in 1994. I grew up in North Carolina fetishizing the idea of that Chapel Hill scene I missed, and the bands that grew out of it: Archers of Loaf, Dillon Fence, Superchunk, Polvo, Southern Culture on the Skids, Sorry About Dresden. This book offered me a glimpse of a nostalgia I didn’t earn. It partially details the Chapel Hill of that era, and the creation of the record label that defined its legacy, Merge.

In some ways, this is a business book. Co-writers Ballance and McCaughan are members of Superchunk and the founders of Merge Records, which, as the title suggests, released a series of influential bands that defined the ethos of rock music in the 1990s and 2000s: Don’t go “big.” But that makes the story they tell, with journalist John Cook, so fitting. “Indie” as a genre has always hidden its origins—economics—in plain sight. This is a book about music, but it’s also about how a series of bands, an entire generation, learned to make enough to live, create art, and give that art to people—all without “selling out.” The trick? You sell something on your own terms. Putting out your own book? Very Merge records, very “indie.” Reading it forced me to face that the Chapel Hill scene I thought I missed never existed, at least not strictly. The year before EW wrote about the “next Seattle,” Sonic Youth put out a song called “Chapel Hill.” “Too bad,” the chorus lamented, “the scene is dead.”

While living in the city during college, I put on a small variety show (read: an excuse to drink beer, tell jokes, and listen to friends’ bands) with that as the name: The Scene Is Dead. I thought it perhaps could give voice to my fear: The whole thing is over—nothing will be cool again. Reading this book helped me remember the real lesson of Merge and Chapel Hill: Get all your friends in a room and make some dumb shit together. It might be nothing, it might be embarrassing—or it might end up being the thing that, years later, some dork like me is obsessed with. As Superchunk sings: “You’ve got muscles, use them.” —J.R.

Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy (2012)

Nonfiction Written during President Barack Obama’s first term, this is very much a book of the moment in which it was conceived. Hayes produces an astute account of how America’s meritocracy morphed into an oligarchy that, as it cheated to enrich itself, brought down big businesses and shook Americans’ faith in their institutions. From Enron to the Catholic Church, from the financial collapse to the war in Iraq, the first decade of the 21st century revealed America’s elites to be cheaters and thieves; as he put it, the emperors had no clothes. Despite its 2012 publication date, the book contains the seeds of many of America’s current woes: how the age of Obama gave way to the Trump era, the disinformation crisis, and the assault on democracy itself. The failures of our elites, he writes, “prompt citizens to adopt a corrosive skepticism about the very legitimacy of the project of self-government.” If we assume all elites are cheaters, why not elect one president? On disinformation, he observed: “If the experts as a whole are discredited, we are faced with an inexhaustible supply of quackery.” Hayes then presciently cites vaccine hesitancy as an example; little could he have known that anti-vaxxers would become a large and corrosive force in American politics. It’s hard to read Hayes’ portrayal of an elite that, having been elevated as the best and brightest, now act with impunity, and not think of today’s Supreme Court. Engaging and perceptive, Twilight of the Elites brings new perspective to the turbulence of the aughts—and connects it to the problems of the present. —P.L.

When the Moon Was Ours (2016)

Fiction Since adulthood, books seldom take me to lands where I can be lost. Yet when I think of this book I am suddenly there beneath the silver blue moon, at the edge of the woods where the glass pumpkins grow and the scent of tuberose lays heavy on my skin. Miel and Sam are outsiders, terrifyingly strange and inseparable. Miel grows flowers from her wrists. Nobody knows where she came from, she just fell out of the water tower one night. Sam was born in Pakistan. He paints moons and hangs them in the forest because Miel is afraid of the dark. Only Miel knows he was born once-upon a-time as a girl. Their friendship turns to romance while Miel’s magic makes her the target of other girls who are hungry to take her power for their own. This young adulthood fantasy novel has echoes of the legend of La Llorona but also navigates love and identity, inspired by McLemore’s own relationship with her husband, who is transgender. “As teens, we feel the growing weight of questions we’ve held in our hands since we were children,” McLemore writes in her author’s note. During a time when any mention of teen queerness or sexuality seems to be under attack from the far-right, it is such a relief to have a book that gives space to ask questions. Give this novel to your teenager if they like romance and magic. Likewise, read this novel yourself with a cup of hot cocoa under a full moon while you break your own heart again with the memory of your first love. —E.H.