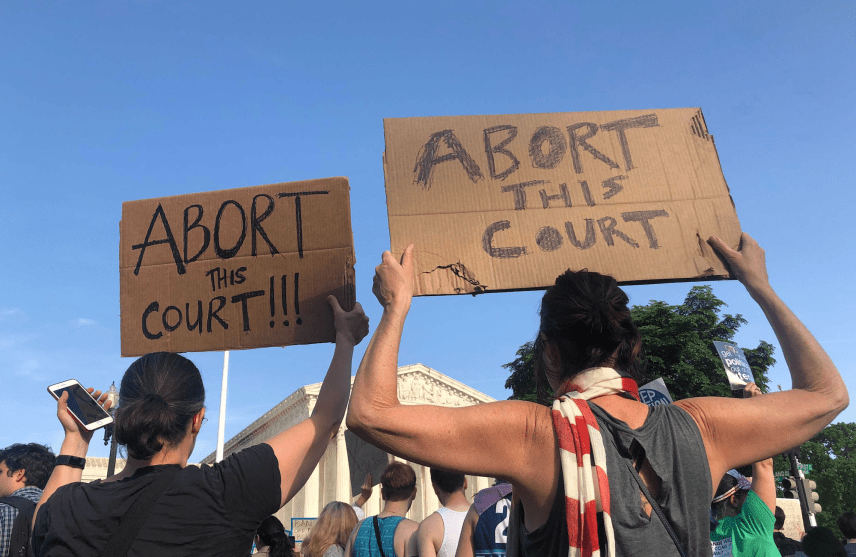

Getty

If you read the leaked draft of the Supreme Court opinion overturning Roe v. Wade, and especially if you have a uterus, you may notice several factual errors about women and pregnancy made by its author, Justice Samuel Alito. (My colleague Pema Levy, in fact, chronicles a few here.) Those errors, it turns out, may have something to do with whom Alito is citing: In all its 98 pages, the draft cites very few women.

I know because I counted. Or, at least, I tried. The opinion includes more than 75 citations from legal experts, historians, and scholars of philosophy. By my tally, just four are women. I also counted the number of times Alito cited a judge, either on the Supreme Court or lower courts. In all, he cites a judge or justice more than 90 times. Of those, just five were women.

I’d also like to point out that Alito cites himself at least six times. I repeat: The man who authored the opinion to effectively end the right to abortion in the United States has cited himself more times than he cited female scholars combined.

Before anyone blows a gasket, allow me to list a few caveats: First, this was by no means a scientific endeavor. I am not going to submit this analysis for any awards. It has not been peer-reviewed. It was simply a good faith effort to read Alito’s draft closely and record every reference, both in the text and footnotes, made by name. In every case, I tried my best to identify each individual with a simple Google search.

Mind you, I counted every citation that mentions a scholar, regardless of why they were cited. Several of the female citations did little to support Alito’s argument for overturning Roe. In fact, of the five times he cites a female judge, three of those citations reference the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, an advocate for abortion rights. And in another case, Alito cites a female scholar only to characterize her work’s inclusion in Roe as “irrelevant.”

Here’s a section in which Alito lists some scholarly criticisms of Roe’s “reasoning.” He exclusively cites men:

All in all, Roe‘s reasoning was exceedingly weak, and academic commentators, including those who agreed with the decision as a matter of policy, were unsparing in their criticism. John Hart Ely famously wrote that Roe was “not constitutional law and g[ave] almost no sense of an obligation to try to be.” Ely 947. Archibald Cox, who served as Solicitor General under President Kennedy, commented that Roe “read[s] like a set of hospital rules and regulations” that “[n]either historian, layman, nor lawyer will be persuaded …. are part of… the Constitution.” Archibald Cox, The Role of the Supreme Court in American Government 113-114 (1976). Laurence Tribe wrote that “even if there is a need to divide pregnancy into several segments with lines that clearly identify the limits of governmental power, ‘interest-balancing of the form the Court pursues fails to justify any of the lines actually drawn.” Tribe 5. Mark Tushnet termed Roe a “totally unreasoned judicial opinion.” M. Tushnet, Red, White, and Blue: A Critical Analysis of Constitutional Law 54 (1988). See also [Philip] Bobbitt, Constitutional Fate 157 (1982); [Akhil Reed] Amar, Foreword: The Document and the Doctrine, 114 Harv. L. Rev. 26, 110 (2000).

The asymmetry in Alito’s draft is, to put it mildly, disappointing. But it also reflects who held—and often continues to hold—power in this country. After all, this is a document that may effectively govern the bodies of millions of uterus-owners. Shouldn’t we have more of a say in it?