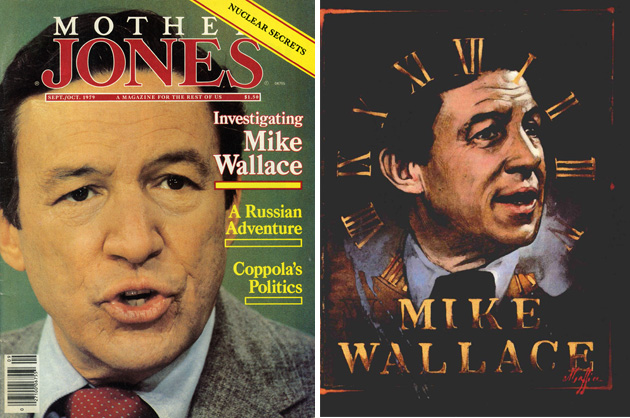

Cover of the September/October 1979 issue of Mother Jones; Illustration: Daniel Maffia

60 Minutes is by far the most popular public-affairs program in the history of American television. Recently there has been a flood of articles about the show—and about Mike Wallace in particular. Most have celebrated 60 Minutes‘ success, but have also wondered aloud whether Wallace and his colleagues aren’t becoming a little too aggressive. The US Supreme Court has also mused upon the show’s cheeky independence; this year it ruled that the plaintiff in a libel suit had the right to probe “the state of mind” of Wallace and his producer, in order to evaluate how fairly they made their editorial decisions.

Since television has become so many people’s daily newspaper, favorite entertainer, most reliable babysitter, and cheapest tranquilizer (not to mention its primary function as ingratiating salesman), it’s crucial that we question the tube’s influence. But it is the medium’s essential timidity—not its brash, tick-tick-tick, microphone-in-the-face reporting style—that demands scrutiny. Alas, the print journalists who report on television journalists are usually working for similar (if not the same) corporate employers. Fundamental questions that they should ask have been taboo for so long that there’s no need for censorship.

Because they are discouraged from probing into serious political and economic areas, many reporters are tempted to ask Mike Wallace when he stopped beating his wife. Since Wallace himself often browbeats and tricks his subjects into revealing themselves, he is fair game. But this overemphasis on technique leads off the main track: the medical quacks, diploma mills, bureaucratic boondoggles, vanity publishers, land frauds, religious humbugs, and corrupt county politicians whom 60 Minutes focuses upon should be exposed. We just wish that such an enterprising, prestigious program would investigate America’s major problems and spend less of its time on minor conmen.

Why 60 Minutes doesn’t go after the big fish—why it can’t—is the thrust of our interview. We wanted to find out how as curious, intelligent, and ambitious a journalist as Mike Wallace got channeled onto the bunco squad.

Wallace, however, wasn’t eager to be so questioned; he refused our initial request. When we persisted, he said repeatedly that he’d get back to us, and then never did. When later he begged off because of his grueling travel schedule, we offered to fly anywhere and interview him on the plane. This offer turned out to be doubly fruitful. We finally accompanied him from Los Angeles to New York City; during the course of the long, physically confining flight, Wallace relaxed and became remarkably candid.

Mother Jones: Why is such a large audience—roughly 35 million people each week—attracted to 60 Minutes?

Mike Wallace: I think we are perceived as ombudsmen—that more than any single other factor. No one really knows where Morley [Safer] or Dan [Rather] or Harry [Reasoner] or I stand on any particular issue. I think we’re perceived as fair, more daring and innovative than other broadcasts. Also, our pieces are constructed almost as morality plays.

MJ: Politically, how do you think you’re perceived by viewers?

MW: Maverick—or independent.

MJ: Is that true for all the correspondents?

MW: I’m sure that’s true for Morley and Harry. When Dan came aboard, the Republican people were unhappy that he’d joined the broadcast. That reaction took about six months to be blanched out.

MJ: So there’s an uneasiness when correspondents are perceived as having an ideology?

MW: I’m not sure about that. I was regarded by my peers at CBS News as the house conservative for a while, which I found rather funny because I’d come from a family of Roosevelt Democrats. And to begin with, my instincts were more liberal. But over a period of time I began to understand that the conventional wisdom was not necessarily wisdom; I covered Nixon, for example, in 1967-68 for CBS News. I found I came to him with fresh eyes because I’d never been exposed to him on a day-to-day basis. I was able to bring to my coverage of Nixon a less-than-doctrinaire view.

MJ: You also became friendly toward Agnew when he was running for governor of Maryland. How could you have so misjudged both these men?

MW: Well, let’s deal with Agnew first. If you go back to Agnew’s initial campaign, you’ll find many of the liberal Republicans and Democrats supported him. And at first, he was a not-illiberal governor. I got to know him early in his campaign, when he was going from house to house to address small gatherings. I rather liked the man, and he developed into a pretty good source. At conferences it’s fine for a journalist to have a relationship with a politician from whom one can get a quick reading of what’s going on behind the scenes. And I must say that Agnew—because I had been with him near the beginning—was pretty open. Little by little—after new reporters took cheap shots at him by reporting his “fat Jap” and “If you’ve seen one slum, you’ve seen them all” slips—Agnew believed himself beleaguered and captive of a hostile press. And then he acted out. After all, what was he? A county politician projected into national politics overnight.

MJ: This wasn’t the only time in your career that your contacts—being in close at the beginning—influenced your judgment. In 1968, after you covered his campaign, Nixon offered you a chance to be his press secretary. And you admitted that you were tempted to take the job, in order to see what life was like on the inside.

MW: If you talk to any of the four other reporters who were doing the preprimary coverage of Nixon, I think you will get the same story. He seemed to be a “new Nixon”—accessible to the press, reasonable. By his actions he conveyed the impression that he understood he would have to change the way he handled himself and his relationship to reporters. And the coverage that he got was first-rate—he almost served as his own press secretary at that time.

MJ: Nixon certainly must have made you and the others feel special, because even after you left for 60 Minutes, you kept up your admiration. In 1970, you said you were “not concerned that the administration is trying to play Big Brother.” Later you said you found Nixon admirable and attractive.

MW: Look, I came late to the game. Some of the things that Agnew said in his famed Des Moines speech—about the incestuous relations among the press, the silent majority, and the nattering nabobs of negativism—some of that I was inclined to agree with. So I found it difficult to acknowledge conspiracy theories about Nixon and Agnew. I thought that I knew these two men and their associates better than I did. I was simply wrong.

MJ: Let’s go on to 60 Minutes. In the past 10 years you’ve done a few exposés that involved big companies. And once you get such a story, you don’t seem afraid to run it. We were proud and impressed that you picked up our Ford Pinto exposé—Ford was and is one of your biggest sponsors. So this is not a question about guts, but why proportionally, do so few of the scandals you uncover deal with America’s largest corporations?

MW: It’s certainly not because of pressure from above. There has never been an instruction from anybody to that effect—up to and including stories about CBS. We took on CBS itself in our junkets and corporate perks pieces. In that corporate perks piece we also took on Dupont and Rockwell International. In the case of Valium, we took on Hoffmann-LaRoche.

MJ: But when you add up all the pieces 60 Minutes has done, these kinds of stories don’t constitute a big portion. And when you consider dollar amounts of business conducted in this country, the percentage is much, much lower. Is there some structural flaw in the way you conceive of stories? Are large corporations more difficult to catch?

MW: They are probably more difficult to catch. And then we have to bite off a 15- or 18-minute piece. Fraud inside a corporation, when it takes place—if it takes place—is not susceptible to that kind of treatment. I’m guessing now, because I’ve never really sat down to think of it; there’s never really been this kind of discussion, that I know of, at 60 Minutes. If you have a company president with his hand in the till, then you have a character on whom to focus. But other kinds of money pieces are sometimes quite hard to tell on television, because they’re complicated.

MJ: What’s an example of an important financial story that wouldn’t work on TV?

MW: Perhaps the Bert Lance investigation, because you’re talking about banks and loans; it’s a very technical story involving labyrinthine, if not Byzantine, financial dealings. It would be hard to tell that story without the full cooperation of all concerned.

MJ: The Lance investigation involves potential illegalities. What about an economic story that focused on questionable acts or trends that weren’t illegal? For example, the biggest corporations in this country are increasingly eating up other businesses. In 1978, the Fortune 500 bought up some 350 other companies, some of which were enormous themselves. Is that a kind of story 60 Minutes could do?

MW: Let’s say you were going to do stories on UV Industries. I happen to know—I play tennis with—a fellow by the name of Horowitz, who heads UV. Sharon Steel. Victor Posner. You absolutely need the participation and cooperation of these individuals to talk about the takeover, proxy fights. And that you do not get. And without the cast of characters, it’s a story you simply could not tell.

MJ: Could 60 Minutes do a story on structural unemployment, about unemployment that’s built into the system?

MW: It would be pretty hard.

MJ: Why?

MW: Well…I’m trying to think of how to go about it: Conceivably, if you had a fascinating couple of guys from management and labor, and you decided to do what is in effect an essay, a “talking heads” essay. But it is not a story that I’m immediately drawn to for 60 Minutes, I confess.

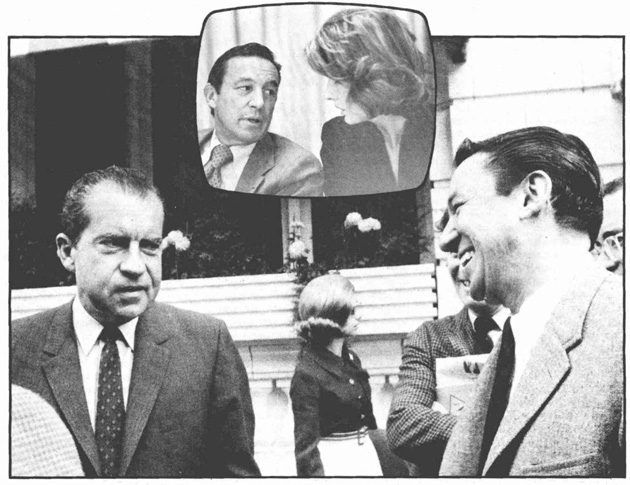

Wallace with Nixon during the 1968 campaign. Inset: With Nancy Kissinger at Bill Buckley roast.MJ: It seems that for a television story to work, you need not merely characters, but colorful ones. In a way television doesn’t care whether they’re radical or conservative. For example, a few years ago 60 Minutes did a good show on Robert Pollard right when he was quitting the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in protest over the inadequate monitoring of safety standards at a Consolidated Edison plant.

Wallace with Nixon during the 1968 campaign. Inset: With Nancy Kissinger at Bill Buckley roast.MJ: It seems that for a television story to work, you need not merely characters, but colorful ones. In a way television doesn’t care whether they’re radical or conservative. For example, a few years ago 60 Minutes did a good show on Robert Pollard right when he was quitting the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) in protest over the inadequate monitoring of safety standards at a Consolidated Edison plant.

MW: Now there’s a perfect example of a Fortune 500 corporation—Con Ed. And yet we took them on.

MJ: I bet you took a lot of flak for that story.

MW: We got a lot from Charles Luce, who wrote to Bill Paley [chairman of CBS], I understand.

MJ: Charles Luce?

MW: The head of Con Ed. He wrote to Paley to try to point out that we had done a less-than-faithful job. This, of course, was not true. That story today looks almost like a scenario for The China Syndrome.

MJ: Is that one of the stories you’re proudest of?

MW: We are certainly proud of that story. We took a lot of flak for it—[John J.] O’Connor, television critic of the New York Times, took us apart; he said the anti-nuclear bias of the piece was almost blatantly apparent.

MJ: That’s the only time I can think of that the Times criticized you on a substantive point. Why on this story?

MW: My estimation is that O’Connor was gotten to—and I don’t mean that in a pejorative sense—that he was reached by the NRC’s public relations counsel, who said that entrapment of Con Ed officials had taken place. That’s when other people began to write about our confrontation journalism, drama for drama’s sake.

MJ: Are those charges unfair?

MW: I think they’re fair comment, but basically invalid. They miss the point of how one gets a story. Had we come foursquare at the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and told them ahead of time just exactly what we knew and what we were after, we would have gotten a carefully rehearsed, PR answer to our questions.

MJ: The Times was a lot more helpful with your Johnny Carson piece. You framed that story—indeed you frame so many light and heavy pieces—around the discovery of just how much money an individual is making. Why?

MW: Well, I was amused that Johnny Carson, little by little—and I think for reasons of ego—let me find out that contrary to his published salary figure of $2.2 million or $3 or $3.7, that it was $5 million or more.

MJ: He let you find out?

MW: We had a little conversation, and, you know, some things are on film and some things are off. And then I confirmed the figure with his attorney, who shook his head, smiled, and said: “Ego. Ego.”

MJ: But why did finding out his salary make the piece important?

MW: It just seemed to me that it was quite an extraordinary sum. I thought it was a pertinent fact. NBC’s in trouble; their profits are down by half this year. And they are also in trouble with Carson, one of their biggest money generators.

MJ: Once you got that figure, plus the information that Carson was planning to leave The Tonight Show, how did you make these bits into news?

MW: Although hardly world-shaking in its implications, that’s a big entertainment story when the New York Times plays it on the front page.

MJ: But how did the Times get the information that he was thinking of leaving?

MW: They did a little reporting of what I was doing.

MJ: In other words, you leaked it to the Times. Otherwise, they would have no other way of knowing. You created a news item that made it into a big story.

MW: And waited 10 days before we put it on the air because I wanted to check my understanding with Carson and his attorney, since we had been planning just to run a profile in the fall.

MJ: Well, if Johnny Carson is news, how much of what you do is entertainment? In your boss Don Hewitt’s words, “People tune in 60 Minutes really to watch ‘The Adventures of Mike, Dan, Morley, and Harry.'” Do you agree?

MW: I’m not sure I would put it quite that way, but effectively, yes.

MJ: And to CBS executives, ultimately, you’re the same kind of star that Johnny Carson is.

MW: I’m sure they regard me as a valuable employee. But as far as compensation is concerned, it’s minuscule compared to entertainment broadcasts.

MJ: You make at least $250,000 a year just from 60 Minutes.

MW: I’ve never talked about specific figures that I make to anybody.

MJ: But you ask the question of everyone. And you wouldn’t say that a quarter-million annually was way off? [Wallace smiles while shaking his head no.]

MJ: Of course I’m going to report you shook your head no. And as a matter of fact, you admitted way back in 1957 that you were making $150,000 a year.

MW: So that if your current figure is right, I would be making less today—because of inflation—than I was making in 1957.

MJ: Unless you’ve made terrible investments, you must be a millionaire.

MW: If by that you mean: With the house that I own, and a bank account there, and a few stocks here, etc., etc., does it add up to a million? I would imagine, probably.

MJ: Now I know with sports stars, because of the leapfrogging of salaries it’s hard for them to feel well paid. Does any of you feel, “60 Minutes and I are as valuable to CBS as Carson is to NBC—I should be making more”?

MW: I think that those of us who were in at the borning of 60 Minutes and developed its character—it seems to me—are entitled to more compensation than we’re currently getting. After all, this year we were the top broadcast in circulation on all of CBS.

MJ: I understand that commercials on 60 Minutes now sell for as much as $215,000 a minute. Six years ago you were only getting about $25,000 a minute. It’s obvious that the executives are intent on maximizing profits.

MW: And particularly for this past year…In all fairness, CBS also regards its news division as the Tiffany of the Tiffany of the networks.

MJ: And the Tiffany reputation is also profitable.

MW: No doubt about it. I’m sure that the executives at CBS during these last two or three difficult years know full well that had it not been for the Cronkite news and 60 Minutes, there would have been many more defections of affiliate stations from CBS to ABC.

MJ: So does your own financial success affect your sympathies?

MW: You have to be the judge of that—take a look at the kinds of stories that I’ve done.

MJ: Let me ask the question another way: Why wouldn’t it affect your sympathies?

MW: Because I’m professional and have been at the job long enough to know that the day it begins to affect my judgment, I immediately diminish my own effectiveness.

MJ: But isn’t there an unconscious bias because your friends are wealthy and powerful?

MW: First of all, I’m not very close to very many people in high levels of industry or government. Occasionally I will see them at a dinner party or something of that sort…I don’t know why he said this, but recently Henry Kissinger commented to my wife, Lorraine, how pleased he was at the success of 60 Minutes and the kind of work that I’ve been doing on it. He also said: “And I particularly admire the fact that Mike has done it without compromise.” That’s all. Lorraine didn’t go on about it. But she was moved by the fact that he would say that.

MJ: Doesn’t William Shawcross’ book Sideshow, about Kissinger’s cynical bombing of Cambodia, affect your opinion of him?

MW: I read the Shawcross book with fascination, and I’m waiting for Henry’s book to see what side I come down on.

On Night Beat in 1957, where he made his reputation as an inquisitor. Inset: Wallace, who came out of showbiz, emcees with Ginger Rogers and Ronald Reagan.MJ: Tell me, why is income distribution never mentioned on 60 Minutes?

On Night Beat in 1957, where he made his reputation as an inquisitor. Inset: Wallace, who came out of showbiz, emcees with Ginger Rogers and Ronald Reagan.MJ: Tell me, why is income distribution never mentioned on 60 Minutes?

MW: How do you mean?

MJ: Well, women, for example, earn less than 65 percent of what men earn in this country for comparable jobs. And that’s for comparable jobs—most women are trapped in the pink-collar ghetto. You’ve never done a story on that.

MW: Well, the one story that I’ve done is about a head hunters firm—people who service various businesses, like CBS and Ralston Purina, to try to get women into jobs.

MJ: That’s one story about executives. Actually, your views on women’s liberation are notorious. Twenty-five years ago, you said: “It helps if a wife walks one step behind her husband. European women have that by-your-leave-my-lord attitude that you just don’t find in American women. They’re infinitely more self-absorbed. European women let the men run things and quite right they are too!” Good Housekeeping reminded you about this statement a couple of years ago, and you said: “I stand by every word.” Do you still?

MW: Not as firmly as I did then. I have a producer, Marion Goldin, who is the equal of anybody on my staff. And I value her very highly. Lorraine, before we got married, supported her children with her galleries and paintings. Liberated by no movement, liberated by herself. And in spite of that, Lorraine is essentially feminine.

MJ: A feminist can be feminine.

MW: So many feminists in our business lose that soft, round, appealing quality—I don’t know how else to define it.

MJ: Does this “attitude” enter your work? Since you don’t find feminists attractive, wouldn’t that discourage you from doing a story about them?

MW: On the contrary, if I regarded them as harpies, and harpies off on a wrong bent, and there were a story to tell about them, as far as I’m concerned that’s grist for the mill.

MJ: You’d certainly be less likely to profile women who weren’t particularly happy with the “femininity” they felt society had imposed on them.

MW: Again, you have to choose among the stories you can do each year, and, conceivably, I would not opt for that kind of piece.

MJ: All my questions about what you don’t cover lead toward a fundamental observation: You believe that there are individual instances of malfeasance in this society, but you don’t believe that there are structural flaws.

MW: How do I say this in a way that will not sound callous? There are flaws in our society, it’s quite apparent. But basically our society is one I have admiration for, one in which I am comfortable and one which I believe has served the vast majority of American people well. I am a Depression boy from Boston, with immigrant parents whose god was Franklin Roosevelt. I grew up to one-third of a nation ill-clothed, ill-housed, ill-fed. I don’t see that now. Maybe I’m, so to speak, “taking the train from Westchester into the middle of Manhattan,” and I don’t see the ghetto. Well, it’s not true, because I live 20 blocks from Harlem.

MJ: And you have a vacation home in Haiti.

MW: I have more than a vacation home there. We have a home and a shop, and it’s conceivable that we’ll retire there. But, by and large, I think America is proceeding fast enough to a planned economy. What that kind of economy has done to England over the past decade has—it seems to me—been a disaster. Sometimes England is almost a sad country to visit.

MJ: Don’t you think Haiti is a sadder country? It’s conceivably the poorest country in the world; it’s certainly the poorest in the Western Hemisphere.

MW: It may be, as far as dollar-income is concerned, one of the poorest. But Haiti is far from a sad country. Haiti under “Papa Doc” Duvalier was a terror-ridden country. But if you went to Port-au-Prince today, I promise that you would be stunned by the vitality, and the life, and the joy, and the dancing, and the music. And when you talk about income, there is so much hand-to-mouth living in the country that it never finds its way into the statistics.

MJ: By this comparison, and it shows up very clearly on 60 Minutes, one can tell you have a fairly low opinion of the efficacy of government intervention.

MW: Yes, I think that it too frequently bogs down in waste or malfeasance or boondoggling. I’m very cynical about it.

MJ: But you don’t have the same doubts about the efficacy of private corporate enterprise.

MW: I’m really not doctrinaire about that. I’ll come back to the Pinto and the lack of safety procedures and the willingness to put on television those professionally believable mavericks who will say that the emperor has no clothes.

MJ: But the main point we tried to make about the Pinto was that it was business as usual. Ford weighed how much the deaths would cost them versus how much it would cost to fix the car. And that cost-benefit analysis is central to every corporation in this country.

MW: It’s central to all kinds of reckoning. You will do the same thing in the way that you lead your life or raise your child. We’re constantly called upon to make those value judgments. I really don’t think that anybody sits down at the Ford Motor Company, or at Hoffmann-LaRoche, and says to himself: “Okay, there are going to be this many overdoses, or that many fiery deaths, and we are willing to buy them in order to keep the cost of the production down.” There are bound to be certain risks in mining uranium, producing nuclear power or manufacturing products that the consumer wants.

MJ: The issue is accountability. In a corporation, people are only accountable to make sure that profits go up every year. Let me put my question in sharper relief: A former colleague of yours at 60 Minutes told me: “Mike is a great reporter, but ultimately he’s a worm like all the rest of us. Invisible hand signals are passed from the top telling us what limits we cannot repeatedly cross over. That’s why 60 Minutes tends to be the Reader’s Digest of TV. If Bill Paley says to squirm, Mike—even though he’s a gold-plated worm—will squirm just like the rest of us.” This colleague of yours added: “And the first hand signal that’s passed is not to talk about these things. Mike, and anybody else who wants to remain with the network, will never admit that what I’m saying is true.” Is there the slightest truth to what this fellow says?

MW: Absolutely not.

MJ: Remember, we’re not talking about guts or censorship, but self-inhibition. You mean to tell me that you don’t identify with the upper-middle class and above so…

MW: Oh, conceivably, conceivably. One does stories that interest oneself.

MJ: CBS is about the 90th-biggest corporation in this country. If you consider net income, it’s about 65th. Its declared profits last year were $198 million. And that’s after all the high salaries. Could you do a story against the way that wealth is made in this country?

MW: “Against the way”? Why would we want to do a story “against” the way? Listen, I know that you’re saying: “Mike, no matter how good a job you do, you are a member of the establishment press. And the establishment press covers establishment stories in a fairly searching way, but you never question the basic premises of the society in which you live.” And I say back to you,”That probably is true.” By and large we are talking about the society that we live in as a given, but a given in which 60 Minutes has grown, survived and prospered, in spite of remarkable obstacles to our success. I’m not much of a social philosopher—I’m a reporter. You wish that I were more of a social analyst, more of a commentator. More of a social activist. But Saul Alinsky, I’m not.

MJ: I appreciate your being so frank with us. I just want to ask you a few final questions. Edward R. Murrow, who wasn’t nearly the interviewer or investigator that you are, nonetheless had a reputation as a courageous figure. No one doubts that Mike Wallace is extremely tough, but on what issues have you been courageous?

MW: I don’t know. That’s a good question. Frankly, it never occurred to me.

MJ: It never occurred to you to be courageous?

MW: I’ve never tried to be courageous. A maverick, maybe. But courageous—I don’t think so.

MJ: Looking back on the 35 or so years that you’ve been a journalist, isn’t there any issue about which you wish you had been?

MW: No. I like to think that I’ve been honorable and fair, and that I’ve let the chips fall wherever they were going to fall, no matter what my personal view has been. I carry little ideological baggage.

MJ: I’ve done some surveying of 60 Minutes‘ fans and it seems clear that liberals perceive you as a liberal and conservatives as a conservative.

MW: Nothing could please me more. I like to think of myself as drawing from both sides: Bill Buckley; Henry Kissinger; Abe Rosenthal, editor of the Times, except really he’s not all that liberal. I’m trying to think of a friend who’s a liberal…and I can’t come up with one right away. Shana, except she’s not really a personal friend…Ahhh, one of my regular Saturday morning tennis partners, I think basically he’s probably a communist.