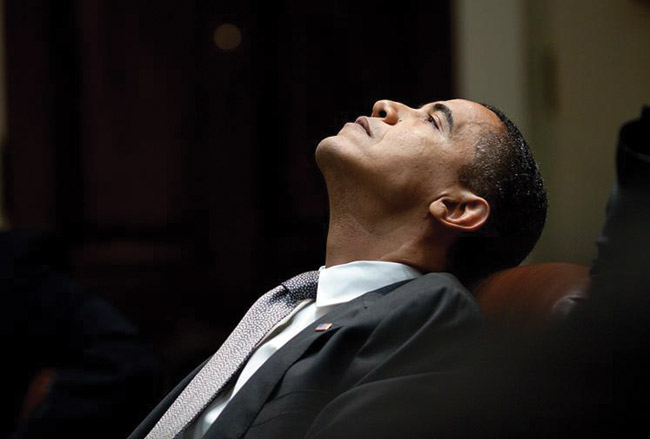

A number of big national banks stand accused of systematically bilking black and Latino borrowers. And the administration of our first black president is siding with the banks.

At the end of April, the Obama administration will go before the US Supreme Court to argue that those banks—including bailout recipients Bank of America, Citi, Wells Fargo, and JPMorgan Chase—should be allowed to duck a state investigation into their lending practices. If that sounds like the politics of the past, it is. The Obama administration has opted to maintain the stance of the Bush administration—one opposed by the NAACP and other major civil rights groups. And it won’t be some Bush holdover making the arguments in Cuomo v. The Clearing House Association (an industry group whose membership includes the world’s largest banks). Instead, the banks will be defended by the office of Obama’s new solicitor general, former Harvard Law School dean Elena Kagan, whom some conservatives have branded a “radical leftist” because of her record opposing military recruitment on college campuses.

The case got its start in 2005, when then-New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer discovered that many banks operating in his state were issuing a disproportionate number of high-interest loans to African Americans and Hispanics. Invoking state anti-discrimination laws, Spitzer wrote to those banks, politely asking for more information about their lending practices. He didn’t even issue a subpoena. Rather than respond to the request, the banks sued Spitzer. They argued that they were legally entitled to blow him off because federal banking law preempted the state investigation—that is, only the feds could make such a request, not some lowly state AG.

To make their case, the banks sought help from the Bush administration, through the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. The OCC is a little-known federal bank regulator that over the past decade has become increasingly active in helping those banks and their subsidiaries squash state efforts to rein in abusive predatory lending practices. The OCC joined the banks in the case as a plaintiff, asserting that a Civil War-era banking law made the OCC the only sheriff in town. When it came to big national banks like Bank of America and Wells Fargo, only the OCC, it argued, could force the banks to comply with state consumer protection laws like those banning racial discrimination in lending.

With the OCC’s backing, the banks prevailed in the trial court and the US Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit. New York’s current attorney general, Andrew Cuomo, has appealed the case to the Supreme Court, which will hear oral arguments in late April. Kagan’s office will be representing the OCC. The administration’s position in Clearing House stands in sharp relief to other parts of the US government, where financial system regulators have recently come out in opposition to shielding banks from state consumer protection laws and enforcement.

In March, on the same day Kagan was confirmed as solicitor general, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation chair Sheila Bair, a Bush appointee, told the Senate banking committee that “it is time to examine curtailing federal preemption of state consumer protection laws…it has now become clear that abrogating sound state laws, particularly regarding consumer protection, created an opportunity for regulatory arbitrage that frankly resulted in a race-to-the-bottom mentality.”

Yet in their briefs in Clearing House, lawyers for the OCC and Obama’s solicitor general say that the OCC has used its authority appropriately and has done a terrific job of protecting consumers from abusive bank practices. It’s a dubious claim at best. Until 2008, the OCC had never taken a public consumer protection action against a major bank. In fact, the OCC’s light touch with national banks prompted many state-chartered banks to switch their charters just so they could evade stricter state regulation.

In an amicus brief in Clearing House, lawyers for consumer advocates cite the example of Capital One, a company whose deceptive and unfair credit card practices were investigated for several years by the West Virginia attorney general. Three years into the investigation, the bank changed its status from a state-charted bank to an OCC-chartered bank. Less than two weeks later, Capital One asked a federal court to halt the attorney general’s investigation, arguing that the OCC was now the only entity that could initiate such a probe. The judge who heard the suit recognized that the bank was simply trying to evade the attorney general. Nonetheless, he believed the law required him to stop the state investigation.

Over the years, the OCC has tried to prevent state consumer protection actions against all sorts of shady practices. For instance, the OCC has intervened to prevent states from cracking down on telemarketing fraud and misbehavior by car dealerships, an unlicensed trade school, an air-conditioning company, and a mall that issued gift cards—all because each of these entities had a financing relationship with OCC-chartered banks. The OCC’s track record in enforcing anti-discrimination laws like those at the heart of the Clearing House case is equally dismal. In their amicus brief, consumer lawyers note that the OCC has brought only four formal enforcement actions under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act since 1987. And during the Bush administration, it didn’t refer a single discriminatory mortgage lending case to the Justice Department. Yet in her brief, Kagan argues that the OCC “vigorously enforces fair lending laws against national banks.”

Kagan’s brief appears as if it were largely written during the last administration, which it no doubt was. It touts the supposedly great work done by the OCC’s Customer Assistance Group, which Kagan and the OCC say has facilitated the recovery of tens of millions of dollars by injured consumers. Back in 2005, I filed a Freedom of Information Act Request with the OCC for information about how many people in this group actually investigated and resolved consumer complaints. The answer I eventually got many, many months later? Three, in an agency that fields more than 70,000 complaints a year from bank customers. In years past, the group has recouped less than $8 million annually for consumers—a drop in the bucket compared to the billions banks collect via abusive credit card practices or overdraft fees.

By comparison, the state attorneys general the OCC has tried to neutralize have successfully gone after many lending institutions for sleazy practices and recouped sums that dwarf anything the OCC has recovered. During the past decade, attorneys general in various states banded together and settled cases against Household and Ameriquest Mortgage Company, once some of the nation’s biggest subprime lenders. The AGs recouped more than $800 million for consumers, but they were often prevented from bringing similar cases against big banks because of OCC interventions. And in Clearing House, the Obama administration is now defending the OCC’s turf-conscious obstructionism.

The administration’s brief in Clearing House was due only six days after Kagan was confirmed. Reversing course in a case this far along would have been both legally and administratively problematic for her and the administration. But consumer advocates have seen a few hints between the lines of her brief that the administration intends to change its regulatory policy at the OCC. It is hard to imagine that Obama would really want to usurp the states and remake the OCC as the nation’s preeminent financial consumer protection agency. That would make the federal banking regulator ultimately responsible for policing thousands of unscrupulous car dealers, air-conditioning installers, trade schools, or even mall gift-card programs, simply because they had financing relationships with national banks. Not only does the OCC not have the resources to do all that; it has enough on its plate right now just keeping the banks afloat. As Daniel Mosteller, litigation counsel to the Center for Responsible Lending, observes, “Is the OCC really going to start investigating malls?”