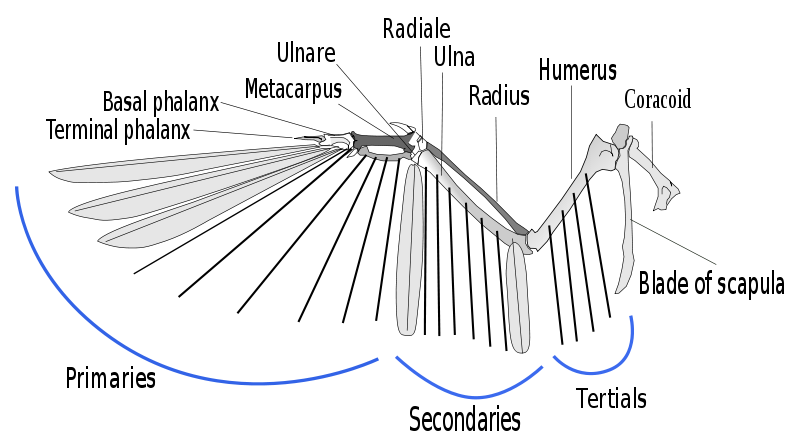

Illustration by L. Shyamal, Wikimedia Commons

A new study shows how North American birds have changed the shape of their wings in the past century as the landscapes around them have been fragmented by clear-cutting.

The research by André Desrochers from Université Laval involved the examination of 800 birds from museum collections. From his paper in Ecology:

Major landscape changes caused by humans may create strong selection pressures and induce rapid evolution in natural populations. In the last 100 years, eastern North America has experienced extensive clear-cutting in boreal areas, while afforestation has occurred in most temperate areas. Based on museum specimens, I show that wings of several boreal forest songbirds and temperate songbirds of non-forest habitats have become more pointed over the last 100 years. In contrast, wings of most temperate forest and early-successional boreal forests species have become less pointed over the same period. In contrast to wing shape, the bill length of most species did not change significantly through time.

Desrochers points out that these results are consistent with the habitat isolation hypothesis: that songbirds evolve changes in their mobility in response to changes in the amount and size of available habitat. Boreal forests have suffered severe deforestation over the past century. Thus, Desrochers predicted, songbirds from those areas would develop more pointed wings to enhance their flying abilities over the longer distances between habitat patches. Pointed wings are more energy efficient for sustained flight.

Another example of the complexity of landscape changes and their knock-on effects is given by Paul Ehrlich, David Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye in one of their excellent online ornithology essays on the Stanford U website. Here they describe the huge range expansion of cowbirds, a species that practices nest parasitism:

When Christopher Columbus landed, cowbirds are thought to have been largely confined to open country west of the Mississippi, because the continuous forests of the eastern United States did not provide suitable habitat for their ground feeding or social displays. As the forests were cleared, cowbirds extended their range, occupying most of the East but remaining rare until this century. Then increased winter food supply, especially the rising abundance of waste grain in southern rice fields, created a cowbird population explosion. The forest-dwelling tropical migrants—especially vireos, warblers, tanagers, thrushes, and flycatchers—have proven very vulnerable to cowbird parasitism. And that vulnerability is highest for those birds nesting near the edge of wooded habitat and thus closest to the open country preferred by the cowbirds.

Desrochers points out that the rapid physical evolution seen in the birds in his analysis could mitigate—though not necessarily prevent—regional extinctions.

Thanks to Rob Goldstein for his excellent blogging at Conservation Maven for the heads-up on the Ecology paper.