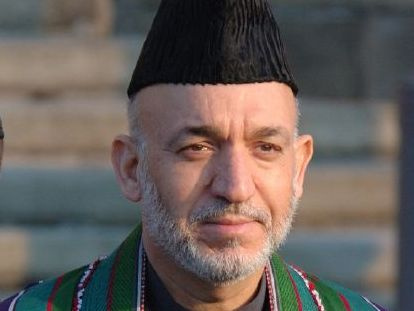

What’s up with Hamid Karzai? That’s the question on the minds of Afghan watchers in and outside of government following the resignations of two top officials who were respectively responsible for the country’s intelligence service and internal security apparatus. As I describe in my piece on this topic today, they weren’t just any bureaucrats. They were widely viewed as two of the most solid administrators in the Afghan government. Highly trusted, they had developed a strong rapport with US and NATO officials who are now understandably alarmed by their departures.

Officially, the cause for the resignations of Interior Minister Hanif Atmar and intelligence chief Amrullah Saleh was the failure of their agencies, and the collective security forces and operatives under their command, to prevent an attack targeting Karzai’s highly publicized peace jirga. Beyond two of the militants involved in the assault, who were killed by Afghan forces, there were no other casualties. As Karzai’s office has portrayed it, removing Atmar and Saleh was a matter of accountability (“Someone had to take responsibility for this,” Karzai’s spokesman, Waheed Omar, said.) But in a government where corruption and cronyism are rampant, you’d think Karzai could think of better people to make examples of. Karzai’s office insists that that attack was the sole reason why Atmar and Saleh resigned. But there were other issues at play. Among other things, both officials reportedly had disagreements with Karzai over his strategy for political reconciliation with the Taliban.

In today’s New York Times, Alissa Rubin has an interesting (and troubling) look at the psychology behind Karzai’s latest move—a move that certainly seems to run contrary to his goal of forging a strong central government:

To some, the forced departure of the two men is a troubling indication of the president’s mounting insecurity and his fear that even those closest to him are not looking out for him.

Compounding those fears is Mr. Karzai’s lack of faith in the Americans and his uncertainty about whether they will back him over the long term. That impression has been reinforced by President Obama’s pledge to start withdrawing troops in July 2011 and his administration’s arm’s-length relationship with President Karzai.

“The root of this is the perception that President Karzai got last year from the kind of cold reception that he got from the American administration, and that made him feel insecure,” said Ahmed Ali Jalali, who was Afghanistan’s interior minister from 2003 to 2005. He now teaches at the National Defense University in Washington.

The insecurity has left Mr. Karzai alternately lashing out in anger and searching for new allies, turning to Iran and elements within the Taliban. Both are antagonistic to American interests.

“He is trying to create new networks, new allies and contacts both inside the country and outside the country in case there’s a premature withdrawal, so a lot of this is more of a survival gesture,” Mr. Jalali said.

The bottom line, according Rubin’s piece, is that Karzai’s survival instinct has taken over. One question is how far he’s willing to go to ensure his own political survival. Another is the degree to which the Obama administration’s initial tough love approach to the Afghan president may have compounded an already difficult situation.