Mac McClelland

It’s hard to believe BP lets visitors onto its relief-well rig: The guys onboard say that once, a Coast Guard guest took his safety glove off to swipe his hand through some toxic drilling mud; another time, a member of the media, when given access to the control bridge, randomly pressed a button and asked, “What’s this do?”

It’s even harder to believe BP would let me onto its rig, what with the months I’ve spent trying to get around the company’s media blockade and hounding its flacks for access and information. But last weekend the company offered me a rare spot on a flight into the Gulf of Mexico on an S-92A Sikorsky helicopter. Our destination was the Development Driller II—or DDII, as the cool kids call it—one of the two rigs drilling relief wells near the now-capped Deepwater Horizon site. In addition to BP and Transocean reps, there were three other reporters (Times of London, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, a TV anchor from Alabama) on board. We all carried emergency medical forms granting authorization for blood transfusions, ready to be pulled from our pockets in the event that something horrible happened to us.

The DDIII, just visible across the choppy waves, is the other rig. It’s poised to perform a “bottom kill” procedure as soon as the Coast Guard and BP give it the go-ahead, when pressure testing is complete. The DDII is its backup. (It was sent over from another of BP’s Gulf projects, the Atlantis field, home to 16 producing wells and a platform that a lot of people are concerned is not safe to operate.)

The DDIII, just visible across the choppy waves, is the other rig. It’s poised to perform a “bottom kill” procedure as soon as the Coast Guard and BP give it the go-ahead, when pressure testing is complete. The DDII is its backup. (It was sent over from another of BP’s Gulf projects, the Atlantis field, home to 16 producing wells and a platform that a lot of people are concerned is not safe to operate.)

Each rig costs $1 million a day to operate. Assuming everything goes well on the DDIII, the DDII will help permanently shut down the well. But for now, wellsite leader Mickey Frugé says, the word is “Hurry up and wait.”

As such, it’s pretty quiet aboard the DDII. Frugé said some of the crew was doing maintenance. Many of them, one of the guys told us, were hiding because we were there, and I’m not sure how much he was kidding. Wherever they were, they were no doubt engaged in wholesome fun: Per company regulations, no booze, no drugs, and no porn are allowed on the rig. Frugé listed Wii, foosball, Internet surfing, watching movies, and “walking around the helipad” as popular shipboard activities.

Everything on the guided tour seemed swell. We met many charming and confident personnel. We were told we had to keep our hard hats securely fastened to our shirt collars by a strap, lest the wind knock them off our heads; even so much as a styrofoam cup that gets dropped into the ocean, we were reminded several times, has to be reported to BP’s environmental department. We were shown the lifeboats, two of them, which seat 88 people each, enough to fit exactly every single person onboard.

We met two guys in the Main Drill Cabin, or drill shack, a glass-fronted cage overlooking the hole where drill bits are lowered, or mud is pumped—or where an explosion would originate if something went wrong. Like plenty of the workers, the one of the two young guys manning the control chairs knew someone who’d died on the Deepwater Horizon. “Does it make you nervous that this is the worst place to be sitting if something blows up?” I asked his coworker.

“Well, the goal is not to let it blow up,” he said, shaking his head like I was being silly.

He rattled off about 19 safeguards and contingency plans for possible problem scenarios, gesturing beyond the roof of the drill shack, where equipment hung high overhead, waving his hand in the direction of the blowout preventer control panel, a colorful computerized touch-screen graphic on the wall. “Nah, I never worry about it. There’s nothing to worry about if you stay on top of your shit.”

What the guys did seem a little concerned about was how this whole scene was being taken in by the visiting press. Every chat I had with a rig worker included him asking me at some point, sort of nervously, “So what do you think?” One of the captains asked me what I was going to write about. I told him I didn’t have anything hard-hitting to say about the nice things I’d been shown. “So you’re not going to bury us?” he asked, because it probably sucks to work hard for an industry vilified by large portions of your country.

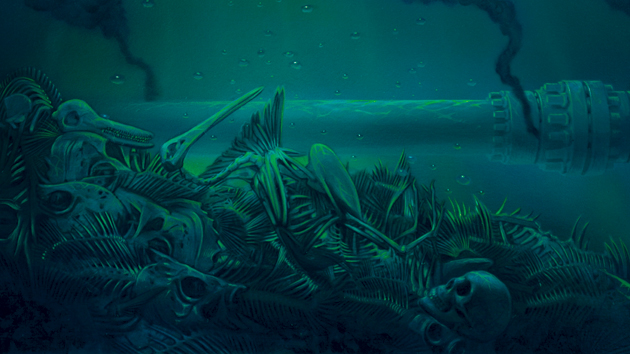

The ROV control room

The ROV control room

We asked several of the workers we encountered how they felt about the deepwater drilling moratorium. Are they worried about their jobs? Their futures? Not really, they said. There’s no reason to think the ban will be indefinitely extended. “I’ve been at this company for 20 years, and my family’s been in this company, and there’s no point in worrying,” Frugé told me before we left. “I’m not going to think about it unless it’s actually declared.”

And so, after a couple of pleasant and uneventful hours on the DDII, we said goodbye to the crew. Fortunately, the jokey warning Frugé had issued to us earlier had proved unnecessary. “If you see me runnin’,” he’d said, smiling, when we’d first arrived, “y’all better be runnin’ too.”

Special Report: Check out our in-depth investigation of BP’s crimes in the Gulf, “BP’s Deep Secrets.”