<a href="http://www.tompkinssquare.com/">Tompkins Square Records</a>.

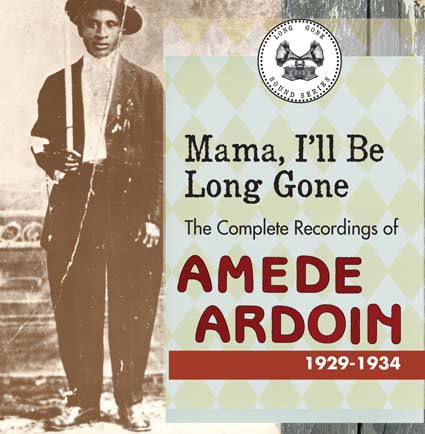

Amede Ardoin

Mama, I’ll Be Long Gone

Tompkins Square Records

While playing his accordion at a local farmhouse in Eunice, Louisiana, in the late 1930s, Creole musician Amede Ardoin wiped his brow with a handkerchief given to him by a white woman. Two white men angered by the exchange between Ardoin and the woman followed him outside, where they beat him, backed over him with a Ford Model A truck and threw him in a ditch. He woke up crippled, with permanent brain damage. Fellow musician Canray Fontenot remembers how that night changed his friend: After that, “he didn’t know whether he was hungry or not…. He was plumb crazy.”

That’s the point when Amede Ardoin, known today as the father of Cajun and Zydeco music, seemed to vanish. His friends—at least the ones who would later help compile the scant record we have of Ardoin’s life—appeared to lose track of him. In fact, the only official traces of Amede Ardoin are his draft registration card, his name on a Census count, one washed-out photograph, and 34 recordings he made between 1929 and 1934, rereleased this month in one collection for the first time.

Mama, I’ll Be Long Gone contains all known recordings Ardoin made during four sessions in New Orleans, San Antonio, and New York City. With songs like “Two Step de Eunice” and “Blues De Basille,” Ardoin, helped by his fiddle player and traveling companion Denis McGee, became one of the first—if not the first—musicians to record Louisiana’s Cajun music. Ardoin was an accordian virtuoso who, by all accounts, had an uncanny knack for improvising French lyrics with his strange high voice.

It might seems strange that a black Creole musician who left little more of a trace on the world than 34 scratchy recordings would come to be known as the father of a musical style rooted in the culture of French-Canadian exiles. In this sense, the record stands as a testament to the musical creativity happening in Louisiana during the first half of the 20th Century. Around the same time Ardion was mastering his accordion, musicians like Jelly Roll Morton and Buddy Bolden were in nearby Storyville, New Orleans, shaping ragtime music into jazz.

It’s unlikely we’ll ever know for certain what became of Ardoin. By some accounts, he wound up in a mental institution in Pineville, Louisiana. The only concrete evidence of this, however, is a death certificate issued May 30, 1941 from Pineville for a person named “Amelie Ardoin.” And the certificate lists Ardoin as being 20 years older than he actually was at the time. Others say Ardoin eventually left Pineville and headed home. If so, he may well have been singing “La Valse Ah Abe” as he wandered down the road with his accordian: “I’m going home alone, to live the life of an orphan…“

Click here for more Music Monday features from Mother Jones.

Front page image: Public Domain/Wikimedia