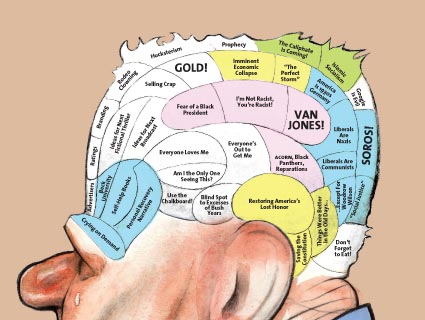

Illustration: Steve Brodner. Click here for a larger version of this illustration.

Illustration: Steve Brodner. Click here for a larger version of this illustration.

IT TAKES TWO THINGS to make a political lie work: a powerful person or institution willing to utter it, and another set of powerful institutions to amplify it. The former has always been with us: Kings, corporate executives, politicians, and ideologues from both sides of the aisle have been entirely willing to bend the truth when they felt it necessary or convenient. So why does it seem as if we’re living in a time of overwhelmingly brazen deception? What’s changed?

Today’s marquee fibs almost always evolve the same way: A tree falls in the forest—say, the claim that Saddam Hussein has “weapons of mass destruction,” or that Barack Obama has an infernal scheme to parade our nation’s senior citizens before death panels. But then a network of media enablers helps it to make a sound—until enough people believe the untruth to make the lie an operative part of our political discourse.

For the past 15 years, I’ve spent much of my time deeply researching three historic periods—the birth of the modern conservative movement around the Barry Goldwater campaign, the Nixon era, and the Reagan years—that together have shaped the modern political lie. Here’s how we got to where we are.

PROLOGUE

Just Making Stuff Up

WHEN AN EXPLOSION sunk the USS Maine off the coast of Havana on February 15, 1898, the New York Journal claimed two days later, “Maine Destroyed By Spanish: This Proved Absolutely By Discovery of the Torpedo Hole.” There was no torpedo hole. The Journal had already claimed that a Spanish armored cruiser, “capable, naval men say, of demolishing the great part of New York in less than two hours,” was on its way. “WAR! SURE!” a banner headline announced.

The instigator was a politically ambitious publisher, William Randolph Hearst. Kicked out of Harvard for partying, and eager to make a name for himself outside the shadow of his mining-magnate father, he made his way to New York, where he led the way in a sensationalist new style of newspaper publication—”yellow journalism.” In a fearsome rivalry with Joseph Pulitzer, he chose as his vehicle the sort of manly imperialism to which the Washington elites of the day were certainly sympathetic—although far too cautiously for Hearst’s taste. “You furnish the pictures,” he supposedly telegraphed a reporter, “and I’ll furnish the war.” The tail wagged the dog. At a time when the only way to communicate rapidly across long distances was via telegraph, it proved easy to make up physical facts.

More than six decades later, that still seemed to be the case. “Some of our boys are floating around in the water,” Lyndon Johnson told congressmen to goad them into passing the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution authorizing war in 1964, after a supposed attack on an American PT boat. “Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish,” LBJ observed later, after the deed was done. That resolution inaugurated a decade of official American military activities in Southeast Asia (unofficially, we had been carrying out secret acts of war for years). A full-scale air war began the following February, after the enemy shelled the barracks of 23,000 American “advisers” in a South Vietnamese town called Pleiku. But that was just a pretext. “Pleikus are like streetcars,” LBJ’s national security adviser, McGeorge Bundy, said—if you miss one, you can always just hop on another. The bombing targets had been in the can for months, even as LBJ was telling voters on the campaign trail, “We are not about to send American boys 9 or 10,000 miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves.”

It would have been possible all along for some intrepid soul to drop the dime on the whole thing. There were many who knew or suspected the truth, but with a villain as universally feared as communism was during the Cold War years, denying the facts felt like the only patriotic thing to do.

Then everything changed.

The ’70s

Question Authority

WALTER CRONKITE traveled to Saigon after the Tet Offensive in 1968, saw things with his own eyes, and told the truth: The Vietnam War was stuck in a disastrous stalemate, no matter what the government said. That was a watershed. By 1969, none other than former Marine Commandant David M. Shoup endorsed a book on the war called Truth Is the First Casualty. In 1971, Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers, the Department of Defense study that plainly revealed that just about everything Americans had been told about Southeast Asia was flat-out untrue. When the Nixon administration ordered the newspapers not to publish the Papers, Supreme Court Justice Hugo* Black thundered back that “for the first time in the 182 years since the founding of the Republic, the federal courts are asked to hold that the First Amendment does not mean what it says.” The searing melodrama of the Watergate investigation exposed new Nixon lies every day.

America, it seemed, had had enough. In the mid-’70s, the investigating committees of Sen. Frank Church and Rep. Otis Pike revealed to a riveted public that the CIA had secretly assassinated foreign leaders and the FBI had spied on citizens. Ralph Nader became a celebrity by exposing corporate lies. The mood of the Cold War had been steeped in American exceptionalism: The things America did were noble because they were done by America. Now, it appeared that America just might be susceptible to the same cruel compromises and corruptions as every other empire the world has known. Truth-telling became patriotic—and the more highly placed the liar, the more heroic the whistleblower.

The investigative reporter became a sexy new kind of hero—a shaggy-haired loner, too inquisitive for his own good, played by Warren Beatty and Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman. Jimmy Carter, the peanut farmer from Plains, swooped in from nowhere to take the White House on the strength of the modest slogan “I’ll never lie to you.” And during his presidency, one of the grand, founding lies of western civilization itself—that there need be no limits to humans’ domination of the Earth—was questioned as never before.

The truth hurt, but the incredible thing was that the citizenry seemed willing to bear the pain. All sorts of American institutions—Congress, municipal governments, even the intelligence community (the daring honesty of CIA Director William Colby about past agency sins was what helped fuel the Church and Pike investigations)—launched searching reconstructions of their normal ways of doing business. Alongside all the disco, the kidnapped heiresses, and the macramé, another keynote of 1970s culture was something quite more mature: a willingness to acknowledge that America might no longer be invincible, and that any realistic assessment of how we could prosper and thrive in the future had to reckon with that hard-won lesson.

Then along came Reagan.

* Correction: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this article included the wrong first name for Justice Black.

The ’80s

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

IN RESEARCHING this period, I’ve been surprised to discover the extent to which Ronald Reagan explicitly built his appeal around the notion that it was time to stop challenging the powerful. A new sort of lie took over: that the villains were not those deceiving the nation, but those exposing the deceit—those, as Reagan put it in his 1980 acceptance speech, who “say that the United States has had its day in the sun, that our nation has passed its zenith.” They were just so, so negative. According to the argument Reagan consistently made, Watergate revealed nothing essential about American politicians and institutions—the conspirators “were not criminals at heart.” In 1975, upon the humiliating fall of Saigon, he paraphrased Pope Pius XII to make the point that Vietnam had in fact been a noble cause: “America has a genius for great and unselfish deeds. Into the hands of America, God has placed the destiny of an afflicted mankind.”

The Gipper’s inauguration ushered in the “Don’t Worry, Be Happy” era of political lying. But it took a deeper trend to accelerate the cultural shift away from truth-telling-as-patriotism to a full-scale epistemological implosion.

Reagan rode into office accompanied by a generation of conservative professional janissaries convinced they were defending civilization against the forces of barbarism. And like many revolutionaries, they possessed an instrumental relationship to the truth: Lies could be necessary and proper, so long as they served the right side of history.

This virulent strain of political utilitarianism was already well apparent by the time the Plumbers were breaking into the Democratic National Committee: “Although I was aware they were illegal,” White House staffer Jeb Stuart Magruder told the Watergate investigating committee, “we had become somewhat inured to using some activities that would help us in accomplishing what we thought was a legitimate cause.”

Even conservatives who were not allied with the White House had learned to think like Watergate conspirators. To them, the takeaway from the scandal was that Nixon had been willing to bend the rules for the cause. The New Right pioneer M. Stanton Evans once told me, “I didn’t like Nixon until Watergate.”

Though many in the New Right proclaimed their contempt for Richard Nixon, a number of its key operatives and spokesmen in fact came directly from the Watergate milieu. Two minor Watergate figures, bagman Kenneth Rietz (who ran Fred Thompson’s 2008 presidential campaign) and saboteur Roger Stone (last seen promoting a gubernatorial bid by the woman who claimed to have been Eliot Spitzer’s madam) were rehabilitated into politics through staff positions in Ronald Reagan’s 1976 presidential campaign. G. Gordon Liddy became a right-wing radio superstar.

“We ought to see clearly that the end does justify the means,” wrote evangelist C. Peter Wagner in 1981. “If the method I am using accomplishes the goal I am aiming at, it is for that reason a good method.” Jerry Falwell once said his goal was to destroy the public schools. In 1998, confronted with the quote, he denied making it by claiming he’d had nothing to do with the book in which it appeared. The author of the book was Jerry Falwell.

Direct-mail guru Richard Viguerie made a fortune bombarding grassroots activists with letters shrieking things like “Babies are being harvested and sold on the black market by Planned Parenthood.” As Richard Nixon told his chief of staff on Easter Sunday, 1973, “Remember, you’re doing the right thing. That’s what I used to think when I killed some innocent children in Hanoi.”

1990-Present

False Equivalencies

CONSERVATIVES hardly have a monopoly on dissembling, of course—consider “I did not have sexual relations with that woman.” Progressives’ response has always been that right-wing mendacity—cover-ups of constitutional violations like Iran-Contra; institutionalized truth-corroding tactics like when the Republican National Committee circulates fliers claiming that Democrats seek to outlaw the Bible—is more systematic. But the deeper problem is a fundamental redefinition of the morality involved: Rather than being celebrated, calling out a lie is now classified as “uncivil.” How did that happen?

Back in the days when network news was the only game in town, grave-faced, gravelly voiced commentators like David Brinkley and Eric Sevareid—and on extraordinary occasions anchors like Walter Cronkite—told people what to think about the passing events of the day. Much of the time, these privileged men unquestioningly passed on the government’s distortions. At their best, however, they used their moral authority to call out lies with a kind of Old Testament authority—think Cronkite reporting from Saigon. It drove Johnson out of office, and it drove the right berserk.

On November 3, 1969, Richard Nixon gave a speech claiming he had a plan to wind down the war. The commentators went on the air immediately afterward and told the truth as they saw it: that he had said nothing new. Ten days later, the White House announced that Vice President Spiro Agnew was about to give a speech that it expected all three networks to cover—live.

The speech was an excoriation of those very networks and their Stern White Men—”this little group of men who not only enjoy a right of instant rebuttal to every presidential address, but more importantly, wield a free hand in selecting, presenting, and interpreting the great issues of our nation…. The American people would rightly not tolerate this kind of concentration of power in government. Is it not fair and relevant to question its concentration in the hands of a tiny and closed fraternity of privileged men, elected by no one, and enjoying a monopoly sanctioned and licensed by government?” Those in the habit of exposing the sins of the powerful were no longer independent arbiters—they were liberals. Such was the bias, Agnew argued, of “commentators and producers [who] live and work in the geographical and intellectual confines of Washington, DC, or New York City,” who “bask in their own provincialism, their own parochialism.”

Foreshadowing Reagan’s framing of reform-minded truth-telling as a brand of elitist meddling, Agnew singled out for opprobrium the kind of reporting that “made ‘hunger’ and ‘black lung’ disease national issues overnight” (quotation marks his). TV reporting from Vietnam had done “what no other medium could have done in terms of dramatizing the horrors of war”—and that, too, was evidence of liberal bias.

Agnew’s remarks reinforced a mood that had been building since at least the 1968 Democratic National Convention, when many viewers complained about the media images of police beating protesters. By the 1980s the trend was fully apparent: News became fluffier, hosts became airier—less assured of their own moral authority. (Around this same time, TV news lost its exceptional status within the networks—once accepted as a “loss leader” intended to burnish their prestige, it was increasingly subject to bottom-line pressures.)

There evolved a new media definition of civility that privileged “balance” over truth-telling—even when one side was lying. It’s a real and profound change—one stunningly obvious when you review a 1973 PBS news panel hosted by Bill Moyers and featuring National Review editor George Will, both excoriating the administration’s “Watergate morality.” Such a panel today on, say, global warming would not be complete without a complement of conservatives, one of them probably George Will, lambasting the “liberal” contention that scientific facts are facts—and anyone daring to call them out for lying would be instantly censured. It’s happened to me more than once—on public radio, no less.

In the same vein, when the Obama administration accused Fox News of not being a legitimate news source, the DC journalism elite rushed to admonish the White House. Granted, they were partly defending Major Garrett, the network’s since-departed White House correspondent and a solid journalist—but in the process, few acknowledged that under Roger Ailes, another Nixon veteran, management has enforced an ideological line top to bottom.

The protective bubble of the “civility” mandate also seems to extend to the propagandists whose absurdly doctored stories and videos continue to fool the mainstream media. From blogger Pamela Geller, originator of the “Ground Zero mosque” falsehood, to Andrew Breitbart’s video attack on Shirley Sherrod—who lost her job after her anti-discrimination speech was deceptively edited to make her sound like a racist—to James O’Keefe’s fraudulent sting against National Public Radio, right-wing ideologues “lie without consequence,” as a desperate Vincent Foster put it in his suicide note nearly two decades ago. But they only succeed because they are amplified by “balanced” outlets that frame each smear as just another he-said-she-said “controversy.”

And here, in the end, is the difference between the untruths told by William Randolph Hearst and Lyndon Baines Johnson, and the ones inundating us now: Today, it’s not just the most powerful men who can lie and get away with it. It’s just about anyone—a congressional back-bencher, an ideology-driven hack, a guy with a video camera—who can inject deception into the news cycle and the political discourse on a grand scale.

Sure, there will always be liars in positions of influence—that’s stipulated, as the lawyers say. And the media, God knows, have never been ideal watchdogs—the battleships that crossed the seas to avenge the sinking of the Maine attest to that. What’s new is the way the liars and their enablers now work hand in glove. That I call a mendocracy, and it is the regime that governs us now.