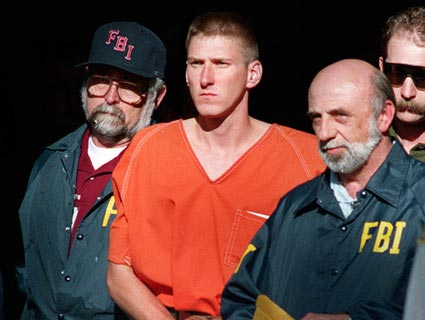

Timothy McVeigh is escorted from the courthouse in Perry, Oklahoma. Bob Owen/Zuma

In 2007, Mother Jones was the first national media outlet to tell the full story of Jesse Trentadue and his quest for the truth, which began four months after the attack on Oklahoma City’s Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building on April 19, 1995, killed 168 people. It was then that Trentadue, a Salt Lake City lawyer, learned that his brother, a construction worker and one-time bank robber, had died in a federal prison in Oklahoma City.

Prison officials said the prisoner had hanged himself. But Kenney Trentadue, who had never revealed any suicidal inclination, was shipped home for burial with bruises all over his body and lacerations on his face and throat—suggesting something more sinister. Even Oklahoma City’s chief medical examiner would later say, publicly, that it was “very likely he was murdered.” But the most compelling evidence in the case was altered or turned up missing. Jesse Trentadue was never able to prove what had actually happened to his brother—though he did win a $1.1 million civil suit for “emotional distress” to his family, based on the way the government had handled the aftermath of Kenney’s death.

Trentadue had all but given up, when, in the spring of 2003, he got a call from a small-town newspaper reporter in Oklahoma named J.D. Cash. Cash told him that Kenney very much resembled the police sketch of John Doe No. 2, whom the FBI initially believed to be a second bomber in the Oklahoma City attack. Cash also pointed out that both Kenney and John Doe No. 2 resembled Richard Lee Guthrie, a notorious figure on the racist far right. In 1994 and 1995, Guthrie and his gang, which called itself the Aryan Republican Army (ARA), had carried out 22 bank robberies across the Midwest, netting some $250,000 to support their white-supremacist movement.

Might federal officials have believed that Kenney Trentadue was in fact Richard Lee Guthrie, and that Guthrie was John Doe No. 2? Could he have been beaten to death in an interrogation gone bad? That theory provided what Jesse believed might be a missing motive for his brother’s murder, and he set about learning all he could about the federal investigations of the bombing and the Aryan Republican Army.

By 2003, however, the Oklahoma City case was closed. Timothy McVeigh was declared the lone bomber and executed for his crime; Terry Nichols, named as his sole accomplice, was serving a life sentence in a federal supermax in Florence, Colorado. Federal officials denied—and the judge in the McVeigh trial rebuffed—any attempts to show that McVeigh and Nichols hadn’t acted alone. Stonewalled at every turn, Trentadue remained determined to satisfy his curiosity. His primary tool would be the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

An initial batch of documents, received through a FOIA request, showed that the FBI was investigating a link between the bombers and Guthrie’s ARA. The connection involved a remote religious compound called Elohim City in eastern Oklahoma’s Ozark Mountains, a kind of sanctuary for far-right extremists from the Klan and the Aryan Nations to the then-burgeoning militia movement that inspired McVeigh.

The documents revealed that federal law enforcement had informants close to Elohim City. As I wrote in my original story, they also showed

…that the bureau was interested in any communication between McVeigh and the ARA immediately before the bombing, and that Guthrie himself was in Pittsburg, Kansas—some 200 miles from Oklahoma City—three days before the attack. In addition, the memos indicate that the FBI received reports of McVeigh calling and possibly visiting Elohim City before the bombing, at one point seeking “to recruit a second conspirator.”

The documents also have one source reporting that McVeigh had a “lengthy relationship” with someone at Elohim City, and that he called that person just two days before the bombing. (These documents were never shown to McVeigh’s lawyer.) The Justice Department and the FBI would not comment on the documents; an FBI spokesman in Oklahoma City told me that the bureau is confident it has caught and convicted those responsible for the bombing.

After the story ran, Trentadue continued his quest for information. He tried to depose Terry Nichols, along with a federal inmate named David Paul Hammer, who said he had talked with McVeigh at length while they were on death row together. A federal district court judge in Utah gave Trentadue the go-ahead, but his decision was reversed by the 10th US Circuit Court of Appeals. Trentadue also learned from the CIA that it had a spy satellite over Oklahoma at the time of the bombing, but the agency withheld details from him due to national security concerns.

Trentadue placed one FOIA after another, always getting the runaround from the FBI. Finally, after three years, he persuaded Clark Waddoups, another Utah-based federal judge, to order the FBI to respond by June 30, 2011. Trentadue was particularly interested in 20 or more video surveillance tapes from cameras located on the Murrah building—cameras that might have shown, among other things, whether McVeigh was alone when he parked a truckload of explosives beneath the building and then fled from his truck.

Earlier, the FBI had produced a document suggesting that the videotapes didn’t exist, based on an investigatory report “in which an individual personally involved in clearing the Murrah building after the bombing with apparent familiarity with its surveillance systems, stated that it was ‘a shame…that the surveillance cameras were never hooked up again after they put in a new security system approximately two years ago.'” The person in question was an elevator repairman who had done some work in the Murrah building and had gone there shortly after the blast.

But Trentadue argued that the cameras were indeed operational at the time of the bombing, citing two affidavits he’d obtained. The first one came from Don Browning, an Oklahoma City police officer (now retired) who shortly after the blast had “observed men wearing jackets with ‘FBI’ printed on the back removing the surveillance video cameras from the exterior of the Murrah Federal Building. I thought this was part of the FBI’s evidence gathering or ‘chain of custody’ procedures since those exterior cameras would have shown and recorded delivery of the bomb in a Ryder truck that morning as well as the person or persons who exited that truck.”

The second affidavit came from Joe Bradford Cooley, an employee for a subcontractor bidding on running the surveillance system. Cooley said he made frequent inspections of the system, including cameras and monitors, and that everything was running correctly up to the time the bomb went off. In addition, a Secret Service timeline of that day refers to one observer who said, “Security video shows Ryder truck pulling up to the federal building and then pausing (7 to 10 seconds) before resuming into a slot in front of the building.”

Now, in a sworn declaration to the court, David M. Hardy, a section chief in the FBI’s Records Management Division, said that he was “unaware of the existence or likely location of additional tapes…and do not know of anyone who would know where additional tapes would be located.”

The judge ordered the FBI to search its records manually, but the bureau resisted, arguing that the courts had previously relieved it of doing manual searches, and that “a manual search of the first 14 day worth of records in the OKBOMB case file would be extremely burdensome…Hardy estimates that this material consists of approximately 450,000 pages and would take one employee over 1 1/2 years to search. Mr. Hardy indicates that such an undertaking would be unprecedented and could negatively impact his office’s ability to carry out other obligations.”

Trentadue is questioning whether the bureau in fact has several sets of files—the main case file and others. In an affidavit from an earlier case, FBI agent Ricardo Ojeda, who was assigned to investigate the bombing, said the bureau kept what it called “zero files” on important cases. These, Ojeda said, were “reports containing information the FBI would not generally want disclosed to the defense and which were kept separate from a specific case file. These files were kept internally within the bureau and typically were not turned over to the prosecution or the defense.” When the FBI assigned numbers to its files, Ojeda said, “a zero after that number would mean that the report should go into the ‘zero’ file.”

The FBI has long sought to hide certain files, according to a recent investigation by the Center for Public Integrity. In the ’70s there were “June” files, which in the 1990s became the “zero” files. In 1996, the zero files were upgraded to the “I-Drive” files. Trentadue’s most recent search unearthed yet another secret set of files dubbed “S-Drive.” Judge Waddoups ordered the bureau to say whether the I-Drive and S-Drive data-storage areas had been searched for the videotapes and other documents—and if not, why not. The feds responded that the I-Drive no longer exists, and it has no reason to think the S-Drive would contain anything of value.

Trentadue is now preparing his latest brief, in which he will ask the judge to hold the bureau in contempt of court.