<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/un_photo/6025434303/">Stuart Price/UN</a>/Flickr

Eastern Africa’s worst drought in 60 years has combined with political violence in Somalia to produce what the United Nations is calling the “worst humanitarian disaster” in the world. But if you haven’t heard of the millions across Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia, and Djibouti who are malnourished, starving, and displaced, it’s because practically no one is talking about it. How did the famine start in the first place? Why is it so severe this time? And why are the international media largely ignoring this disaster? Let Mother Jones bring you up to speed on what’s happening in the Horn of Africa.

JUMP TO:

- The basics

- What makes a famine a famine?

- How bad is it really? The famine by the numbers (plus: map).

- What caused the famine, and why is it so bad?

- Why are the mainstream media ignoring this story?

- How do politics in Somalia impact the famine?

- How bad is the drought? (Plus: map.)

- Does the drought have ties to climate change?

- What’s being done to help?

- Whom to follow for more coverage

- Selected photos of the crisis

Want to know more about the famine and its causes? Email your question to the author, soltman [at] motherjones [dot] com, who will continue to update this page.

The basics: The Horn of Africa, which borders Kenya and includes Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Somalia, has long been prone to droughts and the famines that accompany them. But this year’s extreme drought, combined with skyrocketing food prices and violent political strife, has created what aid workers say is the worst food crisis in two decades, even worse than the 1992 famine in Somalia that killed 300,000 people. The United Nations first declared an official famine in two regions of Somalia on July 20. On September 5, the UN announced that famine had reached six regions and continues to spread.

The media’s relatively minimal coverage of the current famine has focused mainly on Somalia. But people are starving and displaced throughout the region, especially in Kenya, where massive refugee camps like Dadaab have swelled with Somalis desperate for food and medical help. The Nation reports:

At least 30,000 more refugees had arrived between June and July, roughly the number of people each camp was designed to shelter when they were first established in 1991. Now, around 440,000 people live in this camp built for 90,000.

More than 500,000 Somalis are displaced in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia. There, the situation is one of the most dire in Eastern Africa, as starvation has become just one of several threats to survival. CNN’s Cassandra Nelson reports:

Although it is famine that has forced so many people into Mogadishu for assistance, the growing concern is that those who make it here may be as likely to die of disease as starvation. Cholera and Acute Water Diarrhea (AWD) are taking the lives of hundreds of children…Thousands of cases of AWD/Cholera have already been confirmed at the main government hospital in Mogadishu.

What makes a famine a famine? Officially declaring a famine is serious business. Two days after the UN acknowledged the famine in Somalia, Secretary General Ban Ki-moon wrote: “We have resisted using the “f-word”—famine—but on Wednesday we officially recognized the fast-evolving reality. There is famine in parts of Somalia. And it is spreading.” Like many relief organizations, the UN doesn’t use the word “famine” lightly—it is reserved for only the most extreme food crises. BBC explains their how-bad-is-it criteria:

Most major aid agencies only describe a crisis as a famine when…at least 20 percent of the population has access to fewer than 2,100 kilocalories of food a day, [there is] acute malnutrition in more than 30 percent of children, [and there are] two deaths per 10,000 people, or four child deaths per 10,000 children every day.

Simply put, this famine is a real worst-case scenario for Eastern Africa.

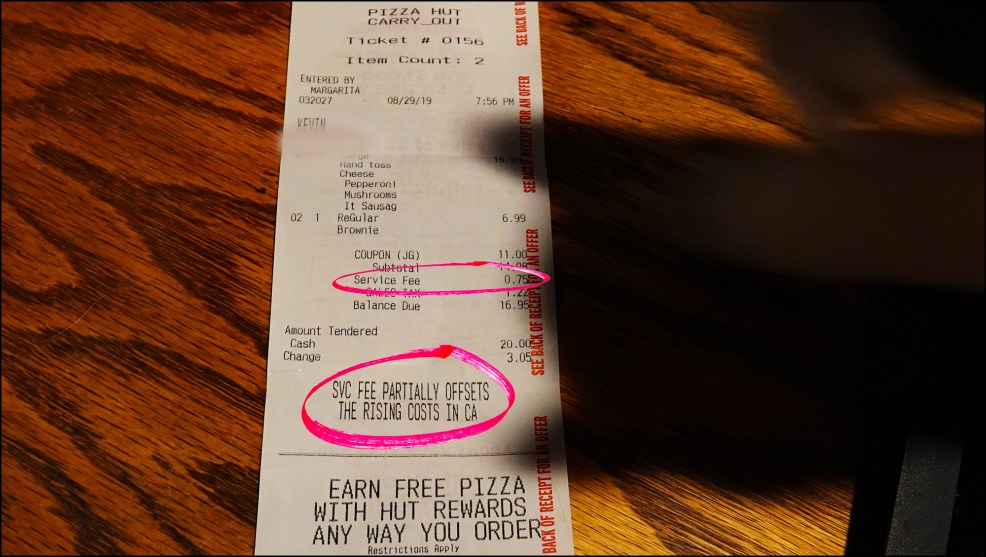

A map of where the famine is hitting hardest. Source: OCHAHow bad is it really? Here’s the famine by the numbers: Across the region, more than 12 million people risk starvation. In Somalia, 4 million people, or more than half of the population, are in crisis. Three million of them need immediate life-saving assistance, and 750,000 are at great risk of dying. In early August, a US aid official reported that more than 29,000 children in Somalia starved to death in three months; undoubtedly, more children have died since then.

A map of where the famine is hitting hardest. Source: OCHAHow bad is it really? Here’s the famine by the numbers: Across the region, more than 12 million people risk starvation. In Somalia, 4 million people, or more than half of the population, are in crisis. Three million of them need immediate life-saving assistance, and 750,000 are at great risk of dying. In early August, a US aid official reported that more than 29,000 children in Somalia starved to death in three months; undoubtedly, more children have died since then.

At least 250,000 people fled Somalia and are displaced. More Somalis, especially those living in the southern part of the country, would likely flee if they could, but many are trapped by political violence.

For more data, check out the UN’s breakdown of what’s going on in Somalia and whom it’s impacting.

To put some human faces to these daunting numbers, explore the Guardian’s interactive collection of famine refugees’ stories.

What caused the famine, and why is it so severe? The Horn of Africa’s famine isn’t just the weather’s fault. It has three main causes: drought, high food costs, and violent political instability. These are familiar factors in almost any famine, but this current crisis in East Africa is so dire because each of its causes is individually extreme.

Why are the mainstream media ignoring this story? A Pew Research Center study released in early September showed that news outlets barely noticed the famine relative to their other coverage: “In July and August the food crisis has accounted for just 0.7 percent of the newshole. Year-to-date the crisis registers at just 0.2 percent.” This is because US news coverage has been focusing on other topics—a tabloid scandal, Congress’ budget deficit battle, the economy, Middle East revolutions, and, most recently, Hurricane Irene. Some of these are important, attention-worthy stories, but they’ve drowned out almost any coverage of the famine. That matters: Relief organizations say their fundraising efforts have stalled because the media isn’t talking about the famine.

How much of an impact does Somalia’s political insecurity have on the famine? One of the most important—and underreported—causes of the famine is political violence and instability. The New York Times reports:

People are starving here, victims of Somalia’s famine, 70-pound adults and tiny babies with skin cracked like old paint. But there are few aid organizations around. They have been scared off by the hundreds of undisciplined militiamen, who constantly fire off their guns and have killed each other in recent weeks.

Somalia has not had anything resembling a stable central government since the 1991 civil war (also accompanied by a famine) when Siad Barre, its 22-year dictator, was toppled and replaced with the corrupt and ineffective Transitional Federal Government. Since then, fighting between the transitional government, war clans, and the al-Shabaab Islamist militia have left Somalia in a perpetual state of insecurity. The Guardian explains:

The extreme al-Shabaab militia…now controls most of southern Somalia. In 2009, it started expelling aid agencies from its territory, including the World Food Programme, and those organisations that remained were unable to use expatriate staff because of the security risks. Furthermore, the terror links meant that the US, the world’s biggest donor, was desperate not to allow any of its fund to get into al-Shabaab hands, so its aid funding to Somalia was significantly cut.

Even as the famine worsens and the death toll rises, al-Shabaab refuses to permit foreign aid groups to deliver aid in areas where its militia has control. The Financial Times reports:

Somali security forces briefly detained two Turks on Tuesday who went to an al-Shabaab area to deliver food to famine sufferers, and prevented others along with a group of journalists from doing so later in the week…Aid agencies say they have been unable to reach more than 2m Somalis facing starvation in rebel-held territories.

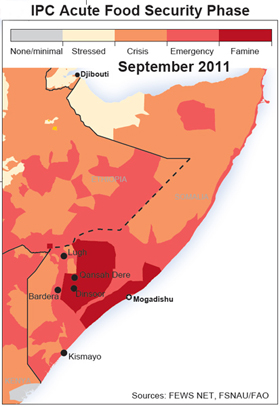

How bad is the drought? Eastern Africa experienced a drought last year, too, and food prices were already higher than usual. But this year, the drought was worse. ClimateWatch magazine explains:

Rainfall in the area generally comes in two seasons: the “short rains” of October-December and the “long rains” of March-June…Between October and December 2010, rainfall accumulations were several hundred millimeters below the long-term average…Rain shortfalls were more severe and widespread in the long rainy season. The failure of two consecutive rainy seasons decimated vegetation, including food crops and pasture for livestock.

Maps of the drought. Source: ClimateWatch

You can also watch the Horn of Africa’s drought worsen from space.

You can also watch the Horn of Africa’s drought worsen from space.

The region got its first good news in months on September 6, when the World Meteorological Organization predicted that southern Somalia, where the famine is most severe, should experience normal rainfall conditions during the September to December season. However, the WMO warned that drought would probably not improve significantly because conditions have been so bad for so long.

Why was the drought so severe in the first place? Does it have ties to climate change?

As always, the debate about how much climate change is affecting our planet rages on. But back in 2009, Gordon Conway, the chief scientist at the UK’s Department for International Development, warned that Africa was headed towards disaster. His studies showed the continent was heating up faster than the rest of the globe, and this warming would plague an already insecure continent with more severe and more frequent droughts and famines.

Chris Funk, a leading climate researcher on Eastern Africa, predicted this drought before it happened. He agrees that the region’s increasingly drastic droughts are caused, at least in part, by global warming trends affecting the entire planet, and says the problem will only get worse. The Huffington Post reported:

Funk, as well as others in his field, saw the potential for trouble in Somalia long before everyone else did. And he has come to the conclusion that back-to-back droughts that have devastated Somalia in the past year are likely part of a larger trend connected to global warming.

As if in response, the World Bank said on September 13 that the upcoming climate change talks in Durban, South Africa, must focus the connections between climate change and Africa’s droughts and famines. The Associated Press reported:

“The challenges are overwhelming,” Andrew Steer, the World Bank’s special envoy on climate change, said. “Africa needs to triple food production by 2050,” he said. “At the same time, you’ve got climate change lowering average yields…So, of course, we need something different.”

What’s being done to help? The UN says it needs $2.5 billion to properly respond to the growing crisis, but so far, the agency has raised 62 percent of its fundraising goal. Just under $1 billion is still needed. Explore the Guardian’s weekly updated Datablog for breakdowns of the famine’s fundraising data and details about how much has been raised, who’s donating, and where the money is going. Also see Financial Tracking Service’s continually updated spreadsheet of the Horn of Africa’s funding status.

However, as Dr. Unni Karunakara, the international president of Doctors Without Borders, pointed out in the Guardian, financial assistance is not the single magical solution to the Horn of Africa’s complex famine crisis:

“MSF [Médecins Sans Frontières] is constantly being forced to make tough choices in deploying or expanding our activities, in sticking to our principles of neutrality with the daily realities of people going without healthcare, without food. Our staff face being shot. But glossing over the man-made causes of hunger and starvation in the region and the great difficulties in addressing them will not help resolve the crisis. Aid agencies are being impeded in the area.”

Karunakara criticized other aid agencies for fundraising without telling donors that there’s a good chance their money will never reach the most desperate victims of the famine. As it is, he fears many of the Somalis most vulnerable to starvation are almost impossible to help.

Who to follow for more coverage: Use Twitter to follow #HornOfAfrica, #famine, #Somalia, or #drought. You can also follow the Guardian’s East Africa correspondent, Xan Rice, who is tweeting and reporting from the region. ABC’s David Muir is covering and tweeting about the crisis and Kenya’s Dadaab refugee camp. The Guardian has a section devoted to coverage of the famine. The New York Times’ East Africa bureau chief Jeffrey Gettleman is also writing extensively about the worsening famine and its causes.

Here are photos of the crisis:

On the edge of the Dadaab refugee camp, a young girl stands amid the freshly made graves of 70 children, many of whom died of malnutrition. Andy Hall/Oxfam/Flickr

On the edge of the Dadaab refugee camp, a young girl stands amid the freshly made graves of 70 children, many of whom died of malnutrition. Andy Hall/Oxfam/Flickr

A Somali woman in Mogadishu hands her severely malnourished child to a medical officer of the African Union Mission in Somalia. Stuart Price/UN/Flickr

A Somali woman in Mogadishu hands her severely malnourished child to a medical officer of the African Union Mission in Somalia. Stuart Price/UN/Flickr Ambia Mohammed’s daughter died after making the journey from Somalia to the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. Now Ambia must care for her grandchildren alone. Andy Hall/Oxfam/Flickr

Ambia Mohammed’s daughter died after making the journey from Somalia to the Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya. Now Ambia must care for her grandchildren alone. Andy Hall/Oxfam/Flickr

A starving and dehydrated child at Banadir Hospital in the Somali capital Mogadishu. Stuart Price/UN/Flickr

A starving and dehydrated child at Banadir Hospital in the Somali capital Mogadishu. Stuart Price/UN/Flickr

New arrivals at Dadaab wait to be registered, but many face a wait of more than six weeks. In the meantime they receive food rations that will last 21 days at most. Andy Hall/Oxfam/Flickr

New arrivals at Dadaab wait to be registered, but many face a wait of more than six weeks. In the meantime they receive food rations that will last 21 days at most. Andy Hall/Oxfam/Flickr

Many refugees seek shelter on the outskirts of Dadaab because the main camps are overcrowded. Andy Hall/Oxfam/Flickr

Many refugees seek shelter on the outskirts of Dadaab because the main camps are overcrowded. Andy Hall/Oxfam/Flickr A mother and her starving and dehydrated child lying at Banadir Hospital in Mogadishu, where more than 500,000 displaced Somalis seek aid. Stuart Price/UN/Flickr

A mother and her starving and dehydrated child lying at Banadir Hospital in Mogadishu, where more than 500,000 displaced Somalis seek aid. Stuart Price/UN/Flickr

Want to know more about the famine and its causes? Email your question to the author, soltman [at] motherjones [dot] com, who will continue to update this page.