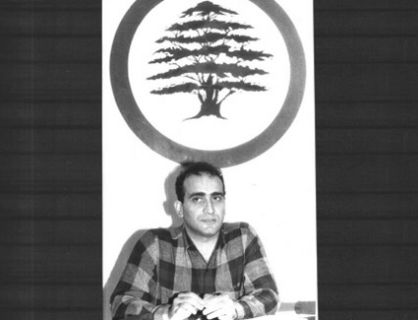

Walid Phares lecturing in front of a Lebanese Forces banner in 1986Photo courtesy of An-Nahar

Walid Phares, the recently announced co-chair of GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney’s Middle East advisory group, has a long résumé. College professor. Author. Political pundit. Counterterrorism expert. But there’s one chapter of his life that you won’t find on his CV: He was a high ranking political official in a sectarian religious militia responsible for massacres during Lebanon’s brutal, 15-year civil war.

During the 1980s, Phares, a Maronite Christian, trained Lebanese militants in ideological beliefs justifying the war against Lebanon’s Muslim and Druze factions, according to former colleagues. Phares, they say, advocated the hard-line view that Lebanon’s Christians should work toward creating a separate, independent Christian enclave. A photo obtained by Mother Jones shows him conducting a press conference in 1986 for the Lebanese Forces, an umbrella group of Christian militias that has been accused of committing atrocities. He was also a close adviser to Samir Geagea, a Lebanese warlord who rose from leading hit squads to running the Lebanese Forces.

Since fleeing to the United States in 1990, when the Syrians took over Lebanon, Phares has reinvented himself as a counterterrorism and national security expert, traveling comfortably between official circles and the GOP’s anti-Muslim wing. In a little over two decades, he’s gone from training Lebanese militants to teaching American law enforcement and intelligence officials about the Middle East, and from advising Lebanese warlords to counseling a man who could be the next president of the United States.

“I can’t think of any earlier instance of a [possible presidential] adviser having held a comparable formal position with a foreign organization,” says Paul Pillar, a 20-year veteran of the CIA and a professor at Georgetown’s Center for Peace and Security Studies. “It should raise eyebrows any time someone in a position to exert behind-the-scenes influence on a US leader has ties to a foreign entity that are strong enough for foreign interests, and not just US interests, to determine the advice being given.”

Phares has long faced questions about his background with the Lebanese Forces. As sketchy details have trickled out, he’s tried to downplay his involvement, claiming that he was “politically in the center” of Lebanese Christian politics and that he “was never a military official.” But a Mother Jones investigation has found that he was a key player within the Lebanese Forces when it was involved in a bloody sectarian conflict.

Lebanon’s civil war, which raged from 1975 to 1990 and claimed the lives of more than 100,000 people, ravaging a cosmopolitan society in the heart of the Arab world, is one of the great tragedies of a region that has experienced more than its share. Lebanon was granted independence by France in 1943, giving Christians an enclave of influence in the region. But by the mid-1970s the growth of the Muslim population and the presence of armed Palestinian Liberation Organization groups within Lebanon’s Palestinian refugee camps turned the country into a powder keg, as Christians tried to maintain their political dominance and Muslim and Christian militias battled for control of the country. The bloodshed was exacerbated by the interventions of regional powers like Israel and Syria, each trying to ensure their preferred factions would emerge victorious.

There were idealists and opportunists, thugs and honorable people on all sides of the war. But frequently these factions were clashing over no more than turf, money, or influence, with no quarter asked and none given.

“The Lebanese civil war really began as a series of tit-for-tat massacres between the right-wing Christian militias in Lebanon and the various Palestinian groups,” says the Center for New American Security’s Andrew Exum, a military expert who studied in Beirut. “No party to the Lebanese civil war comes out of that conflict with its hands clean; virtually all parties to the conflict were involved in some sort of massacre and some sort of atrocity.”

In 1978, the Lebanese Forces emerged as the umbrella group of the assorted Christian militias. According to former colleagues, Phares became one of the group’s chief ideologists, working closely with the Lebanese Forces’ Fifth Bureau, a unit that specialized in psychological warfare.

Régina Sneifer, who served in the Fifth Bureau in 1981 at the age of 18, remembers attending lectures where Phares told Christian militiamen that they were the vanguard of a war between the West and Islam. She says Phares believed that the civil war was the latest in a series of civilizational conflicts between Muslims and Christians. It was his view that because Christians were eternally the victims of Muslim persecution, the only solution was to create a national home for Christians in Lebanon modeled after Israel. Like many Maronites at that time, Phares believed that Lebanese Christians were ethnically distinct from Arabs. (This has since proven to be without scientific basis.)

Sneifer, now an author in France who wrote a 1995 book detailing her experiences in Lebanon’s civil war, recalls that in his speeches, Phares “justified our fighting against the Muslims by saying we should have our own country, our own state, our own entity, and we have to be separate.”

That ideology, some experts say, helped rationalize the indiscriminate sectarian violence that characterized the conflict. “There were lots of horrendous, horrendous atrocities that took place during that civil war, in part fueled by that fairly hateful ideology,” says a former State Department official and Middle East expert.

The most well-known of those atrocities was the Lebanese Forces’ massacre of hundreds, possibly thousands, of Palestinian refugees in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps in West Beirut in September 1982. The Israeli military, which was backing the Christian militias, was present but did not intervene to stop the bloodshed. Phares was never a fighter, and he did not participate. “I can assure to you [Phares] never shot one bullet in his life,” says Toni Nissi, who worked with Phares at the time. “He was an ideological man; he was a thinker.”

According to Sneifer, Phares’ close ties to Afif Malkoun, the head of the Fifth Bureau at the time, ensured that Phares’ ideas were widely disseminated among militants and students. But Phares’ influence grew even further with the rise of Samir Geagea, a former medical student turned Christian militia leader whose hard-line views jibed with his own.

Geagea’s ruthlessness was well known. He led a team of Christian militiamen who, in 1978, killed Tony Frangieh, a political rival of Geagea’s boss. According to contemporary press reports and Thomas Friedman’s 1989 book, From Beirut to Jerusalem, Geagea’s team didn’t just kill Frangieh and his bodyguards. They also murdered his wife, four-year-old daughter, and the family dog. (Mother Jones contacted a US-based representative of the Lebanese Forces political party but was unable to obtain an interview with Geagea.)

“Mr. Phares was aware of the crimes of Samir Geagea and he was still close to him,” Sneifer says.

The rivalries between Christian militia leaders were sometimes just as heated as the war’s sectarian skirmishes. After Geagea ousted a rival in a bloody coup and became the head of the Lebanese Forces in January 1986, Phares, according to an official Lebanese Forces announcement, was appointed to the group’s new executive committee, handling “expatriates affairs.”

“The executive committee was in charge of [the] Lebanese Forces,” explains Elias Muhanna, a Lebanon expert who’s currently a visiting scholar at Stanford University’s Program for Arab Reform and Democracy. “It would be like being elected to the board of trustees of a company or the top level leadership of a political party.”

Phares continued to play a prominent role in the ideological training of Lebanese Forces fighters. Geagea wanted to professionalize the militia, so he established a special school where officers would receive training not only in military tactics, but also in ideology. The various Lebanese factions were already sectarian in character, but Geagea, whom Nissi says used to read to his troops from the Bible, wanted religion to become an even more prominent part of the Lebanese Forces. For that he turned to Phares.

“[Samir Geagea] wanted to change them from a normal militia to a Christian army,” says Nissi, Phares’ former associate. “Walid Phares was responsible for training the lead officers in the ideology of the Lebanese Forces.”

Phares and Geagea ultimately grew apart, associates say, fueled by the latter’s decision to accept a Syrian-sponsored accord to end the war that curtailed the political power of Lebanon’s Christians and paved the way for Syrian occupation. That development led to a vicious inter-Christian battle between Geagea and his main rival, General Michel Aoun, which devastated Christian-majority areas of Lebanon that until then had largely avoided the war’s worst fighting. (Geagea is now part of the anti-Syrian faction in the Lebanese parliament.)

Despite the bloody fighting among Christians, the lesson that many Lebanese Christian exiles took from the war was that Islam was to blame for the destruction that ensued. “There is a problem with Islam…If you want to follow the Koran by the book you have to be like [Osama] bin Laden,” says one former Lebanese Forces militiaman. “It is a reality. And Walid Phares knows this reality. He’s lived here.”

The Lebanese civil war created an exodus of Christians who had served on the losing side. But for many of them, though the war had been lost, “the cause”—the fight for self-determination for Lebanese Christians—was not. Like other former militants and exiles, Walid Phares formed an advocacy group, the World Lebanese Organization, pushing for Western pressure on Syria on behalf of Lebanese Christians.

“It was an effort to project a particular sectarian political line and to do so with the aura of being representative of all the Lebanese,” says James Zogby, president of the Arab American Institute, himself a Maronite Christian of Lebanese descent. “It has a particular agenda in Lebanese politics, and [Phares] has brought that agenda here where it nicely fits with a neoconservative agenda.”

In 1993, Phares secured a position as a professor of Middle East studies and comparative politics at Florida Atlantic University. But as head of the WLO, one of his main projects was attempting to convince Israel to continue supporting the South Lebanon Army, a Christian-led militia fighting the Iranian-trained, Syrian-backed terrorist organization Hezbollah in a still-occupied area of southern Lebanon. Phares hoped to create a new Christian enclave in mostly Shiite southern Lebanon, where human rights groups were accusing the Israelis, the SLA, and Hezbollah alike of killing and displacing civilians.

“The only entity which can revive a credible Christian resistance, allied with Israel, is a nationalist group, based in the security zone,” Phares wrote in a 1997 article for the Ariel Center for Policy Research, a right-wing Israeli organization. “The Christians of Lebanon are the only potential ally against the advance of the northern Arabo-Islamic threat against Israel.”

Phares, in trying to pressure Israel to keep backing the SLA, worked with former militia leader Etienne Sakr, also known as “Abu Arz” (or “Father of the Cedars”). They, along with other Lebanese expatriots, “were working towards getting Syria’s occupation out of Lebanon and disarming [the] terror group Hezbollah,” Sakr says. During the civil war, Sakr headed the Guardians of the Cedars militia, described as an “extremist Christian group” by a 1993 State Department Report. In 1982, Sakr had held a press conference to defend the Sabra and Shatila massacres, calling the Palestinians a “cancer” on Lebanon. Forced into exile by the Syrian-dominated government at the end of the war, Sakr was convicted in absentia of spying for the Israelis.

The WLO’s advocacy was ultimately unsuccessful, and Israel withdrew from South Lebanon in 2000. Says Nissi: “How do you turn a Shiite Muslim area into a Christian area? It was a stupid idea, and they spent a lot of money and efforts on nothing.”

According to Phares’ former associates, the group fell apart due to infighting.

After the 9/11 attacks, an entire anti-Islam industry rose up on the right, with some conservatives advocating the view that the West was locked in a global, civilizational conflict with Islam. Phares’ years of advocacy had already won him friends on the American right, and he soon was in demand as a television analyst.

Appearing on Fox News two months after the attacks, Phares warned of the danger posed by Arabic-language news network Al Jazeera, telling Bill O’Reilly that “linguistically, the Arabic language is a very powerful one. It has a lot of codes. It could be used in a lethal way.”

Phares obtained a fellowship at the conservative Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a teaching position at National Defense University. He became a trainer at the Center for Counterintelligence and Security Studies, a nongovernmental organization that claims to have “trained over 75,000 Intelligence Community, Military, Law Enforcement, Homeland Security, Government and Corporate employees over the past 14 years.” Phares has testified before Congress and advised the Department of Homeland Security. Two of his books, 2005’s Future Jihad: Terrorist Strategies Against America and 2007’s The War of Ideas: Jihadism Against Democracy, were included on the congressional GOP’s 2007 summer “reading list.”

Phares’ message, though more polished, isn’t all that different from the paranoid worldview of anti-Muslim figures in the United States. In Future Jihad, Phares writes that “jihadists within the West pose as civil rights advocates” working to ensure that “[a]lmost all mosques, educational centers, and socioeconomic institutions fall into their hands.” Phares contends these stealth jihadists are merely waiting for a “holy moment” to strike.

“[Phares] is telling people to suspect all Muslims Americans as something other than how they portray to themselves,” says Thomas Cincotta, one of the authors of a report titled “Manufacturing the Muslim Menace,” published by the liberal group Political Research Associates. But it’s not just anyone Phares is preaching his ideas to. “He’s addressing the intelligence community, he’s addressing policymakers, military personnel,” Cincotta notes.

Phares eventually came into Mitt Romney’s orbit. Shortly after President Barack Obama won the election in 2008, Toni Nissi says Phares told Nissi over dinner at Washington’s Madison Hotel that Romney had promised Phares a high-ranking White House job helping craft US policy in the Middle East should the ex-governor win in 2012.

Mother Jones contacted Phares several times seeking comment. Eventually Jed Ipsen, a spokesman for Phares, offered to answer written questions on Phares’ behalf. Mother Jones provided him with a detailed list of queries, but Phares never responded. Romney’s camp also declined to respond to repeated requests for comment.

One former US counterterrorism official says he was shocked to learn that Phares was advising Romney. “He’s part of the same movement as Pamela Geller,” the official says, referring to the anti-Muslim conservative activist behind the Ground Zero mosque controversy. “He’s viewed as a mainstream scholar of jihadism, but he doesn’t know a lot about the actual movement.”

Phares may be viewed as mainstream, but he doesn’t avoid the more vocally anti-Muslim segments of the right. He has been a columnist for David Horowitz’s arch-conservative Frontpage magazine, and he endorsed two books by Robert Spencer, whose writings frequently posit that American Muslims are part of a conspiracy to establish Taliban-style Islamic law in the United States. Phares also serves on the advisory board of the Clarion Fund, which has released a series of films warning of an Islamist fifth column in the United States. In a YouTube video released by anti-Islam activist Brigitte Gabriel, herself a Maronite Christian whose views of Islam were shaped by harrowing experiences in Lebanon’s civil war, Phares tells Gabriel that “there is a cold war infiltration acquiring influence and the lands of what they call the infidels.” When Gabriel’s cohost asks Phares for examples of this vast conspiracy, Phares quietly assures him, “We can’t give names, because it’s operational, it’s happening now.”

“His experience in the region is colored by his experience in Lebanon during the civil war,” says Mohamad Bazzi*, an Adjunct Senior Fellow for Middle East Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations who emigrated to the United States from Lebanon in 1985. “He has this alarmist tendency, especially about Islam, to demonize all forms of political Islam, even ones that are not violent.” He adds, “To have someone who has these old ideas about the dangers of Islam and especially the dangers of political Islam—I don’t think it’s going to be very helpful to Romney’s understanding of the Middle East.”

Should Phares’ militant past keep him from advising a presidential candidate, or perhaps a president? “I wouldn’t want to be held responsible for everything I did when I was 22. I don’t think that’s fair to him,” says Graeme Bannerman, a Lebanon expert at the Middle East Institute and a former Republican staffer on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. “The question is what are his views now, and those fall well within the mainstream of the Republican Party.”

Phares is in many ways the ideal Republican foreign policy adviser, synthesizing all of the GOP’s foreign policy impulses in one place. He is supportive of American military intervention and combines anti-Muslim sentiments with a veneer of counterterrorism expertise drawn from his experience in Lebanon’s civil war.

But James Zogby asks: “Is he serving Mitt Romney, or is he serving the politics of a group in Lebanon that was fighting for their sectarian hegemony in a civil war that took over 100,000 lives?”

*an earlier version of this piece misspelled Mohamad Bazzi’s name as Mohamad Baazi.