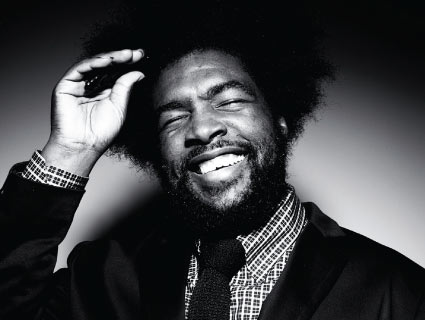

Photo credit: Ann Summa

Nowadays, nobody blinks an eye when hip-hop artists sample backwoods folkies and bands use multiple hyphens to describe their sound. But back in the ’80s when Fishbone, a black punk-funk-ska band, hit the LA music scene, no one quite knew what to make of their uncategorizable blend of styles and influences. Their unique sound, hyperactive live shows, and magnetic stage presence won them a fervent fan base, a record deal with Columbia, and an appearance on Saturday Night Live.

At the height of their popularity, Fishbone was the hottest band in SoCal, beloved by fans, admired by peers, and name-dropped by celebrities (Tim Robbins wore a Fishbone shirt in Bull Durham, as did John Cusack in Say Anything). The band seemed to be on the verge of mainstream success. But their big break never came. While bands that bore Fishbone’s influence, including No Doubt and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, rose to fame and fortune, Fishbone struggled with the usual challenges of moderate success—addiction, clashing egos, struggles to preserve their integrity—and a few unusual ones: religious conversion, kidnapping charges, and people not quite knowing what to make of them.

Yet while Fishbone faded from the spotlight, they never stopped making music—and now they’re the subject of a new documentary, Everyday Sunshine, directed by Lev Anderson and Chris Metzler. Narrated by Laurence Fishburne, the film follows the band from its members’ meeting on the newly integrated playgrounds of Southern California through its rise to semi-stardom, slow decline, and near-dissolution. Along the way, animated segments depict the sociopolitical context of the time; the likes of Gwen Stefani, Flea, and Branton Marsalis testify to Fishbone’s influence, and clips of the band’s early live shows convey Fishbone’s energetic charisma and musical chops.

I sat down with bassist Norwood Fisher and frontman Angelo Moore and Everyday Sunshine‘s co-directors to chat about the making of the film, a lifetime on the road, and how they managed to land such an appropriately named star narrator.

Mother Jones: How did you decide the world was ready for the first Fishbone documentary?

Lev Anderson: I don’t know if the world was ever ready for the first Fishbone documentary. I was kind of a fan of the band as a kid growing up, but we just saw it as an opportunity to tell a fun story. I love music and history and art and politics, and with a band like Fishbone, that kind of just all comes together. Especially with the sociopolitical issues of a black punk rockers coming out of LA at the time. So that just seemed like an interesting story to start with, and then once we dug deeper there was a lot of other stuff going on.

MJ: You mentioned the mix of history and politics, and the documentary talks about the politics of the Reagan era. What’s the place for Fishbone in the current political moment? If punk was the music that emerged from the backdrop of the ’70s and ’80s, what is it now?

Norwood Fisher: Punk rock is still there! The Occupy movement is pretty punk rock.

Angelo Moore: Yeah, Occupy is pretty punk rock.

NF: Might be a marriage of hippies and punk rockers. We’ll see what the next batch of 16-year-olds come up with, but I think it’s gotta have an attitude.

AM: As far as I’m concerned, ever since, like, 1998 we’ve been living in the Dark Ages. Even though I consider President Obama a beam of bright positive light, you have a lot of forces around him that are just dark, ignorant, medieval-type forces trying to drown out any possibilities of something different. Some of my lyrics used to be about society and government and stuff like that, my concerns, or disgust or whatever—but now it’s just so ridiculous I can’t even write anything about it.

LA: I think a band like Fishbone has managed to remain relevant because they speak to issues that people experience in their lives. You saw that reflected in the Jimmy Fallon thing with Michele Bachmann, where 25 years after a song has been recorded, the Roots decided to make their own kind of statement. And it’s not like “Lyin’ Ass Bitch” was such a punk rock song, but I think its attitude and the band’s legacy sort of reinforces its appropriateness.

NF: Coming of age in the 1970s, there’s an amazing amount of influence from comic areas that had political bite or social relevance. You look at what made a guy like Richard Pryor funny, it was his insight into the human condition. He could take a painful situation and make it funny. He was a huge influence on me. And we grew up reading Mad magazine and National Lampoon and [stuff with] the comedy of a Saturday Night Live. You know, it was silly but it had a political bite. It was political satire. And so that’s something that was a part of us. We had as much fun as we could but it was fun that was influenced by those things. And honestly, what Questlove did with bringing “Lyin’ Ass Bitch” to the Jimmy Fallon Show, that was a great National Lampoon moment. It was political satire. [See MoJo‘s interview with Questlove here.]

Chris Meltzer: Fishbone’s kind of universal, unique, and timeless. The band has always been labeled kind of a party band because of the fun sound of their music and what a good time you can have at their shows, but there’s always been this social and political subtext to their songs. So we could showcase over the past 30 years, busing and desegregation issues in the 1970s, punk rock, the gang problems and crack epidemic in the 1980s, the election of Ronald Reagan, and then the kind of alternative scene—all these things you could see through Fishbone’s eyes. It’s a historical film but also a film about the creative process and how those events shape each other.

MJ: There is a lot of political history in the documentary, but I was also struck by the changes in the music industry. Because Fishbone never got that big record deal, you were basically surviving on touring, but now that the big labels are collapsing, everyone’s starting to do that. Having lived it for a couple of decades, do you think it’s sustainable?

NF: You gotta have what it takes. In the current paradigm, a guy like Sammy Davis Jr. would still be king because he can hit the stage and deliver. A guy like Michael Jackson—hit the stage, deliver. But it’s the mediocre stage show that might have a harder time. A band like Fishbone, we come with an explosive live show, and we survive.

CM: When you go to a Fishbone show, more than likely Angelo’s going to be out in the crowd beforehand hanging out, because that’s what he enjoys doing. And they go out and they sign autographs and merchandise, but they’re not doing it out of, Oh my god, I need to do it, but because they’ve always liked to break down the barrier between what’s going on stage and what’s going on in the crowd. From an outsider’s perspective that’s where they really thrive and that’s where I think some of those creative juices seem to flow from. There’s a lot of creativity that burgeons forth from that need to always keep on swimming.

LA: There is a little bit of parallel there between the film and the music in that, you know, we don’t have an advertising budget. We screened in all the film festivals and you get all the local media talking about your film at the local level and it’s like a band going out on tour in a way.

NF: Yeah, knowing you had elegantly strolled down Haight Street and put posters up your goddamn self—that’s pretty goddamn punk rock. (Laughs.) I’m looking at it like it’s an amazing opportunity. We came from a time where artists got hardly anything on the record deal and now people are making deals where you split the proceeds 50-50. Whereas we signed to a major label at age 19, and those are our records that are our classic records, and after that we moved more towards the independent realm with each successive record. It was punk rock and it was hip-hop in the 1970s that said you can do this, anybody can make this kind of music. And the internet came along and made that more possible.

MJ: So having a good live show is what makes it possible to survive, but it seems pretty grueling—how do you keep up the pace?

AM: It can be grueling, all the tours and live shows, but at the same time, it’s really gratifying to be able to get out of you all the music art and passion, you got a chance to get that out.

NF: And if it’s you being honest, it’s not a grueling thing. It’s about honesty, at the end of the day. If I see Tom Waits I do not expect him to turn a backflip, you know what I mean? I love Kate Bush, what do I expect from her? Just to be Kate Bush.

MJ: So what else do you listen to—what new artists do you like?

NF: There’s a band called Pour Habit that I really love. They’ve got an awesome energy and they’re making punk rock that bites. There’s a band called Cerebral Ballzy that I like, another punk-rock, South Central LA band that’s coming up. There’s a band called Viva Voce out of Portland that I like a lot.

NF: You know, it took me a long time to actually get dubstep, but it makes me laugh. You know, the wobbly bass thing, and the kind of, you know, the straight damage sound of the base, I love that thing. It’s got a little Flipper. I’ve gotta figure out how I can use that to my advantage as bass player.

AM: I like DJ Skrillex. I like that video he’s got out. It’s like a new form of reggae, psychedelia, rock—when I hear that womp-womp-womp, I think about Bootsy [Collins], I think about Flipper, that heavy bass, that distorted bass. Oswald! Now that was dubstep. Pre-dubstep. Someone probably listened to that and said I’m gonna put that in the time capsule and come out with it five years later. Bam, you got dubstep.

CM: One of the things we’ve been asked while making the film is, do you think that if Fishbone came out today, they would be more commercially successful? And it’s really a chicken-and-egg question because you wouldn’t have today without a band like Fishbone laying the groundwork for this kind of style 30 years ago. The number of musicians that we’ve met of many different generations that have attributed their sound or style to these guys—we knew there were a lot of bands influenced by Fishbone, but until we really dug into it we didn’t know how far-reaching it was.

MJ: Yeah, it was really interesting to hear all these famous artists talk about how they saw or heard Fishbone and then went out and formed a band—it reminded me of that thing Brian Eno supposedly said about the Velvet Underground. What was it like to hear people talking about how you’d influenced them?

NF: It gave us an opportunity to actually reflect and see that as much as the difficulties of the journey and the lack of substantial monetary compensation were a reality, to hear all those people say “Fishbone is why I do it” or “Fishbone influenced me to do it harder, to dig deeper” it served to validate the journey.

CM: We didn’t want to make a hagiographic portrait of these guys. They’ve done a lot of wonderful things, but we wanted people to understand the sorts of sacrifices they made to achieve those things. Because those things don’t have value unless you understand what they gave up to make that happen. It gets painful sometimes but I think in the end it’s a kind of hopeful story about doing what you want to do and pursuing your path.

MJ: How’d you get Laurence Fishburne to narrate?

NF: Brendan Mullins was the booker at a club called Club Lingerie as punk rock was growing up, and Laurence Fishburne was a bouncer there. Brendan thought it would be a great idea to introduce Fishbone to Larry Fishburne. So we became friends and we kept in touch over the years.

CM: Lawrence told us that he felt a kinship to the band because being in Hollywood as an African-American entertainer, there weren’t a lot of great roles. I don’t know what he was in between Apocalypse Now and Boyz n the Hood. And he would talk about the outsiders club—he thought Fishbone were these black rock-n-rollers who were kind of uncategorized because no one knew how to classify them. So I think that was another reason he was attracted to the project.

Click here for more music features from Mother Jones.