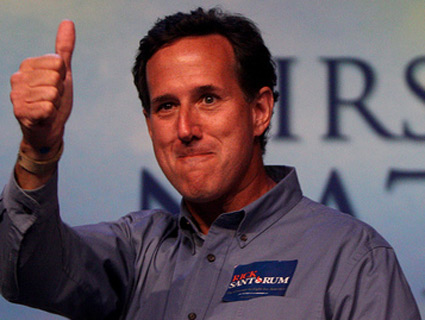

Rick SantorumAndrew A. Nelles/ZUMAPRESS.com

On the campaign trail, Rick Santorum has highlighted his track record of opposing campaign finance strictures. He hails the Supreme Court’s Citizens United decision that allows corporations and unions to spend unlimited funds on independent political ads and other messaging as “a return to ancient First Amendment principles.” He reminds voters of his Senate vote against the “oppressive” 2002 McCain-Feingold bill. But during his first Senate campaign in 1994, Santorum sounded much like a campaign finance reformer, advocating the type of restrictions he now says strangle free speech.

At the time, federal law capped political action committee contributions to candidates at $5,000 a year. Although hardline conservatives and libertarians opposed any restriction on PAC contributions, Santorum urged tougher limits on PAC donations during his bid to unseat Sen. Harris Wofford (D-Penn.).

In an October 1994 interview with a Pittston, Pennsylvania, TV station—the transcript of which was obtained by Mother Jones—Santorum called for lowering the PAC donation limit to $1,000. “I think that would reduce the cost of campaigns, because the availability of money just wouldn’t be there,” he said. It was a position Santorum had articulated as early as April 1994, according to opposition research records and news clips compiled by Wofford’s campaign and the state Democratic Party.

Santorum’s position on PACs put him at odds with conservative GOPers in the Senate. Led by Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), those conservatives in 1994 torpedoed a major campaign finance reform bill, a decade in the works, that would have reduced the PAC contribution limit, though not by as much as Santorum proposed. (Santorum spokesman Hogan Gidley did not respond to a request for comment.)

Santorum also proposed requiring that at least half of every congressional candidate’s campaign funds come from within his or her district. The goal of his campaign finance reforms, Santorum told the Johnstown Tribune-Democrat in 1994, was to “make sure that people in your district are the folks who not only elect you but folks who finance your campaign, [and] that we don’t have an undue influence from Washington, DC, and the big PACs.”

Another reason Santorum cited for curbing the influence of special interests was that he believed PACs favored incumbents: “They give them the money which insures that they are going to win.”

When he was elected to the Senate, Santorum quickly warmed up to the perks of incumbency, and his campaign finance stance shifted dramatically. Amidst outrage over the Democratic fundraising abuses of the 1996 presidential election (including allegations of illegal foreign donations), Santorum voted in March 1997 against a bipartisan measure co-sponsored by fellow Pennsylvania GOP Sen. Arlen Specter that would let Congress control federal campaign spending and permit states to set fundraising and spending limits in state and local campaigns. Years later, during his second term in the Senate, he voted against the McCain-Feingold bill that limited so-called “issue advocacy” ads and banned soft money—unlimited and unregulated corporate and union cash contributed to both parties.

As a senator, Santorum formed two leadership PACs, Fight-PAC and America’s Foundation, which together doled out $986,595 to GOP candidates between 1998 and 2006. Santorum himself raked in $8.9 million in total PAC contributions throughout his congressional career—85 percent of it from business PACs.

Now, on the presidential campaign trail, Santorum has PACs to thank for keeping his insurgent campaign alive. The Red, White, and Blue Fund and Leaders for Families, both of them super-PACs, have together spent $2.9 million supporting Santorum and attacking his opponents. Much of the cash has come from a few heavyweight donors, including conservative financier Foster Friess.

The “undue influence” of PACs, Santorum may now be thinking, is not so bad after all.