<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/cat.mhtml?lang=en&search_source=search_form&version=llv1&anyorall=all&safesearch=1&searchterm=brain+mri&search_group=&orient=&search_cat=&searchtermx=&photographer_name=&people_gender=&people_age=&people_ethnicity=&people_number=&commercial_ok=&color=&show_color_wheel=1#id=27953882&src=a7c3be14c0b3584a3250939f99b06c83-1-2">psamtik</a>/Shutterstock

You’ve probably heard by now that an outbreak of fungal meningitis caused by contaminated steroid injections has killed 20 people and sickened 257 more as of Wednesday. The contaminated steroid—injected into the spine as a routine treatment for back pain—originated at the New England Compounding Center (NECC) in Massachusetts.

The deadly outbreak has also exposed lax oversight of compounding pharmacies, which fall into the hazy area between federal and state laws. Lawmakers are now calling for tougher regulation of these facilities that mix and distribute drugs. Past attempts at regulation have been stymied by lobbying and opposition from the compounding pharmacy industry.

So what is meningitis?

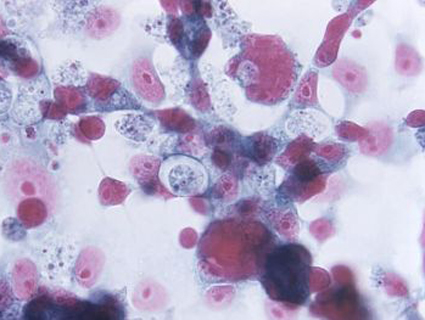

Meningitis is an infection of membranes around the brain and spinal cord. It’s usually caused by bacteria or viruses, but fungi are at the root of this outbreak. Left untreated, the fungal infection can cause strokes and brain damage. The good news: fungal meningitis is not contagious.

Who got the contaminated steroid injections?

The outbreak has been traced to three lots of methylprednisolone acetate administered between July 30 and September 18, and the CDC estimates some 14,000 patients may have been exposed. On Monday, the FDA announced it was also looking into possible contamination of two other products from the same company: another injectable steroid called triamcinolone acetonide as well as cardioplegic solution, which is used in open heart surgery.

Symptoms of fungal meningitis take one to four weeks to appear. According to the CDC, symptoms including new or worsening headache, fever, sensitivity to light, stiff neck, weakness, and numbness.

The CDC has a map of states that received the contaminated steroid as well as a comprehensive list of health clinics that administered it.

Meningitis cases as of 10/18. CDC

Meningitis cases as of 10/18. CDC

Where did the fungus come from?

The CDC and FDA are still investigating. In the meantime, New England Compounding Center has issued a voluntary recall of all 1200 of its pharmaceutical products made in its Framingham, MA facility. An early report identified the culprit to be a common fungus called Aspergillus, but state health officials in Tennessesse have since zeroed in on another rarer fungus known as Exserohilum. State health commissioner Dr. John Dreyzehner called Exserohilum “a fungus so rare that most physicians never see it in a lifetime of practicing medicine.” Both fungi are common in the environment but don’t usually cause health problems.

What is a compounding pharmacy, anyway?

Compounding pharmacies mix and repackage drugs, but they are not registered or inspected as drug manufacturers. They originally filled a niche mixing drugs for local patients who needed unique doses or certain ingredients removed for allergies. However, as seen in the scale of the meningitis outbreak, some compounding pharmacies are selling nationally and in bulk. There are 3,000 compounding pharmacies in the US, nearly all of which have sprung up in the past decade. The executive VP of the International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists estimated that 10 percent are large-scale compounders like NECC. A number of their products are essentially cheaper versions of FDA-approved drugs, which probably accounts for their popularity.

The fungal meningitis outbreak is the deadliest associated with a compounding pharmacy, but it’s hardly the first. For example, deaths have been linked to a feeding solution contaminated with bacteria in 2011 and an improperly mixed toxic drug in 2007—both of which originated at compounding pharmacies.

Who regulates compounding pharmacies?

Good question. “The Food and Drug Administration has more regulatory authority over a drug factory in China than over a compounding pharmacy in Massachusetts,” a law professor told the New York Times. Because they’re registered as pharmacies rather than drug manufacturers, compounding pharmacies are subject to state rather than federal laws. This made sense when they sold their products locally, but less so now that some of their products are nationally distributed. The WSJ also reports that only 17 states have guidelines for compounding pharmacies.

Since the meningitis outbreak, Massachusetts’ Board of Registration in Pharmacy has taken the unusual step of asking for signed affidavits from all compounding pharmacies in the state swearing they do not mass produce medications.

So the FDA is asleep at the wheel again?

To its credit, the FDA was onto this problem 15 years ago. Testifying on the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997, former FDA commissioner David Kessler asked Congress for the authority to regulate compounding pharmacies. The law passed, but those provisions were struck down by the Supreme Court in Thompson v. Western States Medical Center. The case was brought by seven compounding pharmacies who claimed that provisions about advertising in the law violated their First Amendment rights.

In the FDA compliance guidelines (pdf) published after the case in 2002, the agency said:

FDA believes that an increasing number of establishments with retail pharmacy licenses are engaged in manufacturing and distributing unapproved new drugs for human use in a manner that is clearly outside the bounds of traditional pharmacy practice and that violates the Act… Some “pharmacies” that have sought to find shelter under and expand the scope of the exemptions applicable to traditional retail pharmacies have claimed that their manufacturing and distribution practices are only the regular course of the practice of pharmacy. Yet, the practices of many of these entities seem far more consistent with those of drug manufacturers and wholesalers than with those of retail pharmacies. For example, some firms receive and use large quantities of bulk drug substances to manufacture large quantities of unapproved drug products in advance of receiving a valid prescription for them. Moreover, some firms sell to physicians and patients with whom they have only a remote professional relationship.

Since 2001, the International Academy of Compounding Pharmacies has spent $1.1 million lobbying Congress. Its newsletter, according to the WSJ, bragged about how they defeated a 2007 draft bill that would have given the FDA control over compounding pharmacies

Was NECC breaking any state laws?

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health said that NECC was violating the requirements of its state license. The agency did not specify how, but emails obtained by Reuters show the company soliciting bulk orders without individual patient prescriptions, which is a violation of requirements in some of the states where it sent drugs.

In 2006, the FDA sent a warning letter to NECC citing the company for violations that included illegally manufacturing a numbing cream. (While the FDA has no oversight of a compounding pharmacy’s everyday operations, it can intercede when it gets complaints about companies that are illegally acting as manufacturers.) A former FDA official told the Times such letters were common, and compounding pharmacies usually complied after a warning.

Why are people talking about Senator Scott Brown?

The Republican senator, who’s in a tight reelection race against Elizabeth Warren in Massachusetts, got about $10,000 in donations from a NECC exec’s fundraiser. In addition, Brown, along with 10 other senators, signed a letter in July asking to relax rules for pharmacies doing bulk sales of controlled substances. (The steroid is not controlled substance, but this would loosened regulations over many of NECC’s 1200 other products.) The campaign had tried to mitigate the bad press by donating the $10,000 to the Meningitis Foundation of America.