View from the 05 Deck on USCG icebreaker Healy on 15 October 2012: Julia WhittyThis was the view at sunrise from the 05 deck five levels above the main deck of the Coast Guard icebreaker Healy three weeks ago. (For more about this science cruise check out my Arctic Ocean Diaries.) It was a balmy 27°F (-2°C). On the same cruise last year temperatures fell to -20°F (-29°C). Last month the ocean was relatively calm. There wasn’t much of anything to indicate we were actually in the Arctic. It looked a lot like South Pacific sunrises I’ve watched from open boats in a shorty wetsuit. Frankly it was creepy.

View from the 05 Deck on USCG icebreaker Healy on 15 October 2012: Julia WhittyThis was the view at sunrise from the 05 deck five levels above the main deck of the Coast Guard icebreaker Healy three weeks ago. (For more about this science cruise check out my Arctic Ocean Diaries.) It was a balmy 27°F (-2°C). On the same cruise last year temperatures fell to -20°F (-29°C). Last month the ocean was relatively calm. There wasn’t much of anything to indicate we were actually in the Arctic. It looked a lot like South Pacific sunrises I’ve watched from open boats in a shorty wetsuit. Frankly it was creepy.

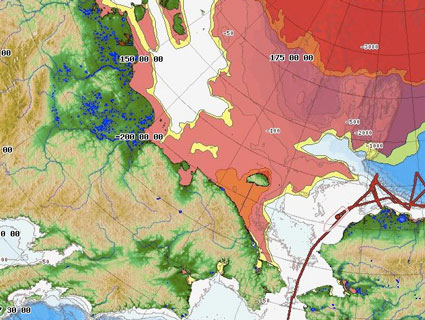

Arctic sea ice extent for October 2012 was 2.7 million square miles (7 million square kilometers). Magenta line shows 1979 to 2000 median extent for October. Black cross marks geographic North Pole. Yellow names mark the seas of the Arctic Ocean: National Snow and Ice Data Center

Arctic sea ice extent for October 2012 was 2.7 million square miles (7 million square kilometers). Magenta line shows 1979 to 2000 median extent for October. Black cross marks geographic North Pole. Yellow names mark the seas of the Arctic Ocean: National Snow and Ice Data Center

Yesterday the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) released their monthly overview of Arctic sea ice for October 2012, which explains a lot of what I saw. The map above shows October 2012 ice in white, compared to the median sea ice extent from 1979 to 2000 (pink line). Here’s what the NSIDC report says:

Average ice extent for October was 7.00 million square miles (2.70 million square miles). This is the second lowest in the satellite record, 230,000 square kilometers (88,800 square miles) above the 2007 record for the month. However, it is 2.29 million square kilometers (884,000 square miles) below the 1979 to 2000 average. The East Siberian, Chukchi, and Laptev seas have substantially frozen up. Large areas of the southern Beaufort, Barents, and Kara seas remain ice free.

That’s less ice in the Arctic this October than an area of Alaska and Texas combined.

My cruise covered the entire eastern extent of the Chukchi Sea and the entire southern extent of the Beaufort Sea. These are the Alaskan parts (and some Canadian parts) of the Arctic Ocean. The fact that they remain largely ice free even now could bode poorly for ecosystems accustomed to a cap of sea ice most of the year.

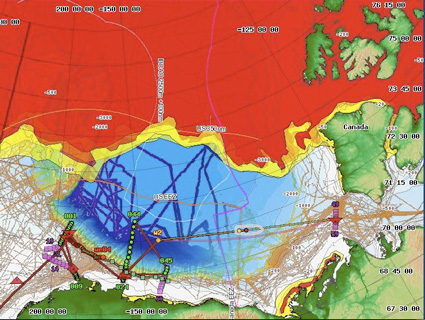

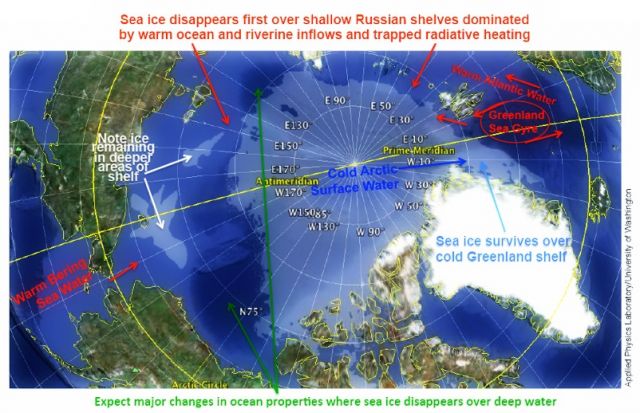

A snapshot of how ocean depth in the Arctic influences sea ice extent. Sea ice cover for 28 August 2012 is shown in semi-transparent white, ocean depths in blues, deeper blues indicating greater depth: National Snow and Ice Data Center courtesy Jamie Morison/Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington

A snapshot of how ocean depth in the Arctic influences sea ice extent. Sea ice cover for 28 August 2012 is shown in semi-transparent white, ocean depths in blues, deeper blues indicating greater depth: National Snow and Ice Data Center courtesy Jamie Morison/Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington

Really interesting in the NSIDC report is an analysis of what forces may affect sea ice formation:

Research by our colleagues Jamie Morison at the University of Washington Seattle and NASA scientist Son Nghiem suggests that bathymetry (sea floor topography) plays an important role in Arctic sea ice formation and extent by controlling the distribution and mixing of warm and cold waters. At its seasonal minimum extent, the ice edge mainly corresponds to the deep-water/shallow-water boundary (approximately 500-meter depth), suggesting that the ocean floor exerts a dominant control on the ice edge position.

They note that in some some cases sea ice survives even in shallower continental shelves because of water circulation patterns. The shelf of the Greenland Sea is nearly always ice covered because of southward-flowing Arctic currents that keep it cold. Meanwhile other shallow areas like the Barents and Chukchi seas lose their ice cover due to warm ocean waters and freshwater runoff from rivers—two forces that are increasing in strength as the land warms too.