In August 2012, as most members of Congress were hitting the campaign trail, three Republican lawmakers were enjoying an all-expenses-paid retreat at Ol Jogi, a private 66,000-acre ranch in Kenya’s lush highlands. This “African Versailles” features a golf course, racetrack, dozens of man-made lakes, around 120 miles of road, more than 200 major buildings, and some 350 employees. The representatives—including Alabama’s Jo Bonner, then the chairman of the House ethics committee—were ostensibly there to learn about threats to the ranch’s idyllic landscapes and herds of wild animals, which were made famous in the Oscar-winning 1985 film Out of Africa.

Ol Jogi is owned by a trust benefiting the Wildenstein family, a secretive, embattled Franco-American aristocratic line; the clan has been accused of buying art looted by the Nazis, among other misdeeds. Over five generations, the Wildensteins have amassed a fortune estimated to be worth as much as $10 billion by dealing art, breeding horses, and—according to French authorities—evading a reported $800 million in taxes. One family member received a multimillion-dollar mansion for her 17th birthday; another has spent millions on plastic surgery to make herself look more like a cat. Since 1990, the Wildensteins and a family firm have given nearly $150,000 to Republican candidates and campaign committees.

Given the family’s history of support for the party, it’s no surprise that Bonner, along with top GOP fundraiser Rep. Diane Black (R-Tenn.) and Rep. Kay Granger (R-Texas), chose to overlook their hosts’ legal difficulties and visit the site of Meryl Streep and Robert Redford’s African love affair. What’s more intriguing is who paid for the 10-day, $47,000 adventure for the legislators (as well as Bonner’s and Black’s spouses and Granger’s son): the International Conservation Caucus Foundation, a mysterious charity based out of a two-story townhouse in the posh Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, DC.

It may not have a glass-and-steel headquarters, but the ICCF counts among its supporters some of America’s most powerful corporations and special interests. The Nature Conservancy, Conservation International, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the World Wildlife Fund helped launch the group and are the only members of its Advisory Council. Meanwhile, the foundation’s Conservation Council includes ExxonMobil and six other Fortune 500 companies, as well as trade groups (like the American Petroleum Institute and the Malaysian Palm Oil Board) that represent environmentally destructive industries.

The ICCF’s mission statement says it aims “to advance US leadership in international conservation…and to develop the next generation of conservation leaders in the US Congress.” The group’s corporate backers, however, hear a different story. A company that supports ICCF gets “an unparalleled opportunity for access and visibility, to have its voice heard and its perspective appreciated by many of the most powerful leaders in Congress,” according to a confidential summary of the foundation’s schmoozing with lawmakers sent to members in September and obtained by Mother Jones.

The ICCF can offer donors this “unparalleled” access because a loophole in congressional travel and lobbying restrictions allows educational foundations to wine and dine lawmakers in ways lobbyists can’t. It has filed tax returns that contradict congressional ethics disclosures and failed to report key financial information, leaving the public in the dark about how it pays for expensive trips like Bonner’s.

What’s clear is that the ICCF provides polluters and their lobbyists entrée to a vast number of legislators: With 141 members on both sides of the aisle, the International Conservation Caucus, its bipartisan sister organization, is one of the largest of the hundreds of official congressional groups lawmakers have formed to pursue common goals and interests. (Other caucuses range from the obscure Contaminated Drywall Caucus to conservative Democrats’ Blue Dog Coalition.) Perks like exotic trips, opulent galas, and the opportunity to “work with”—and raise money from—”conservation-oriented corporations committed to policies of good stewardship,” as a letter sent to prospective members put it, have helped the ICC recruit fully a quarter of Congress: 117 representatives and 23 senators have joined.*

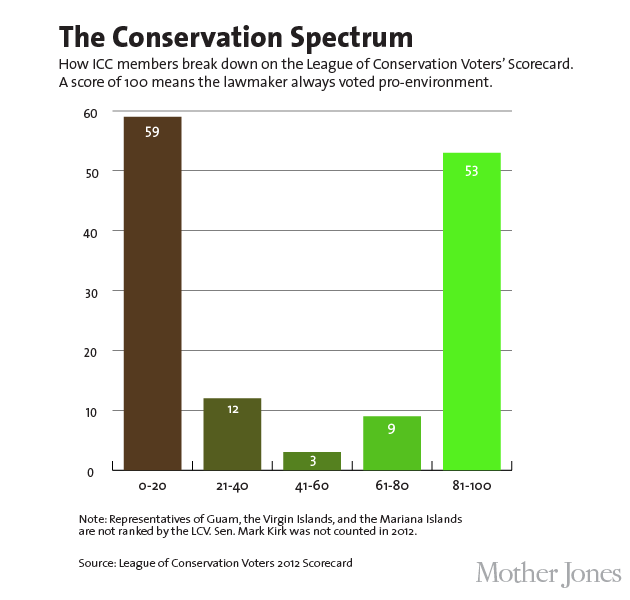

But in its work with lawmakers, the ICCF has been timid at best on conservation issues. The group is silent on climate change and rarely takes controversial stands. Its partners on Capitol Hill include Sen. James Inhofe (R-Okla.), whose staffers have gone on three separate ICCF-organized trips; Inhofe, a leading climate change denier, won the Center for Biological Diversity’s 2012 Rubber Dodo Award for his work to “drive endangered species extinct.” Sen. John McCain, (R-Ariz.) who earned a score of zero (out of 100) from the League of Conservation Voters in 2012, is also a member. House ICC co-chairman Ander Crenshaw (R-Fla.) and 40 other representatives in the caucus have LCV scores of 10 or less, as well.*

Also read: “The Totally Mediocre Conservation Caucus“

Why would green groups support an organization that works with polluting companies, the oil lobby, and anti-environment lawmakers? The answer has a lot to do with funding. Massive conservation organizations like those on the foundation’s Advisory Council struggle to sustain budgets that can reach nearly a billion dollars a year. They don’t raise that kind of money with small donations; they must aggressively pursue multimillion-dollar corporate contributions and government grants. In this pursuit, the ICCF plays a crucial role.

As in most exclusive clubs, the perks the foundation offers rise with the size of the contributions. ICCF membership—which starts at $25,000, tax-deductible—includes tickets to inside-the-Beltway events hosted by the foundation; there’s an annual Congressional Oyster Roast & Frogmore Stew, and past galas have featured British Prime Minister Tony Blair, Mexican President Felipe Calderón, Edward Norton, and Harrison Ford. For an additional $25,000, partners can host congressional coffee briefings, luncheons, and dinners, where lawmakers can learn about, for example, Walmart’s “Commitment to Sustainability” or the “Oil and Gas Industry’s Investment in Conservation.” There are also unspecified extra perks for partners who pay for the copyrighted $100,000-per-year “Teddy Roosevelt Steward” designation. John Gantt, the foundation’s president, says the top contributors get “additional seats at major events,” but declined to provide more details.

When Tony Blair and Indiana Jones aren’t enough, the ICCF woos lawmakers by taking them on “educational field missions.” Since December 2007, it has led 39 Republican and 26 Democratic aides and lawmakers on 10 group trips at a cost of more than $350,000. In addition to Bonner’s Ol Jogi visit, the foundation has organized excursions to Botswana, Tanzania, South Africa, Brazil, and Costa Rica. One outing, a $30,700, 10-day tour of Botswana and South Africa that Rep. John Carter (R-Texas) and his wife took in August 2011, was the second most expensive on record for any member of Congress. “This is not educational,” says Craig Holman, a lobbyist with the watchdog group Public Citizen. “This is influence peddling available primarily only to special interests that have a lot of money to throw around.”

Update: LCV’s 2012 lawmaker scores and the 2013 ICC membership list were not available until after this story went to press. Three members of the House ICC are representatives of US territories and a fourth member is a chaplain. Neither the representatives from US territories nor the chaplain vote on legislation. The web version has been updated to reflect the latest data. Click here to return.

??This sort of congressional junket was supposed to have ended five years ago, when legislation passed in the wake of the Jack Abramoff scandal strictly limited lobbyists’ and companies’ ability to pay for congressional travel. But in the years since, the congressional ethics committees that enforce those rules have decided the post-Abramoff restrictions do not extend to charities—even those, like the ICCF, that get much of their funding from lobbyists and organizations that lobby. This loophole has allowed outside funding for congressional travel to return to levels not seen since Abramoff’s globe-trotting prime, when “Casino Jack” famously took ex-Rep. Bob Ney (R-Ohio) on a Scottish golfing junket that would eventually help land them both in prison. In 2011, the most recent year for which there is data, $5.8 million was spent on 1,600 privately funded congressional trips—money that is often funneled through groups like the ICCF.

Leading many ICCF field missions is founder David Barron, a former aide to President Ronald Reagan and onetime national chairman of the Young Republicans. (Read the full interview with Barron.)”He is the face of ICCF and also puts a lot of work into it,” says a former GOP staffer who’s gone on an ICCF-organized trip and attended some of its DC luncheons and dinners. Barron, who stepped down as president in 2009 and no longer collects a salary, “continues to exercise responsibility for ICCF’s direction and recruit new members” for the ICC, according to the foundation’s website. “I was very much part of getting the ICCF started,” Barron says. “I’m delighted to offer a little advice and support occasionally, but I’m doing other things. I’m not ICCF anymore.” Gantt says the ICCF “generally” pays Barron’s expenses when he travels with the foundation, which Barron says he does only “when our schedules overlap.”

Barron’s decision to downplay his continued involvement might stem from his colorful history. His official ICCF bio describes him as a “conservation volunteer…who had been working in Africa for many years on issues of democracy and development” before he launched the foundation in February 2006.

Barron did have years of experience on the continent, but he wasn’t always working for democracy or conservation. For more than a decade, Barron, business partner Jeffrey Birrell, and the employees of Barron-Birrell Inc. provided lobbying, public-relations, and consulting services for a succession of West African dictators, starting in 1992 with the government of Nigeria’s General Ibrahim Babangida. In 1995, the company worked for the regime of Sani Abacha, the brutal military leader who had overthrown Babangida’s hand-picked successor and would later order the execution of Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other nonviolent environmental activists. Barron says he “worked for Nigeria,” not Abacha, and “never met the man.”

Birrell refused to comment. But years of contracts and reports Barron-Birrell filed with the Justice Department indicate that, in the early 2000s, the men moved into “environmental consulting services”—code for helping African countries land international conservation grants. In September 2002, the Republic of Congo paid the firm $100,000 for aiding “discussions involving environmental conservation of the Congo Basin.” That same month, Omar Bongo, the kleptocratic president of Gabon from 1967 until his death in 2009, inked a similar $400,000-per-year deal with Barron-Birrell for advice on “economic development, environmental conservation, and other matters.” The Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations later accused Birrell of setting up a shell company to help Bongo buy US-built armored vehicles and military transport aircraft. Barron-Birrell had collected more than $1 million from Bongo by the time Barron launched the ICCF in 2006.

A year and a half later, post-Abramoff reforms prohibited lobbyists and registered agents of foreign governments from leading groups devoted to educating lawmakers. To continue running the ICCF, Barron needed to document that he was no longer employed by foreign regimes. In September 2007, four days before the new rules became law, Barron filed nearly a decade’s worth of backdated reports on his work for African governments and declared that Barron-Birrell had closed up shop.

Today, Barron says he is “spending a lot of time in Africa,” though he adds that he hasn’t been paid by “any government in quite some time.” But thanks to another legal loophole, if Barron were to do any lobbying during those travels, he wouldn’t have to disclose it—as long as he did the actual glad-handing abroad. The law designed to keep track of such influence peddling only applies to lobbying activities on American soil. Overseas, representatives of foreign governments “can meet with [lawmakers] as much as they want and don’t have to report it,” explains Ben Freeman, a national-security investigator at the Project on Government Oversight.

Some uncertainty surrounds the financing of ICCF trips and events. When I sent the foundation’s tax returns to Marcus Owens, a Washington lawyer who ran the IRS division charged with supervising tax-exempt organizations, he noticed an “audit issue”: The ICCF’s filings in 2010 and 2011 list no payments for public officials’ travel. But congressional ethics filings say that the ICCF helped fund 24 overseas trips for lawmakers, their staffs, and their families during that period. The discrepancy indicates the “ICCF is lying to somebody,” Owens argues. “They’re telling Congress one thing; they’re telling the IRS another.”

Following my inquiries, the ICCF moved to correct its two most recent tax returns. “There has been absolutely no attempt to provide less than full disclosure for all reportable expenses for educational field missions involving participating officials,” Gantt says. The foundation’s accountants, Berlin Ramos & Co., claim they “misinterpreted the instructions” when they filed those “incorrect” returns.

The foundation’s audited financial statements could help explain the reason for the contradictory filings. The ICCF’s tax returns say it makes these statements “available to the public upon request.” But although I requested them six weeks before this story went to press, Gantt never provided the financial documents. That lack of disclosure worries Owens. What the group has released so far doesn’t offer “a particularly clear snapshot of what the organization does,” he says. “There’s something else going on here.”

Accounting issues aside, the ICCF has unquestionably succeeded in delivering benefits for its partners—including the four green groups on its Advisory Council. Working with Barron and the ICCF has opened doors. “They have been able to be a platform for some environmental groups to get in front of an audience that normally they would never have,” says the ex-GOP staffer.

That exposure helps the four groups collect tens of millions of dollars in government grants—for everything from improving conservation efforts in the Dominican Republic ($10 million) to minimizing the impact of coffee growing in Central America ($1.5 million)—every year. The ICCF also encourages member corporations to spend on conservation. Its glossy Partners in Conservation annual reports are replete with environmental projects funded by polluting corporations and administered by big green groups. The 3M Foundation, for example, touts the $21 million it has donated since 2001 to projects like Conservation International’s forest restoration work in southwest China and the Nature Conservancy’s efforts to protect savanna grasslands in Australia. Back home, though, 3M is fighting a lawsuit from Minnesota’s attorney general to force the manufacturing giant to pick up the tab for a toxic chemical cleanup that could cost up to $1 billion.

Given its work with polluting corporations and anti-environment politicians, it’s perhaps no surprise that the ICCF is careful to avoid important, politically charged conservation issues. “They have not taken any aggressive or controversial stands at all,” the former GOP aide notes. “In fact, that’s something that they really emphasize when they start off and try to explain themselves to a new member.” A 2011 letter recruiting lawmakers to join the ICC promised that it “does not take positions on specific legislation.” That’s even the case when ICC members have sponsored legislation that directly contradicts its stated goals: The ICCF highlights its commitment to end poaching, but neither the caucus nor the foundation spoke up when nearly 20 ICC members tried to roll back a law that punishes companies caught importing illegally harvested fish, animals, or plants.

Climate change may be the most significant threat to the environment, but the ICCF avoids mention of it. “We’ve always been agnostic about” global warming, says Adam Brooks, the group’s communications director. “It’s just not something we discuss because of the sensitivity of our audience.” That might be tactically smart—as Glenn Hurowitz of the Tropical Forest and Climate Coalition notes, “There are certain members of Congress for whom mentioning climate change ends the conversation.” But it’s strategically shortsighted, warns Kierán Suckling, the executive director of the Center for Biological Diversity. Hobnobbing with oil executives and providing “green cover” to anti-environment lawmakers signals that the conservation community “is not serious enough about climate change to hold everybody accountable,” Suckling says. Environmental groups “have been fooled into thinking that the access that they get is actually influence. At the end of the day, they’re the ones that are influenced.”

Representatives from the four conservation organizations allied with the ICCF defend their ties; both the Nature Conservancy (where I interned in college) and Conservation International told me they were not aware of Barron’s past work.

In any case, the ICCF and its junkets are likely to remain a presence on Capitol Hill. In December, Bonner, the outgoing ethics committee chairman and Ol Jogi guest, announced new congressional regulations after a three-year review of privately sponsored travel. In a joint statement signed by Bonner and Linda Sánchez (D-Calif.), the top Democrat who green-lighted Bonner’s Kenyan adventure and many other ICCF junkets, the committee said it “gave significant consideration” to the question of nonprofit organizations funded by lobbyists and groups that lobby. In the end, the committee did not see a way to limit perks from nonprofits “with legitimate interests in providing appropriate fact finding opportunities to Members of Congress.” I asked Bonner what made the Ol Jogi trip “appropriate,” but he never responded.