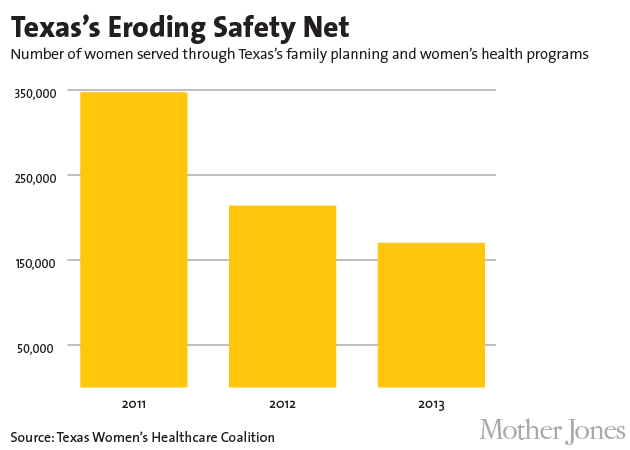

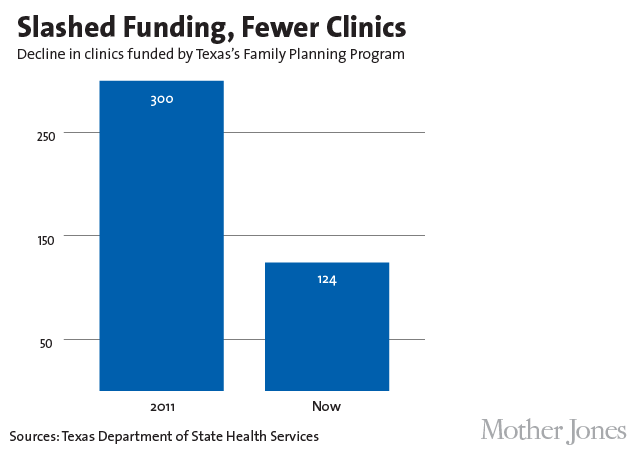

In the past two years, Texas legislators slashed funds for family planning and passed up $30 million a year in federal Medicaid money, largely to squeeze Planned Parenthood out of the state’s women’s health programs. Last week, hundreds gathered at the south steps of the Texas State Capitol in Austin to protest the resulting public health mess: Researchers say nearly 200,000 Texas women have lost or could lose access to contraception, cancer screenings, and basic preventive care, especially in low-income, rural parts of the state. I reported from the rally:

Given that anti-choice legislators in other states could draw inspiration from Texas’s “winning” strategy to defund Planned Parenthood—several have tried and failed in recent years—it’s worth surveying the damage.

About a year after Texas slashed its family-planning budget by two-thirds, with 50 clinics shutting down as a result, the Texas Policy Evaluation Project surveyed 300 pregnant women seeking an abortion in Texas. Nearly half said they were “unable to access the birth control that they wanted to use” in the three months before they became pregnant. Among the reasons: cost, lack of insurance, inability to find a clinic, and inability get a prescription. The state’s health commission says Texas will see nearly 24,000 unplanned births between 2014 and 2015 thanks to these cuts, raising state and federal taxpayer’s Medicaid costs by up to $273 million.

In a state where half of all pregnancies were unplanned in 2011, and 1 in 3 women of childbearing age lacks health insurance, this is only going to get worse.

The Planned Parenthood clinics that anti-choice legislators booted from the state’s Women’s Health Program serviced nearly 50 percent of the program’s patients. Along with contraceptive counseling, the clinics provided basic screenings for cancer, hypertension, and other key problems. There’s no shortage of need: women in Texas suffer high rates of STIs and unintended pregnancies compared to national figures, and the state ranks 50th for diabetes prevalence in women. Nonetheless, Republican lawmakers went after the clinics in 2011, thanks to their long-standing beef with the organization, and forfeited tens of millions in Medicaid reimbursements to the Women’s Health Program so they could defund Planned Parenthood clinics without breaking any federal rules governing how states have to spend Medicaid money.

Despite losing its highest-volume providers, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission insists the revamped, wholly state-run and state-funded Women’s Health Program can reshuffle all the displaced patients and keep providing the same levels of care as before. But last October, researchers at George Washington University examined five Texas counties and found that in order to effectively replace Planned Parenthood, other clinics would need to increase their caseloads two to five times.

That seems unlikely. The remaining clinics are already straining under these changes, according to a survey by the Texas Policy Evaluation Project. More than a fifth have reduced their hours of operation, while others, like Planned Parenthood in East Austin, are staying shakily afloat on community donations. Instead of offering IUDs, a highly effective birth-control method with higher up-front costs to the provider, clinic staffers are now more likely to offer lower-cost birth control pills. They also tend to give out fewer packs of pills per visit, making it harder for patients to be consistent. Others are seeing fewer patients or increasing their fees.

Lone Star Circle of Care, for example, lost 62 percent of its Title X funding over the last year. Now it’s charging more patients a $20 to $35 fee for an annual exam. That’s still low, in part because Lone Star isn’t affiliated with an abortion provider and therefore hasn’t lost funding altogether. At Planned Parenthood clinics in Texas, on the other hand, the same exam can now cost nearly $100; before defunding, they were virtually free.

“If you put fees in place, even if they’re pretty modest, patients just don’t come in, or they don’t come in as often,” says Sarah Wheat, vice president for community affairs at Planned Parenthood of Greater Texas. “We’ll have patients who, if they had a high gas bill that month, or a high electricity bill, they’ll think, ‘Okay, well maybe next month I can go in.’ Or they’re going to say, ‘Let me just get the gonorrhea test. I’ll pay for the chlamydia test next time.'”

It’s hard to tell whether displaced patients are finding care elsewhere. After Hill Country Community Action announced it was closing its family planning clinics in the central Texas town of San Saba last summer, only a hundred or so of its 2,000 clients called to ask about other providers, the Texas Observer reports. Many of the remaining clinics in the area are charging new fees since the cuts, and none reported an uptick in new patients from San Saba, except for the Planned Parenthood in Waco.

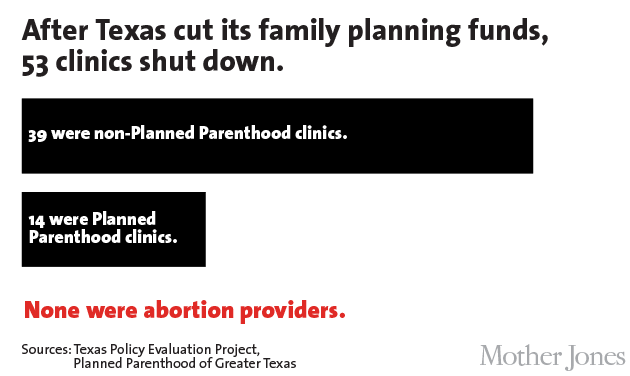

Meanwhile, anti-choice legislators are touting these cuts as a way to wipe out the “abortion industry,” but it turns out none of the 53 clinics that closed since September 2011 were providing abortions to begin with. None of the Planned Parenthood clinics formerly involved with the Women’s Health Program provided abortions, either—Texas has never allowed abortion clinics to participate in WHP. And under the Hyde Amendment, public health providers can’t use federal funding to administer abortions, anyway. “Ironically, this whole conversation is about abortion services, and yet clinics providing abortions in this state were untouched by these cuts,” says Wheat.

In 2011, there were about 70,000 abortions in Texas, a 10 percent drop from 2010. But it’s too soon to know whether this is the result of the state slashing its family planning funds or other measures?, says Dan Grossman, vice president for research at Ibis Reproductive Health and a researcher at the Texas Policy Evaluation Project. What we do know, Grossman adds, is that most women showing up for abortions are not changing their minds after seeing their ultrasounds, as they’re now required to do in Texas.

It remains to be seen whether anti-choice lawmakers in other states will adopt Texas’s costly strategy for defunding Planned Parenthood within their own borders. Since 2010, nine states have tried to cut family planning funds; Montana, New Hampshire, and New Jersey have slashed their family planning budgets by more than half. Seven have made it harder for clinics like Planned Parenthood to receive state or federal family planning grants. Last month, four Planned Parenthood clinics in Wisconsin shut down in the face of cuts.

Now with the Texas Legislature back in session, some state senators are proposing to add $100 million back into the state’s primary care program, specifically for women’s health services; and last week a Democratic legislator introduced a bill to reverse the Affiliate Ban Rule. But Wheat says these measures are unlikely to repair the damage of the past two years.

“It’s hard to put back together a system that’s been dismantled,” she said.