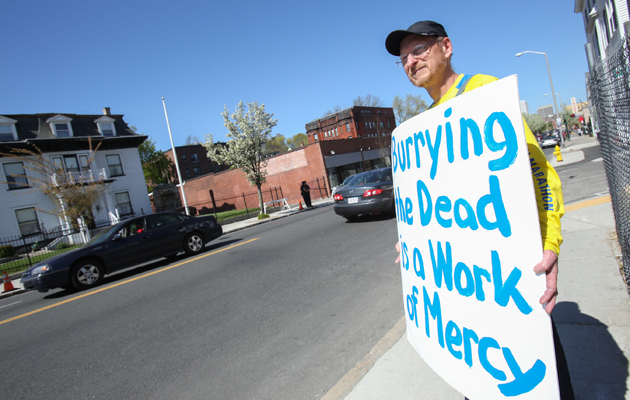

A protestor stands outside the Graham Putnam & Mahoney Funeral Parlor in Worcester, where Tamerlan Tsarnaev's body is being held.Nicolaus Czarnecki/Zuma

On Monday, Cambridge City Manager Robert Healy announced he would not grant a permit for the burial of Boston Marathon bomber Tamerlan Tsarnaev, citing his authority as “chief conservator of the peace within the city.” Instead, Healy argued, federal authorities should arrange the disposal of the body—preferably somewhere far away.

The response was mixed. The protesters who have gathered outside the funeral home where the body is being kept were no doubt encouraged. Gov. Deval Patrick called the burial a “family issue.” The family, for its part, had not even formally sought a burial permit in Cambridge. Tamerlan’s mother wants his body returned to Russia; his uncle, Ruslan Tsarni, wants the body to remain in the Boston area where he spent the last decade of his life.

Cambridge’s fight over the resting place of the older Tsarnaev brother is complicated by the fact that the remains of a Muslim cannot be cremated. “This is very unusual circumstances that make it really complicated and hard to think of another historical parallel,” said Gary Laderman, a professor at Emory University.

For the most part, says James Fox, a criminologist at Northeastern University, families of mass murderers have kept a low profile, opting to dispose of their relatives’ remains quietly, and often anonymously. Columbine shooter Dylan Klebold’s funeral was open to the press, but he was ultimately cremated. (The resting place of the other gunman, classmate Eric Harris, is unknown.) Virginia Tech gunman Sueng-Hui Cho is reportedly buried at an undisclosed location in Fairfax, Virginia.

“There have been mass murderers who have been buried in regular cemeteries,” Fox says. “Their names are on a tombstone. Their funerals are private, but they are buried.” But terrorism-related cases have often been viewed differently than other kinds of capital crimes. “This is not just about their crime. It’s their nationality and their ideology.”

One of the most high-profile cases of domestic terrorism prompted an anti-burial backlash. After Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was sentenced to death in 1997, Congress moved quickly to pass legislation preventing anyone who had been convicted of a federal capital crime from being interred in a veterans’ cemetery. McVeigh’s ashes were scattered.

No cemetery in the city of Chicago would allow the four men hanged for their role in the 1886 Haymarket Riot, in which seven police officers and four civilians were killed in a bombing, to be buried within the city limits. Instead, they were relegated to a plot in the suburb of Forest Park. Leon Czolgosz, the anarchist who assassinated President William McKinley, was dissolved in sulfuric acid, Breaking Bad-style, to prevent admirers from visiting his grave. Lee Harvey Oswald’s corpse was flipped from Dallas cemeteries like a hot potato before finally finding a resting place in Fort Worth.

Perhaps the most heated and prolonged burial battle involved the bodies of American cult members who died at Jonestown, Guyana, in 1978. As historian David Chidester explained in Salvation and Suicide, “Public officials had vehemently resisted any mass burial of the Jonestown dead for fear that such a burial site would become a cultic shrine.” Instead, the bodies languished at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware before arrangements were finally made for a group burial in Oakland, California.

A precedent for prohibiting a burial can even be found in Greek mythology. In the story of Antigone, Oedipus’ daughter seeks to obtain a proper burial for her brother, Polynices, after he had taken up arms against the city-state of Thebes. Polynices’ body was not allowed back inside the city and was to be left outside the limits, to be eaten by animals. Mourning his death was prohibited. (Antigone buried it anyway.)

Keith Eggener, a professor of art history and archeology at the University of Missouri, notes that there’s a certain irony in the recent history of banning bad guys from burial grounds. “Some archeologists believe that the first-known human burials,” he says in an email, “were granted only to social transgressors—the idea being to ostracize these individuals and keep them from returning to harm the living.”

When Cambridge’s Healy declared his city would not allow the burial of Tsarnaev, he struck much the same note. “The difficult and stressful efforts of the citizens of the city of Cambridge to return to a peaceful life would be adversely impacted by the turmoil, protests, and wide-spread media presence at such an interment,” Healy said in a statement. “The families of loved ones interred in the Cambridge Cemetery also deserve to have their deceased family members rest in peace.”