<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/gageskidmore/5438043026/sizes/l/in/photolist-9hxoJw-9huh7a-9hkGsE-9hxpi9-9hug9Z-9hhypT-9hugLp-9hhzAx-9hkFVs-9hhyYi-9hkHgf-9hhyPT-9hhzMx-9hxp4C-8XUr3X-82Zrii-82ZpbP-82ZqwX-7TKNP1-6UK8hh-8qmWKg-8qqcuu-8qn2r6-8qmTyg-7Gpvh6-e47zd7-e41Wmc-e47zX1-e47zLY-e47Bvw-e47z3j-e47zjG-e47zAG-e47BPA-e41YKt-e47APW-e41Ygk-e41YUR-e47Ax5-e47Ag3-e47zrL-e47ApJ-e47BEd-e47BY9-e47A67-e47AZQ-848b5x-c8UN1J-84bc6h-848366-84ba65/">Gage Skidmore</a>/Flickr

This story was updated after publication to include the CFPB’s comments.

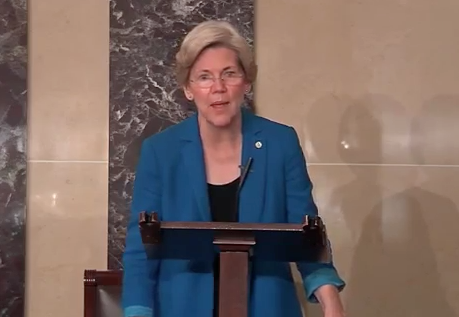

Last week, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) declared victory when the Senate confirmed Richard Cordray to head the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the consumer watchdog agency that Warren conceived and helped launch. For years, Republicans had been fighting tooth and nail to kill the infant agency, which is charged with protecting Americans from abusive practices by banks, payday lenders, mortgage-servicing companies, and debt collectors. Originally, the GOP planned to cripple the agency by blocking it from ever getting a director. That didn’t happen, so now Republicans have to turn to Plan B.

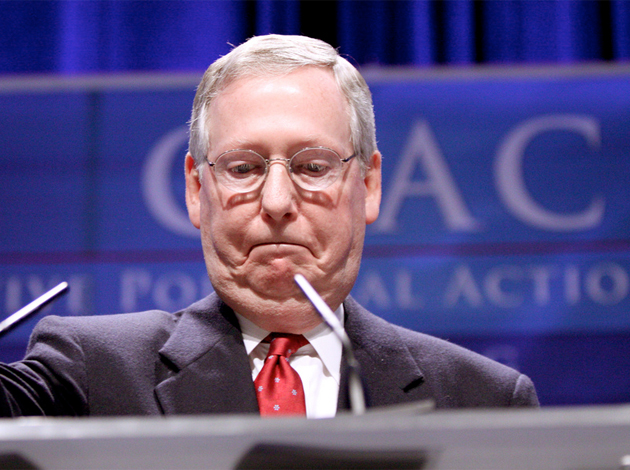

The GOP has several weapons in its arsenal, including a case against the agency that the Supreme Court will hear in the fall, a separate suit recently lodged against the bureau, several pieces of legislation that would weaken the CFPB, and a slew of bills that would clamp down on government regulators more generally. There’s just one problem: The plans are probably not going to work.

Plan B(1): Supreme Court case

The backstory: When President Barack Obama first nominated Cordray to head the CFPB, in July 2011, Republicans filibustered the nomination. That prompted Obama to use a recess appointment to install Cordray in the post six months later. (A recess-appointment is a presidential appointment that happens while the Senate is on vacation and does not require Senate approval.)

The plan: Republicans then backed a suit challenging the constitutionality of several of Obama’s recess appointments*. The CFPB is not party to the case, but the ruling will have bearing the legality of Cordray’s recess appointment too. The challenge has now reached the high court, which will hear the case this fall. The GOP is hoping that the court will say the appointments were unconstitutional—a ruling that could damage the legal underpinnings for regulatory actions the CFPB took before Cordray was finally confirmed.

The problem: Legal experts say that even if the court rules that Cordray’s recess appointment was unconstitutional, it is unlikely to weaken the CFPB’s authority. “He’s director now. I think most of what happens stays in place,” says Oliver Ireland, a partner in the financial services law firm Morrison Foerster. “It is possible that individual things could be overturned by a court,” he says, but adds that in other cases like this one in which companies challenge the authority of a federal agency, courts typically side with the government.

An unfavorable ruling could still be a bit of a headache for the agency. Hans Von Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation, says this type of decision could mean the CFPB has to run all of the rules it made under Cordray’s recess appointment through the rule-making process again, which could take months. A spokesperson for the CFPB responded that “We believe Director Cordray could ratify any act the bureau has undertaken to date.”

Plan B(2): Court Case #2

The backstory: Republicans have been making noise in recent weeks about the fact that the CFPB has swept up the credit records of some 5 million Americans in order to conduct surveys about the safety of various financial products on the market.

The plan: A case filed Monday in federal court could help the GOP cause. During a CFPB investigation of a California bankruptcy lawyer, the agency demanded vast swaths of data relating to her work from a company called Morgan Drexen, which provided her paralegal support services. Morgan Drexen filed suit, alleging that the CFPB’s data collection practices are illegal. The CFPB maintains that “We believe this work is within our authority and consistent with the ordinary course of a government investigation.”

The problem: A ruling in the case could take a while. The firm representing Morgan Drexen in the case does not know how soon a decision could be reached.

Plan B(3): Legislation

The backstory: Since 2011, 43 GOP senators have been pushing several specific structural changes to the CFPB, including subjecting the agency to the congressional appropriations process so that Congress can revoke its funding, and giving the agency a board of directors to curb Cordray’s power.

The plan: Republicans have introduced bills in both the House and the Senate that would make these changes. And a slew of deregulatory bills have been introduced in both chambers that would apply to all federal agencies, including the CFPB, making it harder for them to regulate. One bill would crimp rule-making agencies by making them consider the “indirect costs” of all regulations on small businesses, without defining “indirect cost.” Another would “totally remake regulatory process,” says Amit Narang, an expert on the federal regulatory process at the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, by adding tons of new analytical and procedural steps for each new rule created at all agencies. “This is really an attempt to try to gut agencies across the board, in the same way they’ve been trying to gut the CFPB since its inception,” Narang says.

The problem: In the Senate, which is controlled by Democrats, Republicans don’t have the votes for their more ambitious bills, explains Ross Baker, a professor of political science at Rutgers University. “I think it would be most unlikely,” he says. “They’re trying to do death of a thousand cuts on the agency but… I don’t think it will get very far.”

Von Spakovsky agrees. “Having anything happen is going to depend on… the 2014 elections,” he says, “And whether Republicans can take over the Senate and drive through legislation to change this.” But even if Republicans take control of the Senate in 2014, Obama will still be in the White House—and he has threatened to veto bills aimed at weakening the agency.

A few bills affecting the CFPB have the potential to garner a little more Democratic support, says Baker. One, which is co-sponsored by Democrats Gwen Moore (D-Wisc.), and Ed Perlmutter (D-Colo.), would subject the agency’s operations to more judicial review. Another would require the CFPB to get consumer consent before collecting Americans’ financial data. But neither would kneecap the agency the way blocking Cordray would have.

Baker predicts that Senate Republicans may pipe down about the CFPB because there’s little they can do to damage the agency without gaining control of the Senate and the White House. “I don’t see this as enough of an issue for [Senate] Republicans to unanimously rally around,” he says. Republicans have pledged to keep fighting, but at least for now, Warren and the Democrats have won.

*Correction: A previous version of this story stated that Republicans backed a suit challenging the constitutionality of Cordray’s appointment, implying that the CFPB was party to the case. It is not.