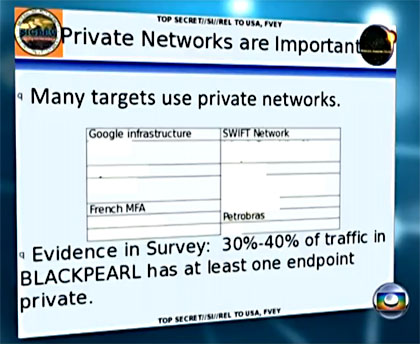

It seems that not a week goes by without a friendly reminder from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden that the government has found a new way to spy on us. From allegedly cracking online encryption, to paying US tech companies to build backdoors in their security systems, to spying on international bank transactions—it’s tempting to wonder whether there is any such thing as electronic privacy anymore. But in the last few months, Congress has introduced a spate of bills aimed at reining in the NSA’s vast surveillance powers.

These pending bills seek to keep the NSA from sweeping up phone records en masse, take the rubber stamp away from the top-secret spy court that approves surveillance requests, and allow tech companies to tell the public more about the government requests they receive for user data, among other things. (At present, no lawmakers are actually trying to defund the NSA, although GOP Rep. Justin Amash of Michigan gave it a good shot.) Here’s a guide to 12 pending bills that target US government spying (collected with help from the Electronic Frontier Foundation).

The Surveillance State Repeal Act (H.R. 2818)

Sponsor: Rep. Rush Holt (D-N.J.)

What it does: Unlike other pending bills that make careful revisions to existing surveillance laws, this one would completely repeal the PATRIOT Act and the 2008 amendments to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), the statutes from which the NSA draws its broad spying powers. The bill also amends FISA—the 1978 law that governs the collection of foreign intelligence information—to clarify that “no information relating to a United States person may be acquired pursuant to this Act without a valid warrant based on probable cause” and it decrees that the government can’t require tech companies to build backdoors in their security systems. In other words, this is Director of National Intelligence James Clapper’s worst nightmare.

The LIBERT-E Act (H.R. 2399)

Sponsors: Reps. John Conyers (D-Mich.) and Justin Amash (R-Mich.),

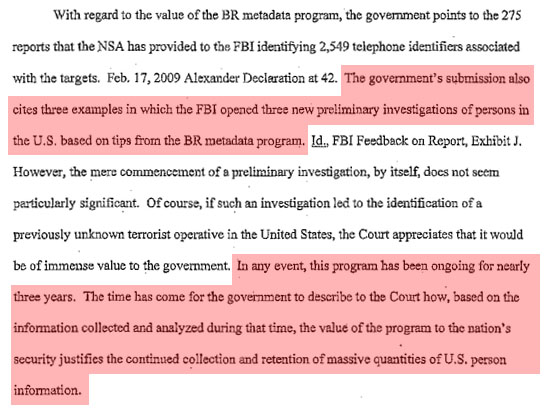

What it does: This bill takes aim at “Section 215” of the Patriot Act, which expanded the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act to justify broad phone surveillance by allowing the government to compel companies to give up “tangible things” that could be relevant to a terrorism investigation. Under this new legislation, the government has to show demonstrable facts that the information they’re scooping up is relevant to an investigation. The bill would also insert language into FISA allowing the government to collect information that pertains “only to an individual”—so millions of others couldn’t get swept up in the NSA’s phone metadata dragnet, which hoovers up information like call times, locations, and phone numbers. What the bill doesn’t do is revise the 2008 amendments to FISA, which provide the legal basis for programs like the NSA’s PRISM—the main NSA program that vacuums up online communications. Finally, the bill mandates that the inspectors general for the Department of Justice and “each element of the intelligence community” investigate how many Americans have been targeted by requests made under FISA and how their information has been used.

A Bill To Modify the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (S. 1182)

Sponsor(s): Sens. Mark Udall (D-Co.) and Wyden, Ron (D-Ore.)

What it does: Like the LIBERT-E Act, this legislation narrows the amount of information the government can collect when conducting a terrorism investigation under the Patriot Act, and how many people can be targeted. It would require the government to produce a “statement of facts” showing there are “reasonable grounds to believe” that the records being collected are relevant to an investigation and “pertain to an individual in contact with, or known to, a suspected agent of a foreign power.” Unlike the LIBERT-E Act, this bill lacks the word “only,” which could give the government more wiggle room.

The FISA Accountability and Privacy Protection Act of 2013 (S. 1215)

Sponsor(s): Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.)

What it does: The bill attempts to shed more light on the NSA’s spying program by requiring government watchdogs to audit national security letters and other top-secret orders; the Attorney General to submit reports to major congressional committees every six months detailing the number of secret national security requests that have been made relating to US citizens; and the government to release to the public an annual report on how FISA is being used and impacting the privacy of Americans. The legislation also reforms the controversial Section 215 of the Patriot Act with similar language to Udall and Wyden’s bill.

The Surveillance Transparency Act of 2013 (S. 1452)

Sponsor: Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.)

What it does: One of the biggest complaints by tech giants including Google and Facebook is that they are forbidden from telling their users when they are forced to give up user data. This bill would require the government to provide annual public reports on the total number of orders granted under FISA and the Patriot Act, how many users were targeted, and the number of times the government queried “certain databases under specified orders.” The bill would also allow tech companies to disclose information about the number of orders they receive that approve “electronic surveillance, pen register and trap and trace devices, the production of tangible things (commonly referred to as business records, including books, records, papers, documents, and other items), and the targeting of persons outside the United States other than US persons.”

Government Surveillance Transparency Act of 2013 (H.R. 2736)

Sponsors: Rep. Rick Larsen (D-Wash.) and Justin Amash (R-Mich.)

What it does: This bill would also give tech companies more leeway in what they can tell their users by allowing them to report aggregate information related to orders they receive under FISA every 3 months.

The FISA Judge Selection Reform Act of 2013 (S. 1460) and the FISA Court Reform Act of 2013 (S. 1467)

Sponsor: Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.)

What they do: The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which approves surveillance requests has been criticized as a “rubber stamp“; these bills seek to change the way judges are selected and bring more accountability to this secret body. S. 1460 would revamp the nomination process for surveillance court judges, who are currently appointed by the chief justice of the Supreme Court with no congressional oversight. Under this legislation, each federal circuit would nominate a judge to the court, which the chief justice would then have to pick from; it would also add two new judges to the court. S. 1467 would further reform FISC by establishing an office that has the power to declassify rulings and appeal the court’s orders, potentially all the way up to the Supreme Court.

FISA Court Accountability Act (H.R. 2586)

Sponsor: Rep. Steve Cohen (D-Tenn.)

What does it does: The bill would take most of the responsibility for appointing surveillance court judges away from the chief justice of the Supreme Court, placing it in the hands of the majority and minority leaders of the House and Senate.

Presidential Appointment of FISA Court Judges Act (H.R. 2761)

Sponsor: Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.)

What it does: This bill also takes the appointment of FISA judges out of the hands of the chief justice. It would give the president the power to nominate judges to this court, who would undergo the typical Senate confirmation process.

The Ending Secret Law Act (H.R. 2475)

Sponsor: Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Calif.)

What it does: It requires the surveillance court to declassify all of its decisions and orders that include “significant legal interpretation” within 45 days. But there’s a big exception—when the Attorney General determines that “disclosure is not in the national security interest of the United States and for other purposes” the court only has to release an unclassified summary of the decision.

House Resolution No. 205

Sponsor: State Rep. Tom McMillin (R-Mich.)

What it does: This resolution has one purpose—ousting NSA Director James Clapper. It reads: “We urge the Congress of the United States and the U.S. Attorney General to prosecute Director of National Intelligence James Clapper for lying to Congress about the National Security Agency’s collection of data on U.S. citizens…Effective congressional and public oversight cannot occur if the information presented to Congress cannot be trusted.”