House financial services committee chair Jeb Hensarling (R-Tex.).Pete Marovich/ZUMAPress

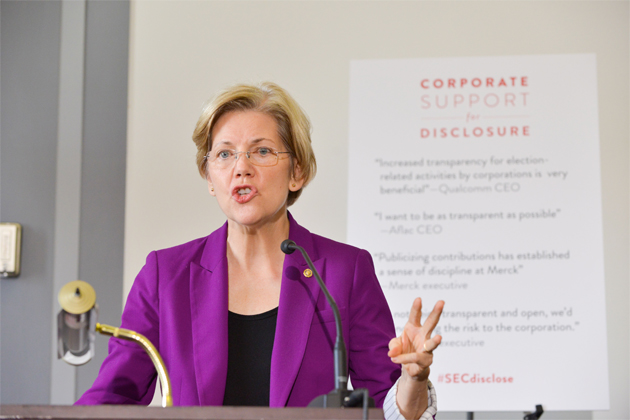

Last week, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) warned that, five years after the financial crisis, the biggest Wall Street banks are still so large and loosely regulated that their failure would endanger the entire financial system, forcing the government to bail them out. This problem—called too-big-to-fail—is worse now than it was in 2007, Warren said, because the four largest banks are 30 percent bigger than they were before the financial crisis. House Republicans have made common cause with Warren on the issue—at least rhetorically. But when it comes to proposing a solution, GOPers in the House are MIA; in fact, they’ve pushed bills that would preserve bank bailouts.

Since Republicans took over the House in 2010, the House financial services committee has held six hearings on how the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform act may not have ended too-big-to-fail.

In March, Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas), the chairman of the committee, told the Wall Street Journal that he would doggedly work to prevent more big bank bailouts. The article was titled “Texan’s Plans Put Wall Street on Edge.”

But Hensarling and his fellow Republicans have yet to propose a fix. “They’ve been in power for three years now,” says one Democratic aide. “What have they done?”

Financial reformers agree with Warren and Hensarling that Dodd-Frank has not ended too-big-to-fail. One reason is that big banks operate internationally, which limits the government’s capacity to wind down failing institutions. Another is that the rules that regulators have drawn up to implement the Dodd-Frank law are too weak, reformers say. The financial reform law says that banks have to hold onto a sufficient amount of emergency reserves to protect themselves in case of another downturn, but advocates charge that bank regulators have proposed reserve levels that are too low to save banks in case the economy tanks again.

The Democrat-controlled Senate has proposed several solutions to the problem, including requiring large financial institutions to have an emergency reserve cushion about five times current levels; restricting the government safety net to traditional banking operations such as savings and loans, rather than riskier investment banking activities; and splitting big banks’ commercial operations off from their investment activities, which would shrink the size of future bailouts.

The GOP-controlled House, meanwhile, has passed legislation making it more likely that failing banks will get government handouts, and attempted to defund measures that would help the government wind down failing banks.

In March, Hensarling told the Journal that “we have to do a better job…fire-walling” between banks’ commercial activities and their risky trading activities, so that taxpayers don’t have to bailout bank bad behavior. About a month later, though, he pushed a bill through the financial services committee that would do the opposite; it would increase the types of risky trading activities that taxpayers are on the hook for if there is another downturn. As Mother Jones reported, that bill was written by Citigroup lobbyists. It passed the full House last month.

“If you’re going to say this on the cover of the Wall Street Journal, and then do the bidding of Citibank…do you really mean [you want to end too-big-to-fail]?” says Marcus Stanley, policy director at the advocacy group Americans for Financial Reform.

A spokesperson for the House financial services committee did not respond to requests for comment.

House Republicans have proposed other measures that would make it more likely for banks to get a government bailout. Earlier this year, the House financial services committee advised House budget makers that lawmakers could save taxpayers billions by repealing the section of Dodd-Frank that gives the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) the ability to wind down failing banks so their collapse doesn’t wreak havoc on the broader economy and necessitate a bailout. (The measure would not result in savings.) Paul Ryan’s 2013 budget attempted to repeal this provision too.

Why the disconnect between House GOP rhetoric and reality? Because taking on the banks is hard, Stanley says. “You can use the buzzwords of too-big-to-fail, and you can talk about disliking bailouts and whatever,” he says. “But as soon as you start to get into actually proposing ways to reduce the dependence of big banks [on government]…you’re taking on some big financial interests. That’s a lot harder thing to do.” (He adds that it’s not just Republicans who get nervous going up against the banks.)

Jeff Connaughton, a former investment banker and author of The Payoff: Why Wall Street Always Wins, says that House Republicans are simply “in the tank for Wall Street.” The financial sector has given 66 percent more money to Republicans than to Democrats over the current election cycle.