Anikei/Thinkstock

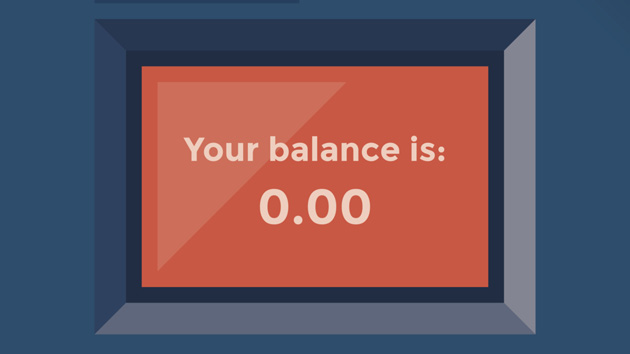

It’s expensive to be poor. A new report out from the California Reinvestment Coalition concludes that the big banks are charging some of California’s poorest families hefty ATM fees to access monthly benefits from the state welfare program known as CalWORKs, skimming at least $19 million a year, the group estimates, from this taxpayer-funded program.

The average CalWORKs family is an adult with two children who gets $510 a month worth of benefits, or about $6,120 a year. That’s not enough to live on, not even close, and the benefits are 8 percent lower now than they were in 2011. On top of that, accessing the funds costs them as much as $4 per ATM transaction, fees they really don’t have any alternative but to pay. That’s because California doesn’t ask its vendors to do much by way of accommodating the recipients. A $69 million contract with Xerox to administer an electronic benefit transfer card system has helped make these EBT cards the default way to deliver public assistance, and there’s no state requirement that banks waive ATM fees for people who use them.

In a press release, Andrea Luquetta, author of the report, explained:

For families trying to escape poverty, these fees siphon away money that could be used for school supplies, transportation or medicine. The current system leads too many people to pay fees just to access the very benefits they need to survive. It is a diversion of taxpayer dollars away from their intended use of supporting families. That’s why we’re calling on the state, banks, county offices, and nonprofit partners to work together to address this pressing issue.

The average EBT user pays about $5 a month in fees, but Luquetta says that figure masks the real story, as some people successfully avoid paying the fees while others pay a lot more. “It is typical for someone to pay the fee at least twice in a month in order to withdraw all of the cash in as few transactions as possible. At a Bank of America ATM that will cost $6. And then, of course, there is the challenge of what to do with that cash—load it onto a prepaid card? Buy money orders? All of that costs fees as well that we don’t capture. I even know a few people who pay the fee at a Bank of America or Wells Fargo ATM and then turn around and deposit the cash into their account at the same bank,” she said in an email.

In theory, someone receiving CalWORKs benefits could have the money deposited directly into a checking account for free. In fact, most of the beneficiaries don’t have checking accounts, largely because they can’t afford them. More than 96 percent of beneficiaries use the EBT cards. Many welfare recipients are leery of bank accounts, having previously suffered high overdraft fees and other fees charged by banks.

Some of the banks benefiting from the EBT fees have helped play a role in stoking those fears of traditional banking. The largest beneficiary by far of EBT-related ATM fees in California is Bank of America, which hosted 12 percent of the transactions in 2012, earning $3.6 million, according to the coalition. Back in 2004, a California jury hit the bank with a verdict that would have potentially exposed it to $1.2 billion in damages in a class action lawsuit filed by Social Security recipients who’d had their federal retirement or disability benefits seized directly from their accounts to pay excessive overdraft fees—a practice that left many low-income seniors and disabled people in dire straits. Plaintiffs showed that, like many banks at the time, BofA processed checks in a way that often made more of them bounce, thus increasing the fees it could automatically deduct. (A BofA spokeswoman says the bank no longer processes checks that way.)

The Obama administration came to BofA’s defense in the case, which went all the way to the California Supreme Court; the verdict was overturned on appeal. But publicity around the case went a long way in exposing the sorts of problems low-income people encounter when they do business with big banks. Given this history, it’s hard to blame families for not wanting to entrust these institutions with their meager benefit checks. But the banks have figured a way to make them pay anyway.