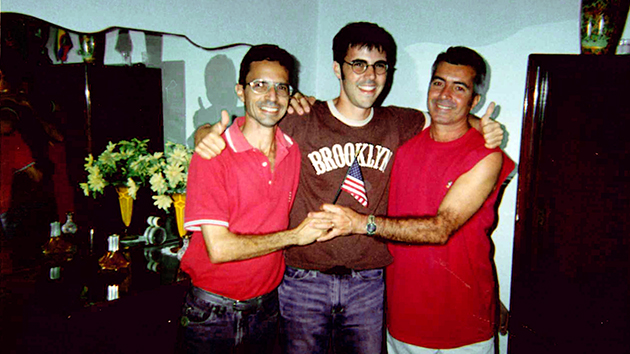

Carlos (left) and Luis Enrique (right) with the author, 2005. (The flag was their idea.)

When Luis Enrique passed in early September, just a couple of months after first learning he was HIV-positive, Carlos took his remains to Cuba’s best funeral parlor, the one where they bring the government officials. He had seven of the nicest wreaths made, and he dressed Luis Enrique, his longtime partner, in his best clothes. Their Italian friend Maurizio had once given them some French cologne, and Carlos made sure to spritz it throughout the coffin. He then rode with Luis Enrique by the church before ending up at the cemetery, where another friend gave a stirring eulogy. Carlos dabbed some more cologne in the tomb and headed home.

He told me all of this in an email, two weeks later. He was wiped out. “Don’t stop writing me,” he said, “since the emails make me feel like I’m surrounded by people I care about.”

As it turns out, Carlos was HIV-positive too.

We first met Carlos and Luis Enrique at the doorstep of their apartment during a blackout, deep inside a tumbledown building off a dilapidated thoroughfare in Central Havana. Large chips of paint had fallen from the facade, and the dark, humid stairwell reeked of fresh dog shit. It wasn’t exactly where my wife and I had envisioned staying at the start of our two-week Cuban vacation.

It was 2005. We were living in Venezuela at the time, and after reading an article online about a Cuban tax on exchanging US dollars, I was convinced that we should bring bolivares instead. Chávez and Castro were panas, right? Perhaps, but upon arriving at José Martí International Airport we learned the limits of that friendship: There was virtually nowhere to exchange Venezuelan currency on the entire island.

A cabbie brought us into the city after we’d explained our situation. He assured us that the two men now in front of us were good people, that their unregistered casa particular was the most affordable place to stay. Brooke and I shared a glance—as if to say, We’ve stayed in dodgier-seeming places before, right?—and steeled ourselves for the introduction. Carlos, whose threadbare tank top hung low off his slight frame, asked us where we were from. Brooke smiled. “The United States.” Walking to his tiny kitchen to prepare coffee, Carlos stopped short. He turned around and folded his arms across his chest. While Luis Enrique, the graying one, whispered Estados Unidos behind me, Carlos took a step back, as if he were trying to get a better look at the two of us. They’d never met Americans before.

After a pause, Carlos snapped back to life. He let out a big smile, unfurled his arms, and pointed above the doorway to the dining room. There, a mid-’80s Madonna poster looked down on us, her hair short-cropped, her bejeweled bra exposed. “Imagine that, Luisito,” said Carlos, still grinning. “Americans!”

The lights were out, they told us, to save electricity for the Canadian and European tourists who would crowd Old Havana’s colonial plazas and Varadero’s white-sand beaches that summer. We sat in the dimming apartment, sharing stories. When they found out we’d lived in New York, they pumped us full of questions about everything from the state of the World Trade Center site to the length of a subway car. After the lights popped back on Carlos shared his music collection—a hodgepodge of Madonna, Michael Jackson and, strangely, Barry Manilow—while Luis Enrique prepared a dinner of rice and beans.

While we ate they told us that they each earned roughly $10 a month as a bookkeeper (Carlos) and grocer (Luis Enrique). They had met years ago, after Luis Enrique arrived from the central countryside; it was his idea to rent out a bedroom in Carlos’ place to make a little extra money. We were their third guests halfway through 2005. Because they didn’t have a license from the government, which cost about $150 monthly, they were a strictly word-of-mouth operation.

After several hours of conversation, we felt comfortable enough to tell them that we only had enough cash for a day, and that we would be searching for a place to change our bolivares the next morning. When Luis Enrique got the gist of what we were saying—that these young Americans didn’t bring the world’s most recognizable currency along with them—he shook his head and cringed. “You messed up,” he said.

We were in some kind of trouble. Because of the embargo, we couldn’t use our credit cards to get a cash advance or buy new tickets home. Since we didn’t want to risk possible State Department fines, going to the proto-US Embassy known as the Interests Section was out. By trying to save a couple hundred bucks on the dollar tax, we’d ended up having to try to survive on about $20 for two whole weeks.

Carlos must have noticed the stress on my face. He walked past the refrigerator, a 1940s Westinghouse beauty, and over to a couple of buckets. “Don’t worry,” he said, opening the lids. “We have rice. We have beans. We have eggs. Forget the money. Están en su casa.”

The next two weeks were a whirlwind. Within a few days, we figured out the money situation, thanks to Western Union and our incredulous but accommodating families. Because we were having such a good time with Carlos and Luis Enrique, we scrapped our plans to try to travel across the entire island and stayed closer to Havana to spend more time with them, off the tourist circuit. So instead of checking out cigars in Pinar del Río, for example, we ended up a party at Carlos’ workplace, a meatpacking plant, where folks drank Bucanero by the crate and a British grad student named Camillia sang Dido karaoke to an entranced crowd.

We passed hours around their dining room table, drinking nips of rum and talking about practically everything. (Things we didn’t discuss: the contours and complications of their relationship, and Cuba’s historical persecution of gay men.) Both Carlos and Luis Enrique were around 40 and never had known life without Fidel. They told us they admired his character and strength, and that they both were repulsed by the idea that some day, a Miami-bred Cuban American might try to take the apartment away, claiming it was his family’s 50 years ago. That said, they loved what little American culture they could access and considered Cubans and los yumas to be brothers separated by a messy divorce.

Some of that came from their families. When Carlos was 16, his parents applied for the Interests Section lottery, which each year grants some 2,000 visas to Cubans. Somehow, Carlos parents hit the jackpot. There was only one problem: He didn’t want to go. He believed deeply in the revolution and just couldn’t see himself leaving. So, despite waiting years to leave, his parents died in Cuba. On the surface, Carlos always played by the rules, always did what the state expected. But here he was, the proprietor of an unregistered casa particular, paying off the neighborhood snitch from the Committee for the Defense of the Revolution with mayonnaise and chocolate (“Cuban business”) and guarding an armoire full of deodorant, toothpaste, and aftershave given to him by guests during the past several years.

If Carlos was nervous and overly excitable, Luis Enrique was guarded, depressed. A week into our stay he told us that he had planned to leave for the United States during a paid-for trip to visit friends in Bogotá. His nephew in Naples, Florida, had fronted $6,000 and set it up: Luis Enrique was to go to Caracas, where we would get a fake Venezuelan passport, and fly to Mexico City, after which he would make his way to the Texas border. His nephew would meet him there, and upon crossing he would qualify for asylum. Two months into the stay in Bogotá, he crossed into western Venezuela and made his way to the capital. He was terribly nervous at the airport, and when he got to immigration he handed over the passport. The agent looked at it, then at him. “Sir, you and I both know this is fake.” Luis Enrique tried his best Venezuelan accent. “Sir, you should just turn around and walk away.” He did.

Looking back, Luis Enrique wondered if he should’ve stayed in South America, as his nephew had wanted. He had sold everything he owned, and he moved in with Carlos, he said, to avoid his empty apartment. When he told us the story, he seemed resigned to the fact that he’d be in Cuba until Castro’s death, maybe longer. “I’m scared,” he told us. “Who knows what the United States will do? I think there will be a lot of people who will try to humiliate us Cubans. I’m not looking forward to that.”

Carlos’ emails often started by lamenting the fact that he hadn’t heard from us in months. “HAVE OUR AMERICANITOS FORGOTTEN US?” But when he wrote to tell us that Luis Enrique was sick, he was sober and to the point: “I haven’t been able to write because the news here is pretty sad.” He’d later send photos from the hospital, with an exhausted-looking Luis Enrique underneath a purple-and-green blanket, Carlos standing by his side, in scrubs.

Last week, I wrote to Carlos to see how he was holding up, a couple of months after Luis Enrique’s death and a couple of months after he’d started his own HIV treatment. I didn’t think much of it when I didn’t hear back right away, given his condition and the generally unreliable internet connection on the island. And then, early Wednesday morning, I got this response:

Subject: MESSAGE

HELLO, CARLITOS DIED OF HIV TOO AFTER LUISITO. THIS A FRIEND OF THEIRS, LA MULATA WHO LIVES AROUND THE CORNER WHO RENTS TO FOREIGNERS. THIS IS MY EMAIL ADDRESS NOW. IF YOU EVER COME TO CUBA AND NEED A ROOM…

No warning, no slow decline, no goodbye. He was gone too, just like that—and just before the Obama administration made history by reestablishing diplomatic relations between the United States and Cuba.

I’ve spent a fair amount of time thinking about Carlitos and Luisito these past few months, flipping through photos and replaying those two weeks over and again in my mind, and I keep coming back to the last night Brooke and I spent with them. It was a Saturday, and we arrived back at the apartment from a stroll along the Malecón at midnight, mid-blackout. Central Havana was dark—even the normally bright Capitolio was unlit—but inside Carlos’ building his neighbors milled around, tense. The illegal-cable guy was on the roof.

They had been waiting for weeks, although no one knew what to expect. There allegedly were two American channels available for $10 per month. Carlos wanted to watch American music videos. Luis Enrique wanted Hollywood movies. The taxi dispatcher next door wanted Major League Baseball, while his wife, whom everyone called China, wanted Mexican soaps. The wannabe rocker upstairs said he didn’t care, but he was getting cable anyway. Everybody was.

The outage didn’t last long. Gustavo, the cable guy, went to work when the oscillating fans puttered on, barking orders to the roof through a walkie-talkie. He almost looked like a professional. His silver Motorola cellphone hung from a belt clip off olive Abercrombie cargo shorts, covered at the belt by a ribbed white tank top, and in the new light I could see he was covered in sweat. Carlitos paced in front of his red wicker-and-vinyl couch, long ago warped by the humidity, and asked Gustavo several times if he could help. Brooke laughed and told Carlitos to relax, and Luisito stood with China outside, waiting for the first program to come across the screen.

The whole process took no more than 20 minutes. Soon Gustavo gave the word, and his partner clicked into the movie. We stared at the television, dying to see what the first yanqui transmission in the building’s revolutionary history would be. I hoped for something classic, maybe even artistic. Instead, we got the Wayans brothers spoof Don’t Be a Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood. Brooke shook her head and sighed. The Cubans were transfixed.

The clock read 1:45 a.m., and it looked like they would be up all night watching whatever beamed though the screen. When I woke up and padded across the cool marble into the living room early that morning, Luis Enrique was sitting in the very same spot on the couch, watching Bob the Builder in Spanish. He hadn’t slept much, but he grinned at me from beneath Madonna’s pouty lips. “You know, Carlos is the most communist person in the building,” he said, leaning in, “and even he has cable now.”