James Robinson/Horace Cort/AP Photo

It started slowly. A few people began banging spoons against the metal pillars. More joined in, hitting them against benches. The people sitting down started too, slamming their spoons against the concrete floor. Soon, the deafening clamor of hundreds of synchronized spoons was sounding across the Montgomery BART station in downtown San Francisco. They were tapping a message: The movement is still alive.

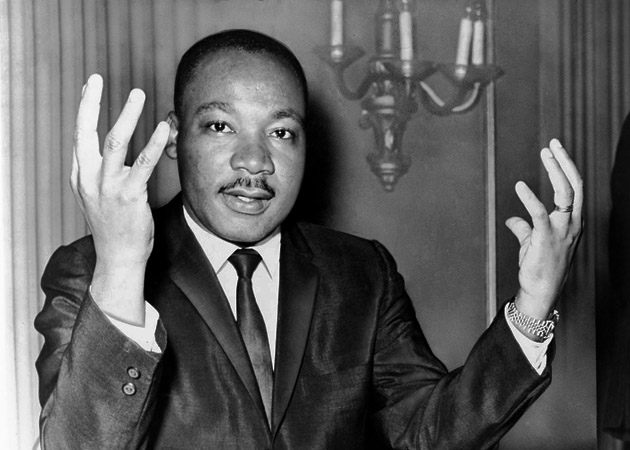

Sixty years after Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech about the Montgomery bus boycott—the speech that helped set off the Civil Rights Movement—hundreds of activists gathered at the station early Friday morning to protest in his spirit. It was the first of many demonstrations scheduled around the country this weekend—an attempt to “reclaim King’s Legacy.” People filled the light-rail platforms, shutting down two stations that service the city’s downtown financial district. “BART FRIDAY: NO BUSINESS AS USUAL” proclaimed the all caps header on the event’s Facebook page.

The protesters’ demands were specific, but their point was broader. “Part of what we are trying to do over the next 96 hours is remind people that Martin Luther King believed in direct action. He was not the pacified image they teach in classrooms,” said one organizer, barely audible over the spoons.

Clayborne Carson, a historian and director of the Martin Luther King Jr., Research & Education Institute at Stanford University, concurs. “One puts King back into the past and it is more of a comforting notion of King,” he says. “One of the messages you get at a King holiday celebration is, ‘We had this problem called racism once, and he helped us solve it.’ There is this comforting notion that King was part of a past that America has moved beyond and we can all pat ourselves on the back.”

Though Carson emphasizes that discussing and celebrating King’s legacy is an important and positive aspect of the holiday, it doesn’t give the full picture. “There are those who are going to say the meaning of his life is that he helped America pass Civil Rights Legislation. We should be looking beyond that.” Even during his life, Carson explains, King was not satisfied with legislation as an end result. He hoped civil rights would be a catalyst for the realization of international human rights and justice. “King’s last book was, Where Do We Go From Here? He wouldn’t be asking if we had already arrived.”

The Civil Rights Movement of the ’50s and ’60s marked an important turning point in American history. But members of Black Lives Matter, as the fledgling movement is often referred to, hope to highlight that there’s still much to be done—that the battle for equality is just beginning.

The movement began to take shape in August, after a grand jury declined to indict Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson for killing unarmed teenager Mike Brown, kicking off weeks of demonstrations. It may have been a local incident, but it represented a national problem: There were Mike Browns in every community and plenty of people were fed up.

Protests erupted around the country, mostly in towns where tensions had long been brewing. Anger turned to action as people took to the streets to remind America that racism wasn’t merely something from the past. It lived in people’s day-to-day experiences, in our growing economic inequality, and, most visibly, in the criminal justice system. As my colleague Jaeah Lee reported in August, African American men are disproportionately the victims of police aggression.

“We need not look for individual racists to say that we have a culture of policing that is really rubbing salt into longstanding racial wounds,” NAACP president Cornell Williams Brooks told Mother Jones. It’s a culture in which people suspected of minor crimes are met with “overwhelmingly major, often lethal, use of force.”

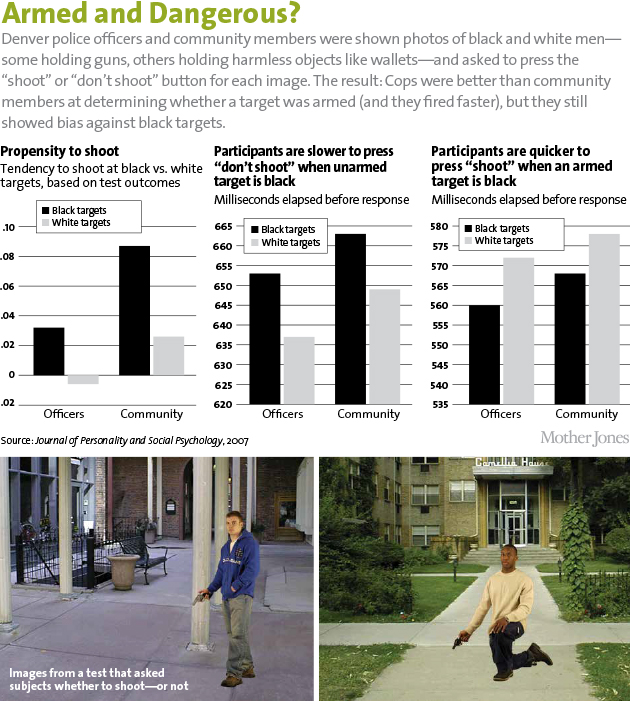

Studies also reveal that racism has etched itself into our collective subconscious. Chris Mooney’s deep-dive into the research shows “that racially biased messages from the culture around you have shaped the very wiring of your brain…

An impressive body of psychological research suggests that the men who killed Brown and Martin need not have been conscious, overt racists to do what they did (though they may have been). The same goes for the crowds that flock to support the shooter each time these tragedies become public, or the birthers whose racially tinged conspiracy theories paint President Obama as a usurper. These people who voice mind-boggling opinions while swearing they’re not racist at all—they make sense to science, because the paradigm for understanding prejudice has evolved. There “doesn’t need to be intent, doesn’t need to be desire; there could even be desire in the opposite direction,” explains University of Virginia psychologist Brian Nosek. […] “But biased results can still occur.”

So, MLK Jr.’s question remains: Where do we go from here?

Manuel Pastor, a professor of sociology and American studies at the University of Southern California, leads a team of researchers who seek to understand how movements develop and have an impact. He says that for these protests to open the race conversation on a wider scale and become a true movement—rather than just a moment—certain strategies are critical: “A movement needs to have a grassroots space. It needs to have a broad vision of what might change, a pragmatic policy package announcing things that actually could make a difference, what could be done. It needs to have sort of a theory of what the government might do. It needs to be intersectional, connecting different strands of arguments and strands of movements so it can become a bit bigger than a single issue or a silo.”

So far, most organizing efforts have been at the local level. The particulars in Oakland are not the same as those in New York. Ferguson has its own priorities and strategies, as does Los Angeles. But Pastor says local actions are where people can begin to have an impact: “What we are seeing with Black Lives Matter is a combination of highly localized issues. And there is no shortage of police community tension around the country that people can be part of. So people have local handles but they are really seen as part of a broader national challenge.”

Indeed, the local protests already have had national impacts. A new Gallup poll reveals that Americans are more concerned about racism than at any time since the Rodney King beating in Los Angeles. State legislatures across the country have filed scores of bills to put more scrutiny on police interactions with the public. As a direct response to Ferguson, the Obama administration announced the creation of a task force to study the problem and recommend solutions.

But if it’s going to make a difference, the movement needs to figure out how to keep its momentum and public interest over the long term. “If you think about a movement that fell flat on its face but captured the imagination of the nation dramatically, it is Occupy,” Pastor says. At the outset Occupy raised the issue of inequality “so successfully that very few people were able to push back. In fact, when Mitt Romney talked about the 47 percent of people who were ‘takers’, it just rankled people because that ground was primed by the work of Occupy.” But Occupy was too decentralized and nonhierarchical to last: “You don’t win without organization,” Pastor says.

In many areas (notably Oakland, L.A. an New York City), the Occupy networks have continued to play a role. The Black Lives marches have used Occupy tactics and utilized the same communications platforms. Like Occupy, Black Lives currently has no hierarchy or visionary leader as the face of the movement. Factions develop, disagreements happen at demonstrations, and already the movement has had to resolve how to include people who have not been victims of racism but who feel passionately about the issue—without allowing them to co-opt it.

Yet Black Lives is distinct from Occupy both in its focus and what its members aim to achieve. To succeed, it needs leaders who can distill the protesters’ sentiments into specific policy recommendations while establishing a collective narrative—something that gets at the big picture without losing sight of what’s happening in local communities. And that’s beginning to form. This week, organizers launched WeTheProtestors.org, an online hub for supporters and activists.

DeRay McKesson, one of the website’s creators, has been involved in the protests since Ferguson, and has traveled to seven cities, working to organize the movement. He and his partner Johnetta “Netta” Elzie, started with a newsletter in September and have become known entities on Twitter, spreading information and support. “We didn’t necessarily know that the protest would spread like this,” McKesson says. “We knew what was happening in St. Louis [County] was wrong and that we needed to confront the system. What people quickly realized was that Ferguson is really two steps from their doorstep. What is happening is not coincidental—it is structural and systemic.”

He acknowledges the movement’s growing pains. “I think that what’s happening is a new form—a decentralized space with many people leading. We are all growing and learning. So how do we link everybody up in a way that is meaningful, and a way that is about the work? We are now figuring out how to do that.”

Before they can influence policymakers, McKesson says, “there has to be a community to actually leverage.” The website includes policy briefs, activist tool kits, and importantly, a list of demands, namely accountability for officials in the death of Michael Brown, and in any use of deadly force by police, and the appointment of a special prosecutor in such incidents. In short, McKesson et al. are building the tools Manuel Pastor told me are necessary for a movement to thrive.

McKesson emphasizes that the movement goes beyond the issue of policing: “Police brutality sits in concert with so many other issues. It sits in concert with housing. Police target low-income communities that were intentionally made to be the way they are. I think we have an opportunity, in the long term, to talk about those things.”

“I think that we can win,” he adds, resolutely. “But how we think about the win is really important. Being alive is a win, but it is not enough. Good schools are a win, but they are not enough. Housing is a win, but it is not enough. That matters. That way of imagining a better world as a series of wins that leads to the end of racism—that’s what will be transformative.”