The day before Halloween, a band of 40 or so middle-aged Democratic activists gathered in the parking lot of a long-closed KFC in Eagan, a southern suburb of the Twin Cities, to listen to a handful of state party leaders speak. The party bigwigs, who were crisscrossing the state on a last-minute campaign tour, crowded a small, elevated stage in front of a bright blue bus bearing a logo proclaiming it was “On the Road to a Better Minnesota.” Sen. Al Franken’s daughter Thomasin told cute tales of her dad’s pride in becoming a grandfather. St. Paul Mayor Chris Coleman—tall, crisp-suited, with a stern jaw, he could have easily passed as an extra on House of Cards—delivered the same polished anecdotes about paddling northern Minnesota’s Boundary Waters with Franken that he told at every stop.

Finally came the headliner: Gov. Mark Dayton. Engulfed in a puffy green jacket, his thinning gray hair combed over just so, Dayton stumbled through a disjointed speech. When the microphone briefly lost power, he cracked a lame joke: “This is actually secretly a DFL fundraiser, err, errr,” he said, using the initials for the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, Minnesota’s homegrown Democratic outfit. “They’re so broke they can’t even afford electricity.” He got some pity laughter. Then he embarked on an extended metaphor comparing his governorship to his days as a hockey goalie in college. “A goalie can prevent bad things from happening. But he can’t—well, at least I could never score a goal,” Dayton said, sheepishness creeping into his voice. “A couple of the pros can shoot at an empty net, but that’s another story—yeah, you know, goalies can’t win games and they can’t make things happen that way.”

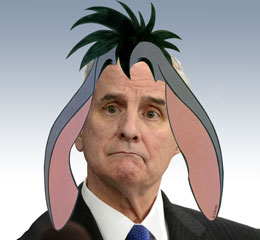

For a man who has won a competitive US Senate race and secured his second term as governor in November, Mark Dayton is a terrible retail politician. “He’s very shy and he’s an introvert,” Ken Martin, the chair of the state party and a friend of Dayton’s, told me unprompted earlier this month. “He’s not a typical, backslapping politician,” Martin continued. “He’s not very articulate; he’s kind of jerky,” Tom Bakk, the Democratic Senate majority leader, says of his ally’s style. When Dayton first ran for his current job, in 2010, The New Republic dubbed him “Eeyore for Governor.”

An heir to the Target retail fortune, Dayton, 68, has plowed tens of millions of his own money into his campaigns, but it still hasn’t come easy. He swallows his words in a rush, speaking in almost-unintelligible mumbles and frequently losing track of his point as he rambles on unrelated tangents. “He’s not a terribly articulate guy,” says Larry Jacobs, chair of the University of Minnesota’s public policy school. “He’s not a smooth talker; he struggles to give a smooth public speech.” At public events, Dayton hunches his shoulders, which makes him appear shorter than his 5-foot-10 frame, and often appears to be trying to disappear into the crowd. No one wonders whether he’ll seek national office someday. He’s not the leader of the free world—he’s your dad, struggling to make small talk with you and your friends after you get home from school.

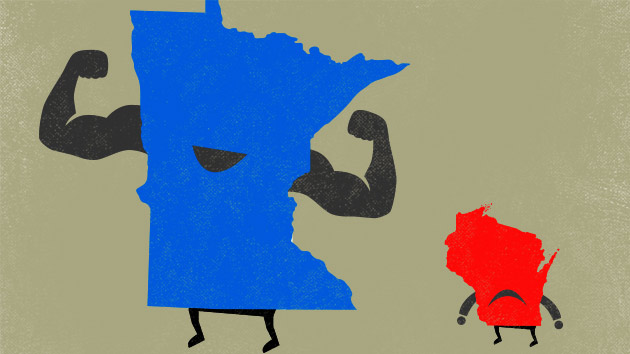

Think of Dayton as Scott Walker’s mirror image. With the help of GOP-controlled legislatures, Walker and other Republican governors, such as Kansas’ Sam Brownback, have passed wish lists of conservative policies and touted their states as laboratories that demonstrate the benefits of conservative governance. Walker, the governor of Wisconsin, has parlayed that hype into a potential 2016 presidential run. And across the border in Minnesota, Dayton seized a brief moment of unified Democratic control to create the liberal alternative to Walker’s Wisconsin—a blue-state laboratory for demonstrating the potential of liberal policies. Dayton didn’t “set out” with the objective of one-upping Walker in mind, he told me after the Eagan event. But “the contrast,” he notes, is obvious.

Over the past several years, Minnesota has become a testing ground for a litany of policies Democrats hope to enact nationally: legalizing same-sex marriage, making it easier to vote, boosting primary education spending, instituting all-day kindergarten, expanding unionization, freezing college tuition, increasing the minimum wage, and passing new laws requiring equal pay for women. To pay for it all, Dayton pushed a sharp increase on taxes for the top 2 percent—one of the largest hikes in state history. Republicans went berserk, warning that businesses would flee the state and take jobs with them.

The disaster Dayton’s GOP rivals predicted never happened. Two years after the tax hike, Minnesota’s economy is booming. The state added 172,000 jobs during Dayton’s first four years in office. Its 3.6 percent unemployment rate is among the lowest in the country (Wisconsin’s is 5.2 percent), and the Twin Cities have the lowest unemployment rate of any major metropolitan area. Under Dayton, Minnesota has consistently been in the top tier of states for GDP growth. Median incomes are $8,000 higher than the national average. In 2014, Minnesota led the nation in economic confidence, according to Gallup.

Minnesota has even pulled ahead of Walker’s Wisconsin, leapfrogging its neighbor to the east on measure after measure. “In a whole number of ways, we’re very, very similar,” Bakk, the DFL Senate leader, says of the two states. “But politically, we have taken just totally different paths in the road.”

Dayton cruised to a 5-point win in 2014, spending just $3 million in a race that received scant national attention. All Minnesota’s governor had to do was point to his policy successes. “We’ve confounded those who said if you’re going to raise taxes on the richest people they’re all going to leave the state, and all the businesses are going to leave the state and we’ll have this enormous drain on jobs. That hasn’t happened,” Dayton told me in October.

“I feel affirmed in my political views,” he says now, “and that the direction we’ve taken in Minnesota is much better for our state and for most of the people in Minnesota than what’s happened in Wisconsin. The numbers show that unmistakably…I still think they’re the right politics for the Democratic Party—and the right policies for our country.”

Before his time as governor, Dayton was largely seen as a lovable but aimless rich boy who had tried and failed to succeed in politics. In his 30s and 40s, Dayton spent millions of dollars of his own money losing two statewide campaigns—a Senate race and a gubernatorial primary. When he finally won a Senate seat, in 2000, he served a spectacularly unsuccessful single term before declining to run for reelection. “He’s a nice guy, but he’s a trustafarian,” says Stan Hubbard, a billionaire media mogul and prominent funder of GOP causes in Minnesota.

Dayton’s money comes from his family. His great-grandfather George Dayton founded a department store named after the family in 1902. George Dayton’s heirs built the nation’s first fully enclosed mall in Edina in 1956. In 1962, the family branched out, opening the first Target in Roseville, Minnesota. A Dayton’s department store anchored most Minnesota malls until 2000, when the Dayton-Hudson Corporation became Target Corporation.

The Target wealth—the family fortune is estimated at $1.4 billion—bankrolled Dayton’s runs for office. But that privileged upbringing also turned the millionaire heir into a devoted liberal—the sort of second-generation plutocrat who knows the inequality of the system firsthand and wants to tear it down. “To whom so much has been given, to him so much be required,” Dayton recalls as his father’s favorite Bible saying, and at first Dayton studied to be a doctor before engaging with ’60s politics in college. Dayton became a campus radical during college at Yale, and protested Honeywell’s role in making bombs for use in Vietnam even as his father sat on the company’s board. After he graduated in 1969, Dayton taught at a school on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and then transitioned to social work at Project Place, a South Boston-based organization that works with homeless young people. Dayton’s annual $30,000 donations covered a tenth of his employer’s budget. After four years in Boston, Dayton turned to politics, breaking from his Republican parents to fight for liberal causes. He worked as an aide in Minnesota Sen. Walter Mondale’s office, then moved to Atlanta to work on Mondale’s vice presidential campaign. He was an original donor to Mother Jones in the 1970s. He even managed to earn a spot as the lone Minnesotan on Nixon’s so-called “enemies list”—a fact he would cite during his early political campaigns.

In 1982, when he was 35, Dayton ran for Hubert Humphrey’s old Senate seat, then held by Republican David Durenberger. Dayton called his wealth his “original sin” and promised to close tax loopholes for corporations and the rich alike. The family business was the seventh-largest nonfood retailer in the country at that time, and Dayton sold off a large chunk of his shares to eventually throw $7 million of his own money into the campaign, which became one of the most expensive Senate races ever. But Durenberger tied his fortunes to the popular Ronald Reagan, attacked Dayton as a political novice unprepared for the job, and easily held on to his job.

After the loss, Dayton struggled with alcoholism, but got sober—he checked into the Betty Ford clinic in 1987—and reined in his ambitions. In 1991, he ran a successful campaign for state auditor, serving an unremarkable four-year term. In 1998, he lost a gubernatorial primary to Humphrey’s son Skip, but he ran for statewide office again in 2000, forgoing “an expedition to the North Pole to make his second Senate run,” according to the Philadelphia Inquirer. Dayton spent $12 million of his own money and was able to oust the incumbent, Republican Rod Grams.

But Dayton picked a terrible time to join the Senate Democratic caucus. He spent just 18 months in the majority when he was still a junior senator with little sway. With Democrats otherwise in the minority, he couldn’t pass anything of consequence and grew visibly bored with the job. “The reality, he quickly learned, is that being 100th out of 100th in terms of seniority in the US Senate is not a good place to be,” state party chair Martin says. “It was just a lot harder for him to do the types of things he wanted to do.” At first, Dayton had Paul Wellstone, a fellow liberal Minnesotan, to offer guidance and keep him company in Washington. That changed after Wellstone died in a plane crash 11 days before the 2002 election. “It really soured him on Washington and changed his perspective quite a bit,” Martin says. “It became a lot more miserable for him being out there without Paul.”

Dayton became one of just 23 senators to vote against the Iraq War, but his liberalism made it next to impossible to get anything done in the GOP-controlled Senate. Uninterested in the drudgery of legislative bickering, he came unmoored. He would later admit that he struggled with alcoholism and depression during the end of his tenure into the Senate.

In 2006, Time declared Dayton one of the five worst senators in the country, and even he couldn’t really disagree, grading his term in office an F for job performance (he did, however, give himself an A for effort). “I found my role in the Senate extremely limited…Effectiveness in the Senate is majority and seniority, and I had had neither,” Dayton told me over the phone last week.

He skipped running for reelection to spare himself the hassle of fundraising (he didn’t want to be the only person funding his campaign) and the embarrassment of a likely loss. “There will be plenty of Democrats who will say he had his chance, and he blew it,” political scientist Steven Smith decreed when Dayton left office in 2007. “They will make a credible argument that he will not make a great candidate. He came across in the eyes of many Minnesotans as a lightweight as US senator.”

But Dayton wasn’t ready to give up on politics. “I wasn’t able to make much of a difference,” in the Senate, he says, “but I was still interested in trying to make a difference.” As his Senate term wrapped up, he began laying the groundwork for a gubernatorial run. Minnesota Democrats weren’t thrilled with the idea. In the summer of 2010, party officials voted to endorse Margaret Anderson Kelliher, the speaker of the state House of Representatives. But Dayton ignored that setback and went on to defeat the largely unknown Kelliher in the August primary.

A Democrat hadn’t won the Minnesota governorship in over 20 years, and 2010 was an awful year for Democrats nationwide, as the GOP won a record number of governorships and state legislative seats. But Dayton, who ran on a soak-the-rich platform of massively hiking income taxes on the wealthiest people in the state, lucked into facing Tom Emmer, an opponent who was even more politically inept than he was, and Tom Horner, an ex-Republican turned third-party spoiler who peeled off 12 percent of the vote, mostly from moderate Republicans. Dayton won, limping into the governorship after a monthlong recount on the strength of an 8,800-vote margin.

Dayton came into office as the state GOP was fighting the final battles of a civil war that had already pulled the party dramatically to the right. For decades, the Minnesota GOP—which until 1995 had called itself the Independent-Republican party—had worked with Democrats to invest in education, infrastructure, and job growth. That began to change in the 2000s, as religious conservatives like Michelle Bachmann displaced the Rockefeller Republicans of old. The state’s last budget surplus came in 1999, when then-Gov. Jesse Ventura returned the money to voters in the form of tax cuts and rebates rather than shoring up the state budget for a rainy day. When, inevitably, revenues later dipped, Republicans under Gov. Tim Pawlenty refused to raise taxes (especially as Pawlenty began to angle for the White House). The state constitution prohibits the government from borrowing money in almost all instances, so legislators pushed costs down to the school districts that could take out loans, with the hope that the state would one day pay them back.

By the time Dayton was sworn in, on January 3, 2011, the recession and Pawlenty’s budget tomfoolery had left Minnesota with a $6.2 billion deficit for the next two years, and the state GOP, which had won control of both houses of the Legislature for the first time since the state ended nonpartisan elections in 1974, was in no mood to help. Immediately following the 2010 election, the state GOP excommunicated Republicans who had endorsed Horner, the independent, for governor—including Arne Carlson, who had been the Republican governor of the state for eight years in the 1990s. Tony Sutton, the state party chair, warned Republicans in the House and Senate that they too would be cast out if they dared to compromise with Dayton, let alone raise taxes. “It created this really nasty sort of dynamic within the Legislature where many of these Republicans felt like they were more allegiant to their party leader than to the people who voted them in,” says Ken Martin. Dayton was back where he had been in the US Senate—a lonely liberal who had made a lot of promises he couldn’t keep.

When Dayton and GOP leaders couldn’t strike a deal, the state government, starved for funding, shut down. Dayton initially dug in his heels, vetoing nine budget bills in a row. “The Republicans’ all-cuts budget is extremely harsh and unfair to thousands of Minnesotans, and it’s not Minnesota,” Dayton said at the time. “The Republicans remain intransigent. They won’t budge $1 from the position they’ve held all through the session.”

Democrats in the Legislature and outside activists felt confident that they held the upper hand as the shutdown dragged on. But three weeks into the crisis—by then the longest state government shutdown in US history—Dayton gathered party leaders in his office and surrendered. He agreed to the Republicans’ terms, and continued Pawlenty’s practice of filling budget holes with temporary borrowing chicanery. The budget gained few votes from DFL legislators, with the Democrats’ leader in the House damning it as “the most irresponsible budget in state history.” It was supposed to have been Dayton’s make-or-break moment—and it looked like he broke. “Many Democrats thought he gave up more than he should to get the state open again,” says Steven Schier, a political scientist at Carleton College.

Dayton muddled through the rest of the first half of his term, vetoing what he could. “When those Republicans arrived here in January 2011,” Dayton says, “they had their mandate and they were ready to rock and roll. Everything was coming at me. I’m a hockey goalie—it felt like a warm up where everybody was hitting the pucks at the same time. But, you know, I used 57 vetoes, so that was my ultimate recourse, just to block most of what they were trying to accomplish.”

Republicans found a workaround, bypassing Dayton’s veto to put two constitutional amendments before the voters in 2012: one to implement a voter ID law, and another to prohibit same-sex marriage. The ballot measures backfired spectacularly, fueling Democratic fundraising, organizing, and turnout. Dayton and the state party cited the shutdown and the marriage measure to paint Republicans as obstructionists and overreaching social crusaders. Two years after Dayton took office, Democrats were swept back into legislative control, (11-seat majority in the Senate, 12 seats in the House), and he finally had his chance.

“When he won, expectations were a little low,” Bakk, the Senate majority leader, says of Dayton’s 2010 win. “I hear from people on the street all the time, ‘I’m really surprised by Mark Dayton.'”

By 2013, it had been two decades since the DFL last controlled both the Legislature and the governorship, so every Democratic ally and interest group had a long wish list. But after years languishing in the minority of the US Senate and dealing with an obstinate GOP legislature, Dayton wasn’t going to let the opportunity to implement his agenda pass him by. “It was a very exciting opportunity,” Dayton says, noting that he’d tell hesitant allies that the voters had said “very decisively” said “they wanted to continue along on our DFL path.” He met regularly with progressive groups in the state to craft an agenda and devise strategies to push reluctant DFL legislators to take advantage of the window of one-party control. “He might not be as charismatic as other politicians out there, but he knows where he stands,” says Dan McGrath, head of TakeAction Minnesota, one of the progressive organizations that has worked closely with Dayton in crafting the new liberal regime. And, McGrath is more than happy to note, “he did not pay a political price for acting on his convictions.”

Priority No. 1 was raising taxes on the rich. The final tax plan—which bumped up income taxes 2 percent for couples earning $250,000 per year—made Minnesota the fifth-highest tax state in the nation. But the hike paid for an arsenal of new programs. The same day Dayton signed the tax bill, he also approved a $429 million jobs bill. “He was unswayed by the consultants in the Democratic Party who were counseling Democrats to go to the middle to avoid the tax and spend label that is put on Democrats,” says Jacobs, the University of Minnesota political scientist.

“Back when I first raised [the idea of] taxes on the richest Minnesotans in 2009,” Dayton says, “it was considered the kiss of death among even the Democratic political establishment of the country.” That might not have been the accepted wisdom, but Dayton now brags that he “won because of that issue,” and that “politically it was the right thing to do.”

When DFL legislators dragged their feet on passing a bill to allow homecare health workers to form unions, the SEIU—with Dayton’s blessing—sent workers to invade the Capitol and make their presence felt. “Many, many long nights at the Capitol, sleeping on the floor literally waiting for these to go through,” Sumer Spika, one of those homecare workers, told me. Thanks to that law, she’s now in a union bargaining for higher wages ($10 an hour without benefits is standard, she says). “There were a few arms being twisted,” she says. “But we had the support from the governor, so that really helped us.”

In the end, the Legislature passed the union bill Spika wanted. And pretty much everything else Dayton and outside liberal activists asked for. That two-year session is widely considered to be among the most active in recent memory by political observers in Minnesota.

In 2014, Democrats lost the US Senate and governor’s mansions in blue states such as Maryland and Illinois. In Minnesota, Democrats lost control of the state House, where Republicans won a 10-seat majority by flipping rural districts that had voted for Mitt Romney two years prior. But outside those conservative redoubts, Dayton and his allies won. Democrats kept control of all statewide offices. Every Democratic member of Congress won reelection, including Al Franken and Reps. Colin Peterson and Rick Nolan, who had been top Republican targets. And Dayton cruised to reelection.

Now Dayton is laying out a vision for further progressive changes. “This’ll be my last term,” he says. “I do not plan to run for anything else again. I’m 68 years old now, and I have four more years in this job and I love the freedom it gives me.” Since his second stint as governor began last month, Dayton has proposed a $6 billion transportation infrastructure bill that would fix the state’s aging highway system while beefing up public transit. He has suggested using the state’s new surplus for child care tax credits for middle-class families. And just last week, DFL legislators introduced a bill to guarantee paid sick time for workers, a cause Dayton told progressive activists he supports. “Dayton may remain the most liberal governor in the country in terms of his willingness to raise taxes and to spend,” Jacobs says.

Without the state House, most of those goals are likely on hold for the moment. Dayton isn’t likely to duplicate the legislative success of the past two years, at least until 2016, when Democrats hope to regain full control of the Legislature. That was the point, however mangled, of Dayton’s speech in Eagan back in October: He can’t do it alone. Goalies can’t win games by themselves. “I needed a DFL House, a DFL Senate in order to get our agenda forward,” he told the crowd at the KFC. Without them, “the things that you’re celebrating here today like raising the minimum wage, all-day kindergarten, and early childhood education and tuition freezes” wouldn’t have happened. After his many years stuck in the net trying to deflect slapshots, Datyon wasn’t going to waste an opportunity like that.