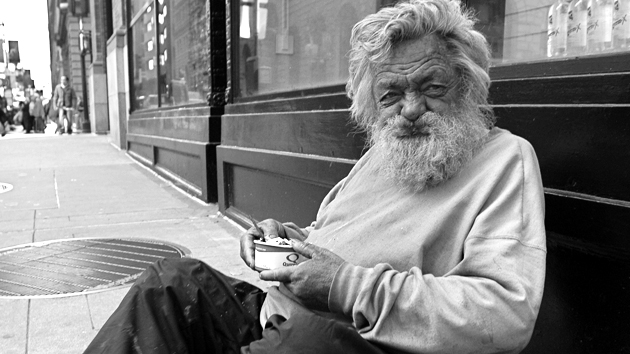

Mary "told me she had once been very beautiful, but that was a long time ago." Photographs by Robert Okin

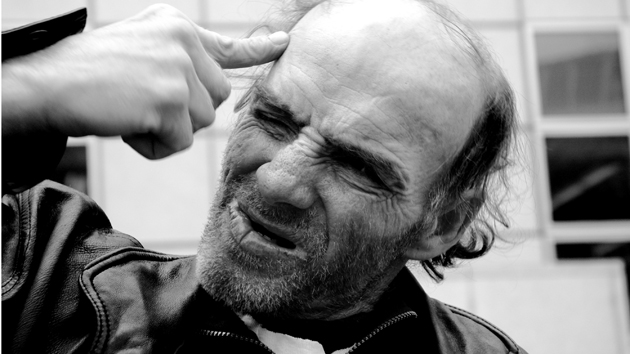

Jeff rarely smiles. After 10 years sleeping on sidewalks in San Francisco, stealing to survive and score his next heroin fix, an infection robbed him of most of his teeth. “If you have a big nose, well, no one can blame you,” he says. “It’s just the way you were born. But if you have no teeth, it’s proof that you’ve fucked up real bad—that you must be nothing but a fuckup.”

He wasn’t always this way, but his life was hard from the beginning. Jeff spent his early years fearing his mother would kill him. She suffered from delusions and was shuffled in and out of mental health facilities. Sometimes she was violent, hurling insults and threatening her family with knives.

Jeff’s father, though, was his hero. He was a garbage collector—”the best in the city”—and Jeff followed in his footsteps: “I became a garbage collector too. I worked and paid taxes for 12 years. But one day I was caught with a tiny bit of pot in my urine and was fired on the spot.”

It was devastating. Jeff fell into a deep depression. He started using crack, and later heroin. Soon, he had burned through his money, lost his apartment, and was abandoned by his fiancé. “Being a garbage man was everything to me. When I lost that, I lost everything.”

Jeff’s is one of the many stories of homelessness chronicled in Robert Okin‘s new book Silent Voices. As a psychiatrist who has served as the Commissioner at the Department of Mental Health in both Massachusetts and Vermont, a professor emeritus at the University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine, and former Chief of Service in the San Francisco General Hospital’s Department of Psychiatry, Okin has worked with homeless patients throughout his career.

Still, as he passed them daily on the streets of the city where he lived and worked, he began to wonder about who they really were. How did they cope with their stresses, what did they think about, and how did they make it through the cold, foggy San Francisco nights? “I understood their lives from a clinical point of view. I didn’t really get it from a humanistic point of view,” Okin told me. “I wanted to know about the details.”

So, he started asking. He would broach conversations on street corners, inquiring about street people’s pasts, survival strategies, and inner lives. “Behind the rags and the carts and the strange behaviors—behind the stigma of poverty and mental illness—are human beings with a lot of the same hopes and feelings, joys, frustrations that the rest of us have,” he says. “I wanted to help readers see that, when they pass someone on the street who is sleeping, they should try to remember: That person has a story.”

In the book, Okin pairs photographic portraits with extended quotes from his subjects, offering context only when needed. He’d rather let his readers experience the stories as he did. Not surprisingly, they are full of hardship, grief, and regret. “Many believed that they were at fault for their own predicaments,” Okin says. “Even when you heard the stories that these people had—abused, neglected. Many of them just never had a chance.”

Drug addiction is a common theme. People started using for a variety of reasons, especially those who experienced neglect or abuse. Once they landed on the streets, they were caught in a perpetual cycle. Addictions are particularly hard to break when you don’t have a roof over your head, Okin says. As one subject puts it, “Living on the street is so bad, you have to be either stoned or crazy to bear it.”

Mental illness was also common, but there was often an associated history of childhood trauma, abandonment, and mistreatment. Many of the mentally ill women he encountered had been sexually abused or exploited as children.

Just hearing the stories took a toll on Okin. “I would come home the end of the day, sometimes feeling connected and exhilarated, but often feeling sad, with a lump in my throat,” he says. “It really touched me deeply. There were many times when I just felt I couldn’t go out the next day. It was too sad, too demoralizing.”

What kept him going, he says, is the thought that sharing the stories might inspire others to take on the issue of homelessness. Given the right programs, he knew that many of his subject could pull themselves out of the abyss. “You need to get people into housing first, and then they are much more likely to get off drugs, get a job, or in other ways pull themselves together. They are able to function much more constructively if they don’t have to fight for survival.”

Indeed, “housing first” programs are being implemented across the country. They pair chronically homeless people with subsidized long-term housing and in-house social services. The strategy has proved successful, not just in getting thousands of homeless off the streets, but in helping them rebuild their lives. It sounds expensive, but in fact it’s cheaper than band-aid approaches, which are laced with costs for hospital stays and incarceration.

Utah’s highly successful program, the subject of the cover story in our March/April print edition, is close to ending chronic homelessness in that state. “This problem can be solved in San Francisco just like it can be solved in Utah,” Okin told me. “The fact that there are now some successes will remove the argument that this is unsolvable. It will give states and the people in charge of budgets the comfort that they need—but ultimately the people in this city must demand the political will from their elected officials.” (Also read: “Just How Does a City Count Its Homeless? I Tagged Along To Find Out.“)

Jeff is one of the lucky ones. After being homeless for a decade he landed in a drug treatment program, and it may have saved his life. While living on the streets he suffered an infection that left abscesses all over his body: “They wouldn’t heal while I was on the street, even with antibiotics. Too much stress, too much exposure to bad weather, too many heroin injections.”

But, with the help of the program, he was placed in housing and assigned a social worker, who he says saw him every day for a year. Now he’s been clean for more than a year and landed a paid, part-time job with the program that assisted him. He also volunteers at an animal shelter, and has even adopted a kitten. “She’s my best friend. I’ve also started to think about what else I want to do with my life. Maybe I’ll live ’til 50.”