Abortion rights supporters jostle with protesters at the Texas state capitol in 2013.Tamir Kalifa/AP

The last time Texas lawmakers met in the state capitol, it was to pass the mammoth anti-abortion bill that was the target of state Sen. Wendy Davis’ all-night filibuster. Now the Legislature is in session again after a year-and-a-half-long recess, and conservatives are pushing a slew of new measures that would make it harder for women to end pregnancies.

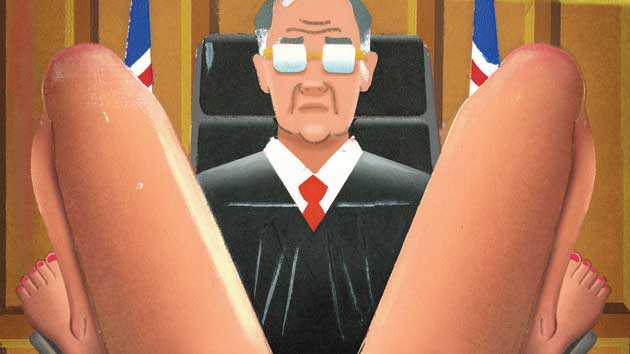

Two of these bills would publicize the names of judges who give minors permission to obtain abortions—a step that critics say would put judges under intense pressure, or even jeopardize their safety.

In 38 states, it is illegal for a minor to terminate a pregnancy without one parent’s knowledge. (Some of those 38 states go further, and require a parent’s permission.) Girls who are afraid or unable to involve their parents can ask a judge for permission instead. This confidential process, which the Supreme Court helped establish in the late ’70s and early ’80s, is called judicial bypass.

Since 2010, when Republicans captured a record number of legislative bodies and governors’ seats, lawmakers in several states have passed laws that limit the counties where a minor can petition for bypass or forbid anyone other than lawyers or court staff—such as an aunt or a teacher—from helping a young woman obtain one. And Alabama has approved a harsh new measure—blocked in court—that requires district attorneys to cross-examine minors who want to get abortions.

But Texas is the first state in recent memory to consider naming the judges who rule on bypass cases. One bill, introduced by Republican Rep. Ron Simmons, would name the judges outright. Another proposal, authored by fellow Republican Rep. Geanie Morrison, would list the courts that grant bypass petitions. Since some courts have just a few judges, Morrison’s bill would make it easier for abortion foes to identify and pressure judges who give minors permission to get abortions. Morrison did not respond to requests for comment, and Simmons declined to comment.

Proponents of the bills have argued that they would bring accountability to the bypass process. Critics say that the bills are aimed at discouraging judges from participating in bypass hearings. “This isn’t about transparency in the petition process. It’s about punishing judges,” warns Susan Hays, a Texas attorney who works with a nonprofit group called Jane’s Due Process to represent minors in bypass cases. Texas, she notes, elects its judges. “We pass these bills, and suddenly you don’t even have this option in huge swaths of the state.”

Several thousand minors have abortions in Texas each year. But few of them use the bypass process.

Many of the young women who use the bypass system have been physically abused by a parent or have a mother or father who threatened to kick them out of the house if they ever got pregnant. Some are caretakers for their parents. Others are estranged from them: “Mom’s dead, Dad’s in prison, they never liked me much anyway,” is how Hays, the attorney, has described these cases.

But if the state were to start naming judges, many would become unwilling to participate in the process, Hays argues. “Some of these courthouses already refuse to hear the girls’ petitions, which is eight shades of illegal, but what are we going to do about it?” she says. “Now, if it’s going to be public which judges are doing these, you’re going to have girls with nowhere to go.”

Texas Republicans have tried before to out the judges who make these sensitive rulings. In 2005, Republican Rep. Phil King introduced a bill that would have not only publicized judges’ names and rulings, but also would have altered the law to make transcripts of the hearings available to the public. Opponents of the bill objected, noting that bypass hearing transcripts often contain enough information about a minor, such as the name of her school and a description of her home life, to make her identifiable to people who know her.

But one opponent of the bill was also concerned about the safety of the judges: Craig Enoch, a former Texas Supreme Court justice and a lifelong Republican, warned the Legislature that naming judges could place them and their families in danger from violent parents or extreme anti-abortion groups.

“I fully understand that difficult decisions is what judging is all about,” Enoch said in an interview with NOW on PBS. “My particular concern though, in the family law context, is where emotions run extremely high. And in this issue, on consent for an abortion, where emotions run even higher, that there is a concern I had for literally the physical safety of the judge.”

Enoch noted that when he served on the Texas Court of Appeals, a courtroom shooter injured two of his colleagues and killed a lawyer. “In the middle of this war,” he said, “why would someone think it interesting or important to say, we want to put on the internet the name of the judge and the decision the judge makes?”

King’s 2005 bill was ultimately derailed by a procedural error. Texans who oppose naming judges who grant bypass requests may not be so lucky this time around.