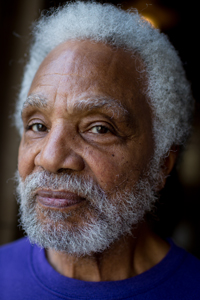

Nebraska state Sen. Bob Hilkemann of Omaha, the key swing vote, is thanked by a death penalty opponent.Mary Anne Andrei

When the final aye of the roll call vote was recorded on the electronic panel above the West Chamber of the Nebraska State Capitol in Lincoln yesterday, the crowd in the galleries overlooking the floor couldn’t contain their shouts of relief. Or maybe it was disbelief. The wooden benches were filled with death penalty opponents who had come hoping to see the senators of the unicameral Legislature override Gov. Pete Ricketts’ veto of a bill repealing the state’s death penalty law—but they had good reason to worry they no longer had the necessary votes. After enduring more than two hours of heated debate (ranging from tearful stories of personal evolution to bellowed passages from the Bible), the override received exactly the 30 votes required. The death penalty was officially abolished in Nebraska, and activists whooped and clapped, prompting gavel-pounding and calls for order.

Repeal of the death penalty has been championed by liberals in the Legislature since 1973. Sen. Ernie Chambers of Omaha, who sponsored this year’s effort, has tried to repeal the death penalty 36 previous times in his four decades as a Nebraska legislator. He secured passage in 1979 but didn’t have enough votes to override Gov. Charles Thone’s veto. In 1992, the repeal was introduced with 25 cosponsors, but support unraveled before a floor vote. Yet, ironically, what made yesterday’s successful override possible was not Chambers himself but rather a new class of 18 first-year senators, who arrived all at once because of term limits originally passed in an effort to ouster Chambers. “I wish that I could say that it was my brilliance that brought us to this point,” he said in opening debate on the bill, “but this would not be true, and we all know it. Had not the conservative faction decided it was time for a change, there’s no way that what is happening today would be happening today.”

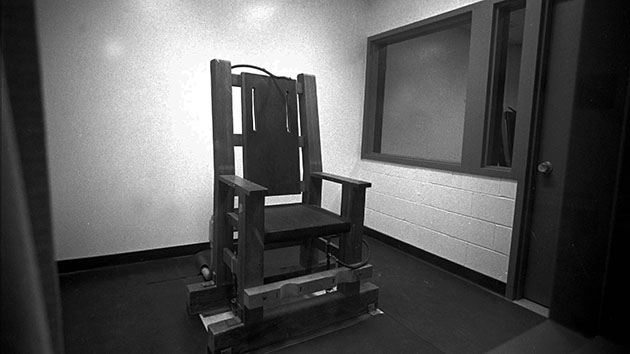

This new group of conservatives were won over to Chambers’ viewpoint by a variety of factors—the cost of pursuing death penalty cases in a state that has executed just three death row inmates since 1959; very public scandals surrounding recent failures in the state penal system; suspicions about handing the ultimate authority over to any governmental agency; and a significant push by the Archdiocese of Omaha, with backing from the Vatican, to outlaw the death penalty. Still, Ricketts, also newly elected in the fall, never expected such swift movement—and fought hard to block it. Just this month, when some state senators pointed out that Nebraska didn’t have the necessary drugs to carry out a lethal injection, the governor went so far as to acquire new drugs without legislative approval from a private company in India. When a major riot occurred at the state penitentiary facility in Tecumseh two weeks ago, where two inmates were killed, Ricketts organized a tour for senators to survey the damage and argued that the death penalty was necessary to suppress such uprisings.

Nevertheless, a little more than a week ago, the repeal of the death penalty (LB268) passed by a comfortable 32-15 majority. But then, a tragedy struck that seemed destined to derail the effort. Just hours after the bill went to the governor’s desk, Omaha police officer Kerrie Orozco, who had been delaying the start of her maternity leave until her premature baby could be discharged from the hospital, was shot dead on her final shift before she was scheduled to bring her daughter home. The shooting was near the Omaha districts represented by Chambers and Tanya Cook. News of the shooting brought issues of race to the surface (both Cook and Chambers are African American), especially after the governor called on constituents “to reach out to and talk to senators.” Phone messages and emails started flooding into the Capitol—including death threats. A social-media campaign was launched against senators who “chose Chambers” over their constituents. Ricketts said that he didn’t want to politicize Orozco’s death but held off on issuing his veto until his return from her funeral in Omaha on Tuesday, which drew thousands of mourners to the procession route.

Under such pressure, Sen. Jerry Johnson of Wahoo withdrew his support of the repeal. Going into yesterday’s session, both Sens. John Murante of Gretna and Robert Hilkemann of Omaha acknowledged that they were reconsidering their support for the repeal as well. If both flipped, the governor’s veto would be upheld. So as debate on the veto override proceeded on the floor, the chamber grew palpably tense when Murante announced, “I pledged to do my best to vote the way the majority of my constituents want, and it has become obvious to me that the majority support Governor Ricketts’ veto.” Everything would come down to Hilkemann’s vote. As senators continued to rise to speak for another hour, the lobbying of Hilkemann by both sides grew so intense that he left the floor. (Two citizens who were standing in the hallway reported seeing representatives from the governor’s office shouting at him before the final vote.) After Hilkemann finally decided to continue his support for the repeal, sealing the 30-19 victory, death penalty activists rushed to the chamber door to embrace him and shake his hand. He smiled broadly but insisted that he didn’t deserve any special recognition. “We were all number 30,” he said.

Within a matter of hours, the editorial board of the New York Times was ballyhooing the vote as a bipartisan acknowledgment, even “in the deep-red heart of America,” that “capital punishment is an abhorrent and indefensible practice.” But even as opponents of the death penalty are celebrating around the country, Sen. Beau McCoy of Omaha has announced the creation of Nebraskans for Justice, a new group dedicated to putting the death penalty on the ballot measure. If he can get signatures from 10 percent of registered voters by the end of August, implementation of the law will be halted pending the outcome of the popular vote. So while the events of yesterday were stunning, especially to those of us who live in Nebraska, the future of the death penalty in the state—and the fate of the 10 men left on our death row—is far from certain.