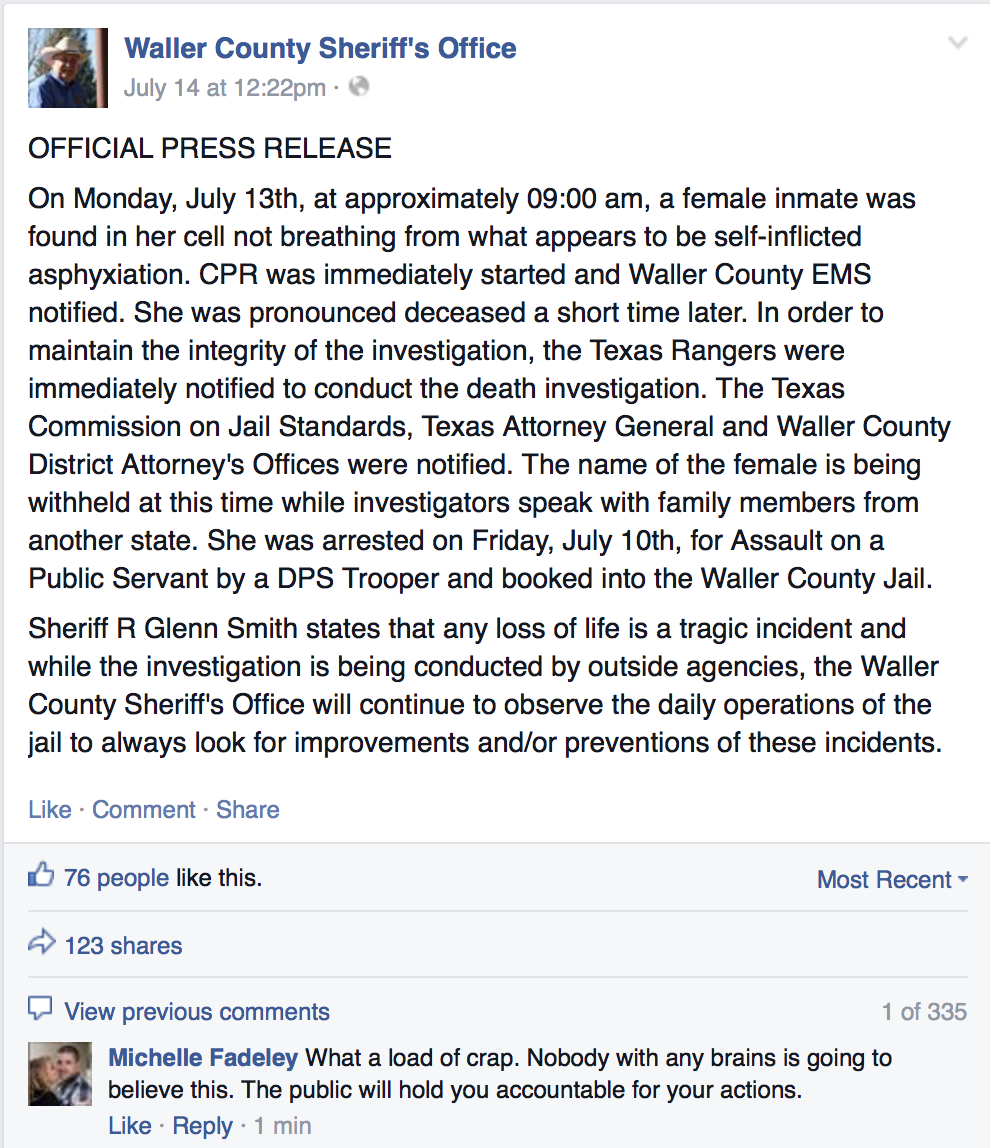

Around 9 a.m. on Monday, Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old from Illinois, was found not breathing in a Waller County, Texas jail cell, where she was declared dead shortly thereafter. At a press conference on Thursday evening, Waller County officials said that while the investigation is ongoing, preliminary evidence showed Bland had hung herself using a plastic bag that lined a trash can in her cell, and that prior to her death she had asked to use the phone to call her family. Over the weekend in jail, Bland had been in contact with family members to try and post bail, county officials said. The news of Bland’s death, which the county sheriff’s office attributed to “self-inflicted asphyxiation,” has raised questions about how a woman who’d been driving through the area to start a new job wound up dying in custody, as well as suspicions about foul play.

Bland, who friends described as an outspoken critic of police brutality, was booked into the jail three days earlier, after getting pulled over in Prairie View by a state Department of Public Safety trooper. The trooper claimed that Bland was uncooperative and that she kicked him, at which point he arrested her for “assault on a public servant,” the Houston Chronicle reported, citing a DPS spokesperson. A bystander’s video purporting to capture the arrest, first posted by the an ABC affiliate in Chicago, shows a trooper holding a woman down as she shouts “You just slammed my head into the ground. Do you not even care about that? I can’t even hear!”

Following her death, Bland’s family members and supporters have spread her story on social media, organized protests, and petitioned for the US Department of Justice to investigate the case. One friend told reporters that Bland was “strong mentally and spiritually” and that she would not have taken her own life. On Thursday, Waller County District Attorney Elton Mathis said investigators would review any evidence of stress that may have contributed to Bland’s death, including a video she posted in March, in which Bland says she is suffering from “a little bit of depression” and PTSD.

Whether or not it was suicide, Bland’s death comes amid an ongoing national conversation about race and criminal justice in America, and casts a spotlight on a county apparently rife with racial tensions. In 2007, Waller County Sheriff R. Glenn Smith was suspended—and eventually fired by city council members—while serving as police chief in Hempstead, a city in Waller County, following accusations of racism by community members. Less than a year after his firing, Smith was elected county sheriff. When asked about the accusations on Thursday, Smith said his firing in 2007 was “political,” and denied that he was a racist.

The history of Waller County’s racial tensions doesn’t end there. In 2003, the Houston Chronicle reported that two prominent black county officials, DeWayne Charleston and Keith Woods, claimed they were the target of an investigation by the county’s chief prosecutor because of their race. Charleston had been accused of keeping erratic hours and falsifying an employee time-sheet record, according to the Houston Chronicle. Charleston and Woods claimed the Concerned Citizens of Waller County was behind those accusations, and said that the group was conducting a Ku Klux Klan-like campaign against black officials:

Charleston, the county’s first black judge, said a county grand jury has interviewed him, although he declined to elaborate. And Woods, the four-term mayor of Brookshire, is facing questions about his role in the last city election.

“I do believe race plays a big part in what DeWayne and I are facing,” Woods said. “I feel that way because we’re the ones obviously not being given the benefit of the doubt (when) we face contrary decisions by the district attorney.”

Kitzman, 69, a retired state district judge, denies any racist implications in his interest in the two men. He says he’s simply doing his job by looking into complaints brought to him by residents.

Houston Chronicle reporter Leah Binkovitz also pointed out that a disproportionately high number of lynchings have been recorded in Waller County. According to the advocacy group Equal Justice Initiative, the county saw 15 lynchings of African Americans between 1877 and 1950.

.@byjoelanderson re: Waller county’s “tolerance,” from @eji_org‘s lynching report, disproportionately high numbers pic.twitter.com/7laXjGL03O

— Leah Binkovitz (@leahbink) July 16, 2015

Bland’s death has also raised questions about conditions at the Waller County jail, where in 2012, a 29-year-old white inmate named James Harper Howell IV, hung himself with the bed sheets in his cell. When asked about the 2012 death on Thursday, Smith responded that his staff had been monitoring inmates but that “these incidents occur in jails.”