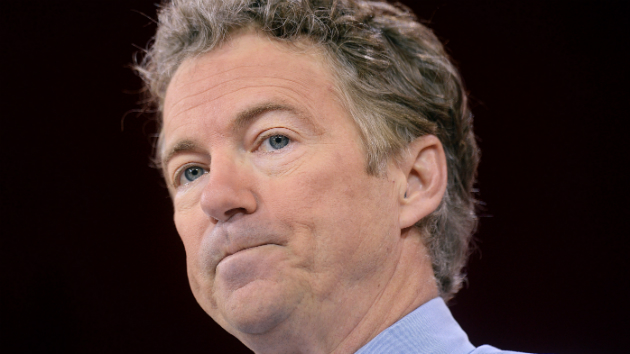

David Becker/ZUMA; Roman Pyshchyk/Shutterstock

The three Rand Paul aides who were indicted earlier this month are doing their best to turn the government case against them into an example of government overreach, and Google has taken their side in the fight.

In the summer of 2014, federal investigators began probing whether Ron Paul’s 2012 presidential campaign had paid Iowa state Sen. Kent Sorenson for his endorsement. After Sorenson confessed, investigators focused on three other men, including current presidential candidate Rand Paul’s nephew-in-law, Jesse Benton, whose email account supposedly contained evidence.

After a brief skirmish with Benton’s attorney about accessing Benton’s emails, FBI agents got a search warrant that entitled them to read the emails without Benton’s cooperation. But the plan did not go smoothly. Benton has a Gmail account, and Google’s policy is to notify users when their accounts have been hit with a search warrant. Benton’s attorney, Roscoe Howard, promptly filed a motion to block the search warrant, alleging that it was improper, and Google stopped cooperating with the FBI.

That was almost a year ago. Two weeks ago, Benton and two other top Paul aides, John F. Tate and Dimitri Kesari, were indicted on federal charges, including conspiracy, campaign finance violations, and making false statements. Prosecutors accused the men of paying Sorenson more than $73,000, hiding the payments by funneling them through a third party, and lying on campaign finance filings to cover them up.

The FBI still hasn’t gotten ahold of Benton’s emails. Last week, a judge ruled that the FBI had a right to the emails, but once again, Benton resisted and Google agreed.

“Frighteningly, the government still maintains that it has the right to trample Mr. Benton’s privacy rights and look through every single one of Mr. Benton’s emails, just as if his email account were a warehouse full of documents,” Howard wrote. “The government’s statement underscores its true intent—to conduct a fishing expedition.”

The government has now demanded that Google be held in contempt if the company doesn’t immediately turn over the emails, and it has argued that Benton and his attorney can raise their concerns at trial if they don’t like the way the search warrant was obtained. Most people don’t learn they’re the target of a search warrant until it has already been executed, which means they don’t have the opportunity to challenge the warrant until the evidence appears in court. But accessing emails is not like kicking down a door and finding a gun: Google controls access to the emails on its server, so the company’s refusal to comply with the FBI—and its willingness to tell Benton about the warrant—not only changes the dynamic in this particular case; it could also create a precedent for others.

Hanni Fakhoury, a senior staff counsel with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, said courts have not yet settled the question of how specific or broad email search warrants should be, and this case is one of the most prominent illustrations of how users can fight back.

“This case is smack in the middle of the debate,” Fakhoury says. “This is a very high-profile and dramatic example of it, because we’re talking about half a million emails.”

Howard, Benton’s attorney, wrote in one filing that his client had cooperated fully with investigators and provided a 50,000-page list of all the emails in his account, which may contain as many as 500,000 emails. Howard argues that the government’s search warrant is simply too broad, and that Benton’s Gmail account contains both personal and political correspondence.

Google has now officially joined the fight. Its lawyer, Guy Cook, told the court that the company will not turn over Benton’s emails.

“Google cannot be held in contempt simply for allowing Mr. Benton to exercise his appellate rights and awaiting the district court’s ruling on the warrant’s validity,” Cook wrote. The company’s position is that it will release emails only after the conflict over the search warrant has been resolved in court.

A Google spokeswoman declined to discuss the case specifically but said the company won’t comply with overly broad requests.

“When we receive a subpoena or court order, we check to see if it meets both the letter and the spirit of the law before complying,” she said. “And if it doesn’t, we can object or ask that the request is narrowed. We have a track record of advocating on behalf of our users.”

Fakhoury says Twitter and Facebook in the past have also notified their users about search warrants on their accounts, but that companies have become bolder in recent years.

“What’s changed post-Snowden is that they are more outspoken about it, and they’re more willing to interject more directly in situations,” he says. If companies don’t cooperate with the government, as in Google’s case, they may be held in contempt; if they cooperate and the warrant later turns out to be invalid, they would face no legal penalty. But their clients—people with social media or email accounts—want protection if a search warrant is issued. Companies “go out on a limb like this because it’s a good business practice for them, to look like they stick up for users,” Fakhoury notes.

The fight over Benton’s emails was kept secret for much of the past year, but it became public after the recent indictments. Benton’s attorney welcomed the increase in publicity, if only to attract attention to the battle. “This Court should unseal this matter so that the other Defendants can be a part of this discussion and so that the public can be aware of the government’s tactics,” he wrote last week.

Howard’s legal filings are littered with references to the government’s intrusive desire to “trample” Benton’s rights. That may be part of a strategy to claim that the government is bullying political opponents—a potentially potent argument in the libertarian sphere of Rand Paul supporters where Benton and his codefendants have made their living.

A hearing on whether Google must turn over the emails or wait for an appeal is scheduled for August 24.