Inmates rights advocates gather at the Capitol in Sacramento, CaliforniaRich Pedroncelli/AP

On Tuesday, 10 California inmates succeeded in stopping the decades-long use of indefinite solitary confinement in the state’s prison system. In a landmark settlement to a class-action suit they filed in 2012, California must now institute widespread reforms—which advocates hope will be a catalyst for change across the nation.

As part of the settlement, prison officials can isolate an inmate only if he or she commits a serious or violent infraction. Any perceived rule violation must be then proven in a hearing. Even those who do end up housed in the so-called Secure Housing Unit (SHU) will have different living quarters. The “high-security but nonisolation environment” will allow prisoners movement without restraints, the same amount of time away from their cells as the general prison population, access to educational and recreational programs, and physical contact with their visitors.

The settlement also bars the prison from housing inmates in these units for more than 10 years and will officially put an end to indeterminate stays. Instead, there will be a two-year program that provides incremental steps with increasing privileges to return to the general population.

Most inmates currently serving time in solitary are expected to qualify for removal under the settlement agreement—including all who have served more than 10 years—and they will be transitioned out over the next year.

“It is a remarkable feat of political organizing. This whole movement and the result is because of their collective action,” said Alexis Agathocleous, counsel on the suit and the deputy legal director at the Center for Constitutional Rights. “It’s a huge step forward, in terms of how solitary confinement is used in California, but I really think it also sets up the model for how reform can occur around the country.”

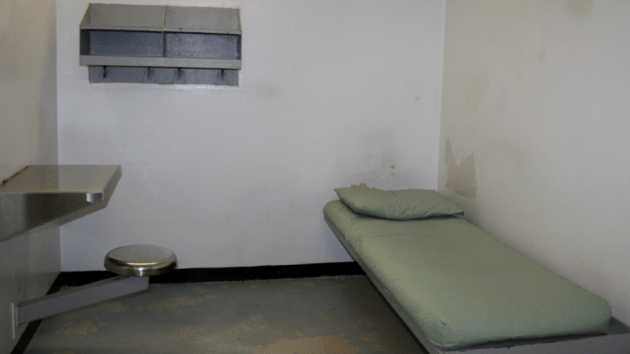

As my colleague Shane Bauer wrote in an award-winning 2012 feature, thousands of inmates idle alone inside small concrete cells within the Security Housing Unit at California’s notorious Pelican Bay State Prison. Confined to the windowless rooms for 22.5 hours a day, prisoners in solitary are allowed only a short daily reprieve from their cells for exercise, inside another small cement room that is equipped with a camera to monitor their activities.

Gabriel Reyes spent more than 17 years living this way, without access to direct sunlight, physical contact with another person, rehabilitation and education programs, and even phone calls from his family. “Unless you have lived it, you cannot imagine what it feels like to be by yourself,” he wrote in 2011, “between four cold walls, with little concept of time, no one to confide in, and only a pillow for comfort—for years on end. It is a living tomb.”

Reyes ended up at Pelican Bay after burglarizing an empty house in 1995. It was his third conviction, and, under California’s “three strikes” law, it landed him 25 years to life. But it wasn’t this crime—or any other—that got him thrown into the SHU. Like many of the more than 1,100 prisoners housed there, Reyes was put in solitary simply for being suspected of being part of a gang.

Using the “Predictive Behavior Model,” prison officials could isolate inmates for just about anything they thought showed signs of gang involvement: associating with the wrong person, having certain kinds of tattoos, or even reading books and poetry that officials deemed suspect was enough to land a prisoner “in the hole.” And, at Pelican Bay, you could stay there for the rest of your life.

Researchers have documented the devastating and permanent mental- and physical health detriments caused by isolation, and, according to a 2013 Government Accountability Office report, there’s no evidence that the use of solitary confinement makes prisons safer. Still, around 80,000 inmates are currently housed in solitary units around the country, costing tax payers in the process: Pelican Bay spends an additional $12,300 per inmate per year.

Reyes has been fighting to change the system for years, along with many other inmates who have endured long stints in the SHU. After coordinating by talking through pipes or yelling from cell to cell, he and nine other inmates—who have each spent more than a decade in solitary—launched two hunger strikes and were eventually joined by more than 12,000 inmates across California.

Finally, in 2012, with the help of a legal team that included support from the Center for Constitutional Rights and California Prison Focus, the group of inmates decided to take legislative action—and now indefinite solitary confinement may be done with for good.

The prisoners themselves, including many of those whose suit brought about this settlement, will now be able to oversee its implementation. As inmate representatives they will also regularly meet with California prison officials to offer insights into prison conditions and programs.

While this settlement is a huge win in the fight to put an end to solitary confinement, advocates emphasize the battle is not over.

“It is a really big deal—and something that we hope will act as a tipping point,” said attorney Charles Carbone, co-counsel on the suit. “I am hoping what we did here in California not only cures the issue of solitary confinement and the practice of isolating prisoners, but also starts or leads a larger conversation about the prison epidemic.”