In early 2012, on a visit to San Francisco, Shannon Liss-Riordan went to a restaurant with some friends. Over dinner, one of her companions began to describe a new car-hailing app that had taken Silicon Valley by storm. “Have you seen this?” he asked, tapping Uber on his phone. “It’s changed my life.”

Liss-Riordan glanced at the little black cars snaking around on his screen. “He looked up at me and he knew what I was thinking,” she remembers. After all, four years earlier she had been christened “an avenging angel for workers” by the Boston Globe. “He said, ‘Don’t you dare. Do not put them out of business.'” But Liss-Riordan, a labor lawyer who has spent her career successfully fighting behemoths such as FedEx, American Airlines, and Starbucks on behalf of their workers, was way ahead of him. When she saw cars, she thought of drivers. And a lawsuit waiting to happen.

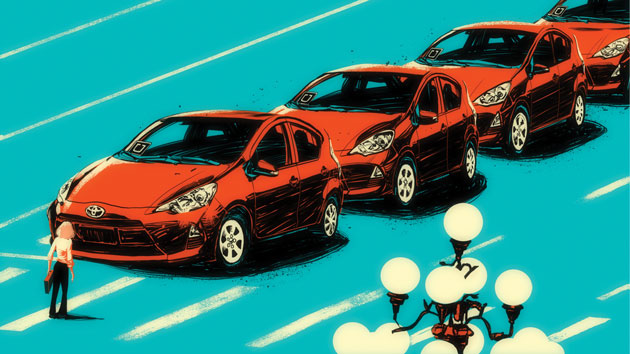

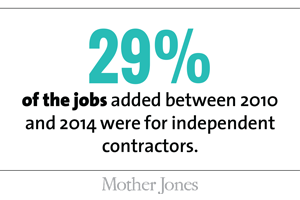

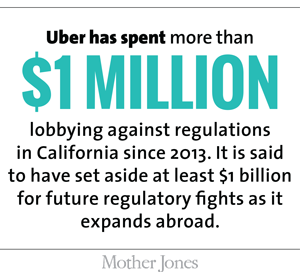

Four years later, Liss-Riordan is spearheading class-action lawsuits against Uber, Lyft, and nine other apps that provide on-demand services, shaking the pillars of Silicon Valley’s much-hyped sharing economy. In particular, she is challenging how these companies classify their workers. If she can convince judges that these so-called micro-entrepreneurs are in fact employees and not independent contractors, she could do serious damage to a very successful business model—Uber alone was recently valued at $51 billion—which relies on cheap labor and a creative reading of labor laws. She has made some progress in her work for drivers. Just this month, after Uber tried several tactics to shrink the class, she won a key legal victory when a judge in San Francisco found that more than 100,000 drivers can join her class action.

“These companies save massively by shifting many costs of running a business to the workers, profiting off the backs of their workers,” Liss-Riordan says with calm intensity as she sits in her Boston office, which is peppered with framed posters of Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren. The bustling block below is home to two coffee chains that Liss-Riordan has sued. If the Uber case succeeds, she tells me, “maybe that will make companies think twice about steamrolling over laws.”

After graduating from Harvard Law School in 1996, Liss-Riordan was working at a boutique labor law firm when she got a call from a waiter at a fancy Boston restaurant. He complained that his manager was keeping a portion of his tips and wondered if that was legal. Armed with a decades-old Massachusetts labor statute she had unearthed, Liss-Riordan helped him take his employer to court—and won. “This whole industry was ignoring this law,” Liss-Riordan recalls. Pretty quickly, she became the go-to expert for employees seeking to recover skimmed tips. And before she knew it, her “whole practice was representing waitstaff.”

In November 2012, she won a $14.1 million judgment for Starbucks baristas in Massachusetts. After a federal jury ordered American Airlines to pay $325,000 in lost tips to skycaps at Boston’s airport, one of the plaintiffs dubbed her “Sledgehammer Shannon.” When one of her suits caused a local pizzeria to go bankrupt, she bought it, raised wages, and renamed it The Just Crust.

Liss-Riordan estimates that she’s won or settled several hundred labor cases for bartenders, cashiers, truck drivers, and other workers in the rapidly expanding service economy. Lawyers around the country have sought her input in their labor lawsuits, including one that resulted in a $100 million payout to more than 120,000 Starbucks baristas in California. (The ruling was later overturned on appeal.) In a series of cases that began in 2005, she has won multimillion-dollar settlements for FedEx drivers who had been improperly treated as contractors and were expected to buy or lease their delivery trucks, as well as pay for their own gas.

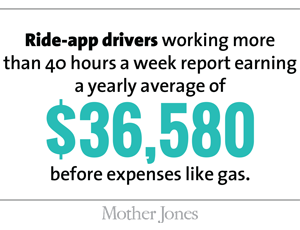

Her Uber offensive began in late 2012, when several Boston drivers approached her, alleging that the company was keeping as much as half of their tips, which is illegal under Massachusetts law. Liss-Riordan sued and won a settlement in their favor. But while looking more closely at Uber, she confirmed the suspicion that had popped up at that dinner in San Francisco: The company’s drivers are classified as independent contractors rather than official employees, meaning that Uber can forgo paying for benefits like workers’ compensation, unemployment, and Social Security. Uber can also avoid taking responsibility for drivers’ business expenses such as fuel, vehicle costs, car insurance, and maintenance.

In August 2013, Liss-Riordan filed a class-action lawsuit in a federal court in San Francisco, where Uber is based. Her argument hinged on California law, which classifies workers as employees if their tasks are central to a business and are substantially controlled by their employer. Under that principle, the lawsuit says, Uber drivers are clearly employees, not contractors. “Uber is in the business of providing car service to customers,” notes the complaint. “Without the drivers, Uber’s business would not exist.” The suit also alleges that Uber manipulates the prices of rides by telling customers that tips are included—but then keeps a chunk of the built-in tips rather than remitting them fully to drivers. The case calls for Uber to pay back its drivers for their lost tips and expenses, plus interest.

Uber jumped into gear, bringing on lawyer Ted Boutrous, who had successfully represented Walmart before the Supreme Court in the largest employment class action in US history. Uber tried to get the case thrown out, arguing that its business is technology, not transportation. The drivers, the company contended, were independent businesses, and the Uber app was simply a “lead generation platform” for connecting them with customers.

Techspeak aside, Liss-Riordan has heard all this before. When she litigated similar cases on behalf of cleaning workers, the cleaning companies claimed they were simply connecting broom-pushing “independent franchises” with customers. When she won several landmark cases brought by exotic dancers who had been misclassified as contractors, the strip clubs argued that they were “bars where you happen to have naked women dancing,” Liss-Riordan recounts with a wry smile. “The court said, ‘No. People come to your bar because of that entertainment. Adult entertainment. That’s your business.'”

Uber’s argument is pretty similar to that of the strip clubs. “Uber is obviously a car service,” she says, and to insist otherwise is “to deny the obvious.” An Uber spokesperson wouldn’t address that characterization, but said that drivers “love being their own boss” and “use Uber on their own terms: they control their use of the app, choosing when, how and where they drive.”

Some observers have suggested creating a new job category between employee and contractor. But Liss-Riordan is tired of hearing that labor laws should adapt to accommodate upstart tech companies, not the other way around: “Why should we tear apart laws that have been put in place over decades to help a $50 billion company like Uber at the expense of workers who are trying to pay their rent and feed their families?”

For the most part, courts have sided with her. Last March, a federal court in San Francisco denied Uber’s attempt to quash the lawsuit, calling the company’s reasoning “fatally flawed” (and even citing French philosopher Michel Foucault to make its point). In September, the same court handed Liss-Riordan and her clients a major victory by allowing the case to go forward as a class action. The judge in the Lyft case has called the company’s argument—nearly identical to Uber’s—”obviously wrong.” Last July, the cleaning startup HomeJoy shut down, implying that a worker classification lawsuit filed by Liss-Riordan was a key reason.

Meanwhile, other sharing-economy startups are changing the way they do business. The grocery app Instacart and the shipping app Shyp—Liss-Riordan has cases pending against both—have announced they will start converting contractors to full employees. Liss-Riordan says that’s her ultimate goal: to protect workers in the new economy, not to kill the innovation behind their jobs. “This is not going to put the Ubers of the world out of business,” she says.

One of her opponents has played a more creative offense. Last fall, the laundry-delivery app Washio convinced a judge that Liss-Riordan had no right to practice law in California. Liss-Riordan easily could have relied on a local lawyer to head the case, but instead she signed up to take the California bar exam in February. “Their plan kind of backfired,” she says. “I expect they’ll be seeing more of me, rather than less.”