<a href="http://www.shutterstock.com/pic-74735389/stock-photo-environmental-problem-plastic-trash-on-a-coral-reef-i-cleared-up-this-and-other-rubbish-from.html?src=6aIADFOPvhAWQ3zr60EY4Q-1-23">Rich Carey</a>/Shutterstock

Discarded plastic will outweigh fish in the world’s oceans by 2050, according to a report from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. That is, unless overfishing moves the date up sooner.

The study, a collaboration with the World Economic Forum, found that 32 percent of plastic packaging escapes waste collection systems, gets into waterways, and is eventually deposited in the oceans. That percentage is expected to increase in coming years, given that the fastest growth in plastic production is expected to occur in “high leakage” markets—developing countries where sanitation systems are often unreliable. The data used in the report comes from a review of more than 200 studies and interviews with 180 experts.

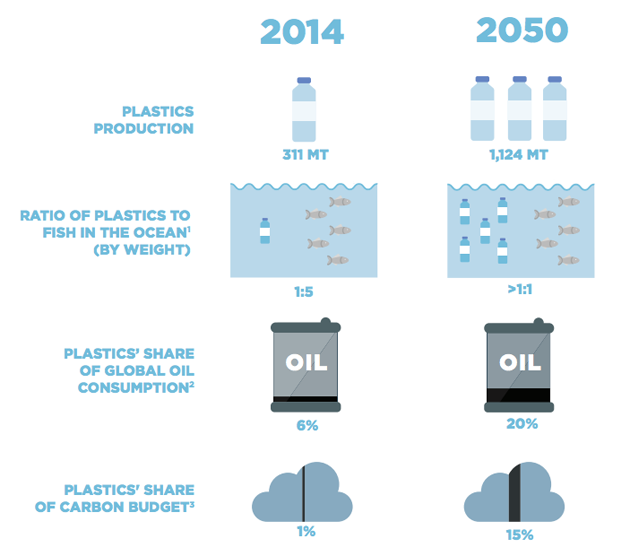

Since 1964, global plastic production has increased 20-fold—311 million tons were produced in 2014—and production is expected to triple again by 2050. A whopping 86 percent of plastic packaging is used just once, according to the report’s authors, representing $80 billion to $120 billion in lost value annually. That means not only more plastic waste, but more production-related oil consumption and carbon emissions if the industry doesn’t alter its ways.

The environmental impact of plastic waste is already staggering: For a paper published in October, scientists considered 186 seabird species and predicted that 90 percent of the birds—whose populations have declined by two-thirds since 1950—consume plastic. Plastic bags, which are surprisingly degradable in warmer ocean waters, release toxins that spread through the marine food chain—and perhaps all the way to our dinner tables.

Most of the ocean’s plastic, researchers say, takes the form of microplastics—trillions of beads, fibers, and fragments that average about 2 millimeters in diameter. They act as a kind of oceanic smog, clouding the waters and coating the sea floor, and look a lot like food to small marine organisms.

In December, President Barack Obama signed a law banning microbeads, tiny plastic exfoliaters found in toothpaste and skin products that get flushed into waterways. But the MacArthur report urges plastic producers to step up and address the problem by developing products that are reusable and easily recycled—and that are less toxic in nature—and working to make compostable plastics more affordable.

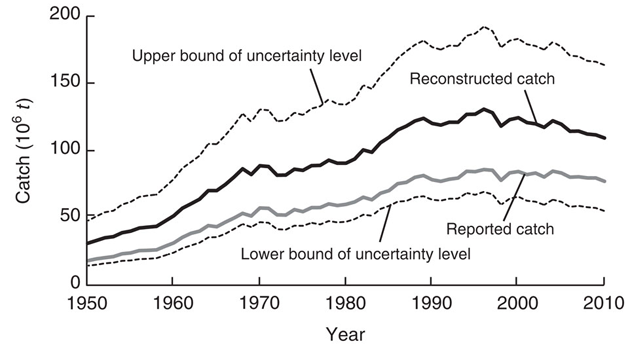

The 2050 prediction is based on the assumption that global fisheries will remain stable over the next three decades, but a report released last week suggests that may be wishful thinking. Revisiting fishery catch rates from the last 60 years, Daniel Pauly and Dirk Zeller of the University of British Columbia found that the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization drastically underestimates the amount of fish we pluck from the seas. The United Nations relies on official government data, which often only captures the activities of larger fishing operations. When the British Columbia researchers accounted for smaller fisheries, subsistence harvesting, and discarded catches, they calculated catches 53 percent larger than previously thought.

There was a glimmer of hope in the findings, though: The researchers write that fishing rates, after peaking in 1996, declined faster than previously thought—particularly among large-scale industrial fisheries. Whether that trend will hold is another story.